Ellsworth’s Cinema of Swords: Goofballs in Harem Pants

This week we’re looking at the spate of Arabian Nights fantasies that came out of Hollywood during World War II, when cinema audiences were looking for colorful distractions from the grim news of the war. And boy howdy, were these films ever colorful distractions, bizarre and often wacky in ways that seem incredible by current standards.

The example was set, not by Hollywood, but by the 1940 British production of The Thief of Bagdad, a serious fantasy film that established the whole genre. We’ll start with that and then introduce Hollywood’s increasingly strange variations on the theme. Hang on to your turbans!

The Thief of Bagdad

Rating: ****

Origin: UK, 1940

Directors: Ludwig Berger, Michael Powell, Tim Whelan

Source: Criterion Collection DVD

Everybody loves this movie. It’s got heart, magic, music, adventure, romance, and ambitious special effects that alternate between stupendous and hilarious. Hang it, even I love this movie. And yet, to be perfectly frank, it’s a bit of a mess.

Given its production history, it’s a wonder it was ever made at all. Hungarian-English producer Alexander Korda was determined to create a grand epic, a career-defining masterpiece, and inserted himself into every aspect of the film’s production, sometimes causing chaos. Shooting started in early 1939 with German director Ludwig Berger, but he wasn’t delivering a story on the scope that Korda wanted, and then that war thing happened, so Berger was replaced by three other directors, all English or American. Throughout production the film’s story was in flux, constantly changing, with new elements added and other parts cut. When war actually broke out in September 1939, further production in the U.K. was suspended, and the whole thing was picked up and moved to Hollywood, with side shooting in the Grand Canyon.

Whew! Somehow Korda took all these disparate assets and assembled a mostly coherent whole, but one can see the seams where he stitched it together in the film’s continuity lapses and sudden changes of tone. And yet, all that hardly matters, because this Arabian Nights fable is so vivid and fanciful that dream logic seems to hold it together.

Certainly the romance that’s ostensibly the plot’s driving wheel is flat and rather dull, as John Justin (King Ahmad) and June Duprez (Princess — that’s all the name she gets) don’t provide much heat, chemistry, or interest. Perhaps they knew they were hopelessly outclassed by the real stars: the young thief, the evil vizier, and the mighty djinni. In truth, this is their movie. The thief, Abu, is played with engaging panache by the fifteen-year-old Sabu (that’s all the name he gets), a lad of genuine charm from India. The great German actor Conrad Veidt is Jaffar — wizard, tyrant, lecher, and the archetypal wicked vizier — and he has a fine old time with the role. But no one has as much fun as the African American actor Rex Ingram as the Djinni, whose energy and gusto would make him seem 90 feet tall even if he wasn’t already being depicted as 90 feet tall.

The story is loosely based on Doug Fairbanks’s 1924 silent epic, with a half-dozen other familiar Arabian Nights elements tossed into the stew to keep things bubbling. There’s a flying carpet, magical curses and transformations, grotesque monsters, and voyages to unknown lands: picking up from its silent predecessor, this is the film that set the style and tone for all Arabian fantasy films to follow, up to and especially including Walt Disney’s Aladdin.

But be warned: the European colonialist gaze is strong here. There are people of all different skin shades in Bagdad, but lightness of color is the infallible guide to status. This is somewhat offset by the prominent casting of brown Sabu and Black Rex Ingram — but damn.

As for the film’s look, “sumptuous” doesn’t even begin to describe it. Visual wizard William Cameron Menzies, whose credits stretched back to the 1924 Thief of Bagdad, was Korda’s associate producer and uncredited fourth director, and his eye for form and color deserves much of the credit for its visual appeal. The excellent score is an early effort by Miklós Rósza, best known for his soundtrack for Ben-Hur (1959). There are some hokey songs — during part of the production cycle Korda thought he wanted the film to be a musical — but the orchestral pieces are dynamic and memorable.

Guilty pleasure: The picture’s screenwriter, Miles Malleson, gets to play the delightful part of the dotty old Sultan of Basra, who collects magical toys. I have to say, seeing the script guy having such fun warms my writer’s heart. And even C. Aubrey Smith would be envious of his amazing whiskers.

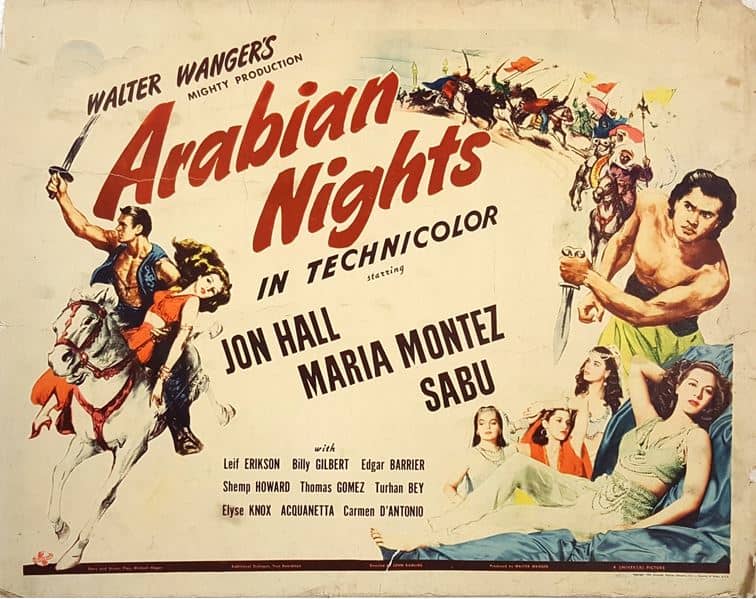

Arabian Nights

Rating: **

Origin: USA, 1942

Director: John Rawlins

Source: Universal Cinema Classics DVD

In the 1940s Universal was a modest-sized studio whose business was cranking out low-budget adventure pictures in every genre. After he starred in the 1940 British Thief of Bagdad, Indian teen star Sabu moved to Hollywood and signed a contract with Universal. They cast him in some jungle adventures but also decided to try him in their own Arabian Nights fantasy, titled, er, Arabian Nights. The studio splurged on fancy costumes, big sets, and shot it all in Technicolor, but relied on their usual stable of B- and C-list actors to round out the cast.

The movie’s title notwithstanding, it doesn’t seem like anyone involved with this story read The Arabian Nights’ Entertainment beyond the list of characters, cherry-picking the ones that sounded familiar. Haroun-al-Raschid (Jon Hall), Caliph of Bagdad, is betrayed by his Grand Vizier in favor of his evil half-brother, Kamar, who is determined to steal the throne because it’s the only way he can win the love of the ambitious dancing girl Sherazade (Maria Montez). Yeah, that’s how dumb this is. Sherazade is part of a troupe of “humorous” traveling entertainers that includes an acrobat, Ali (Sabu), a doofus named Aladdin whose shtick is always searching for his lost lamp, and another doofus who tells boring sea stories and goes by the name Sinbad played by Shemp Howard of the Three Stooges, wearing regrettable brownface.

So, the plot: Haroun, wounded in the vizier’s coup but saved by Ali and disguised, falls in with his troupe of entertainers; Haroun and Sherazade make eyes at each other, guards with scimitars appear, and gags and pursuits ensue. Evil Kamar openly wants the throne and the love of Sherazade; the evil vizier secretly wants the throne and the love of Sherazade; disguised caliph Haroun wants his throne back and … well, you get it. Despite the references to magic lamps, it’s a conventional dynastic struggle with no fantasy elements to it, unless you count the male fantasy in which Ali hides among the caliph’s scantily-clad harem women while two of them distract the eunuch guards with a hair-pulling cat-fight. (Yup.) We do get ornery camels and shiny turbans and scenic sand dunes, but the story doesn’t make a lick of sense, the acting is uniformly terrible, and all the scimitar-clashing fights are at the level of community-theater stage combat. So naturally it was a big hit, and henceforth Hollywood had a new ongoing adventure genre, the Arabian Fantasy! Allah preserve us.

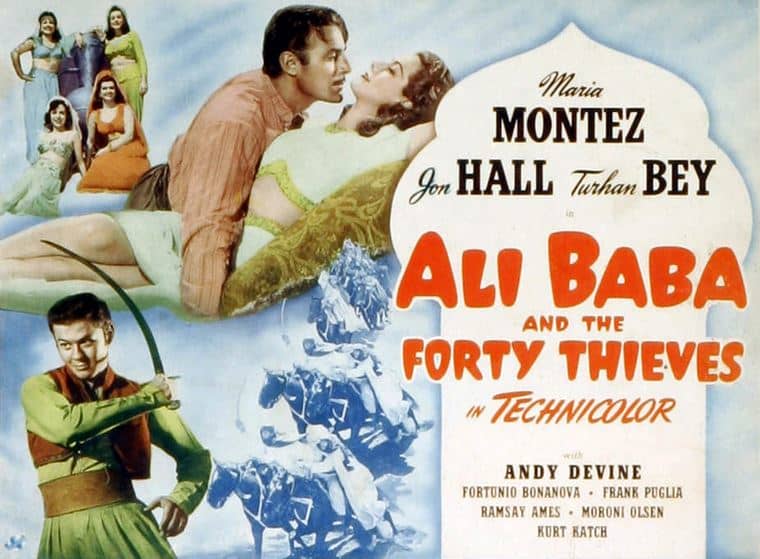

Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves

Rating: ***

Origin: USA, 1944

Director: Arthur Lubin

Source: Universal DVD

After the success of the dumb Arabian Nights, Universal decided to give the genre another go with substantially the same cast — and we’re glad they did, because the second movie is 100% less dumb than the first. It starts out with an actual historical event, the 1258 siege and sacking of Bagdad by the Mongols of Hulagu Khan, and scenes of the massacre of the Bagdadis immediately set this film’s more serious tone. The Caliph is betrayed by his Grand Vizier and killed in a Mongol ambush (note to self: if Sultan or Caliph, never have a Grand Vizier), but the Caliph’s only son, Ali, escapes. Though historically the boy was captured by the Khan, here he gets away into the desert where he stumbles upon the secret hideout of a band of forty thieves. And yes, the magic words “Open, sesame,” do open the lair’s stone doors, the only fantasy element in this film. To the bandits, Ali reveals his identity as the Caliph’s son, and their leader, Old Baba, adopts him as his own, hiding him under the new name Ali Baba. Old Baba appoints his aide, Abdullah — squeaky-voiced Andy Devine, best known for playing comic sidekicks in Westerns, here in more regrettable brownface — to be Ali’s guardian and also, inevitably, his comic sidekick.

Ten years pass, and Ali, now grown (and henceforth played by Jon Hall), emerges as the leader of the gang, which he’s re-forged into a band of freedom fighters conducting a guerilla war against the occupying Mongols, the theme that marks this as a true wartime movie. The Forty Thieves now wear red and blue uniform robes, and they even have a catchy theme song they sing while galloping across the desert! “We riiiiide… plundering sons, thundering sons, forty and one for all, and all for one.” Hmm, that part sounds familiar. Wait, so does the next part: “Robbing the rich, feeding the poor….” Okay, got it: the Forty Thieves are the Merrie Men.

The film has an actual plot: Robin Hood, I mean Ali, is scouting a Mongol camp when he meets Lady Amara (Maria Montez) swimming fetchingly in the water of the oasis. Amara, the daughter of the treacherous vizier, is on her way to Bagdad to be married to Hulagu Khan — but as a little girl she had been the boy Ali’s childhood sweetheart, so this marriage must be stopped!

Swashbuckling follows, with raids, abductions, and captures, in all of which Amara is aided by her loyal knife-throwing servant, young Jamiel (Turhan Bey, making an impression — the role had been written for Sabu, but having become a naturalized citizen, the teen star had joined the Army Air Force to serve as a tail gunner in B-24s). Ali decides the time has come for full-scale revolt against the Mongols, but he gets captured himself, and to save him the thieves have to get smuggled into the palace inside forty man-sized oil jars — the only other nod, besides the cave doors, to the original Ali Baba story in The Arabian Nights’ Entertainment. In the end the uprising rises up in the nick of time, and — spoiler! — Lady Amara doesn’t have to marry Hulagu Khan. Somehow, it all works.

A Thousand and One Nights

Rating: ***

Origin: USA, 1945

Director: Alfred E. Green

Source: Amazon Streaming Video

Now we get wacky. This is a tongue-in-cheek Arabian Nights fantasy that falls somewhere between send-up of and homage to The Thief of Bagdad, especially the 1940 version. Aladdin of Cathay (?), played by Cornel Wilde, is a vagabond street singer whom we first see crooning an ode to the desirability of a row of women for sale at a slave auction. This is tasteless by current standards, but it does serve to inform us that in this film, the role of women is strictly ornamental — with a notable exception which we’ll get to shortly. This singing Aladdin has a comic sidekick, a pickpocket named Abdullah played by Phil Silvers — yep, it’s Sgt. Bilko, black-framed glasses and all. Everyone calls him crazy because he says he was born 1200 years too soon, makes jokes about television and gin rummy, and tells the palace guards their turbans are “groovy.”

Some story happens: in a scene lifted right out of The Thief of Bagdad, mounted guards clear everyone from the street at the approach of a princess’s elaborate sedan chair because “No man may gaze upon her and live.” That, of course, makes Aladdin determined to see her — and one daring trespass and two songs later, the vagabond and the princess (Adele Jergens, strictly ornamental) have fallen in love. He serenades her in a palace garden that, like many of the sets, is a virtual duplicate of the one from the equivalent scene in Thief of Bagdad. In fact, the whole look of the film, the architecture, the props, the bright costumes against the pastel backgrounds, is practically a love letter to William Cameron Menzies.

Soon enough the guards are shouting “Seize him!”, and Aladdin and Abdullah are on the run. In a mystic cave they meet a mystic mage with a mystic crystal, who sends them after a mystic treasure guarded by a mystic giant — Rex Ingram himself, fifty feet tall and looking exactly as he did playing the Djinni in Thief of Bagdad, once again pursuing his puny prey and doing That Laugh. The treasure turns out to be a magic lamp (oh, right: Aladdin) that contains the best thing about this movie, a sassy red-headed genie played by Evelyn Keyes and named, er, “Babs.” Keyes, who is lively, clever, and ornamental into the bargain, effortlessly steals the rest of the picture, and no wicked vizier, sultan’s evil twin, or mystic mage can stand against her. All the bad jokes are worth it just to savor her performance.

Bonus: in the action-packed finale Cornel Wilde, who’d been an Olympic fencer in the 1930s, gets a chance to show us what he can do with a sword, and it’s quite impressive. Groovy, even.

Additional installments in the Cinema of Swords:

Olivia de Havilland — First Queen of the Swashbucklers

Goofballs in Harem Pants

Disney’s Early Swashbucklers

‘50s Vikings – Havoc in Horned Helms

Laughing Cavaliers

Charming and Dangerous: Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.

LAWRENCE ELLSWORTH is deep in his current mega-project, editing and translating new, contemporary English editions of all the works in Alexandre Dumas’s Musketeers Cycle. Three volumes are in print, with the fourth, Blood Royal, coming from Pegasus Books this fall. His website is Swashbucklingadventure.net.

Lawrence Ellsworth’s secret identity is game designer LAWRENCE SCHICK, who’s been designing role-playing games since the 1970s. He now lives in Dublin, Ireland, and is co-designing a new mobile RPG for the WarDucks game studio.

Thief of Bagdad is one of my all-time favorites, although I admit it’s taken me multiple viewings to actually put the story together — it begins somewhere in the middle, then circles back to the beginning.

My other favorite of the genre (and which of the two is REALLY my favorite varies from viewing to viewing) is 1947’s Sinbad the Sailor starring Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., who swashbuckles all over the place — never walk when you can leap dramatically into frame.

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0039826/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0

Surely The Road to Morocco belongs in here somewhere.

I read the novelization of the 1924 Douglas Fairbanks silent version a while back (by one Achmed Abdullah — his real name as far as I can tell, though possibly not his birth name, and based on the script by (I believe) Fairbanks himself in collaboration with Lotta Woods.) http://rrhorton.blogspot.com/2018/11/old-bestseller-review-thief-of-bagdad.html

That novelization is not great, but seeing the reputation of the two film versions, I decided I needed to see them. I still haven’t found the silent version, but I did watch Korda’s THIEF OF BAGDAD a few months ago, and I think Lawrence’s review is spot on. The central romance is of negligible interest, but the fun parts (the thief, the Sultan’s toys, etc.) are great fun, and the special effects are very impressive.

Rich, every now and then TCM shows the silent Thief.

There’s a brief review of the earlier version of “Thief of Bagdad” in a previous article I wrote about silent swashbucklers:

https://www.blackgate.com/2017/01/09/silent-screen-swashbucklers-part-1-of-2-zorro-makes-his-mark/

I have a copy of that Thief of Bagdad novelization with illustrations by P. Craig Russell, which are just as lovely as you’d expect.

Joe, do you have Russell’s graphic novel version of Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung? It’s one of the most jaw-dropping things you’ll ever see.

No, but now I think I need it.