A Salute to a Science Fiction Bookseller

|

|

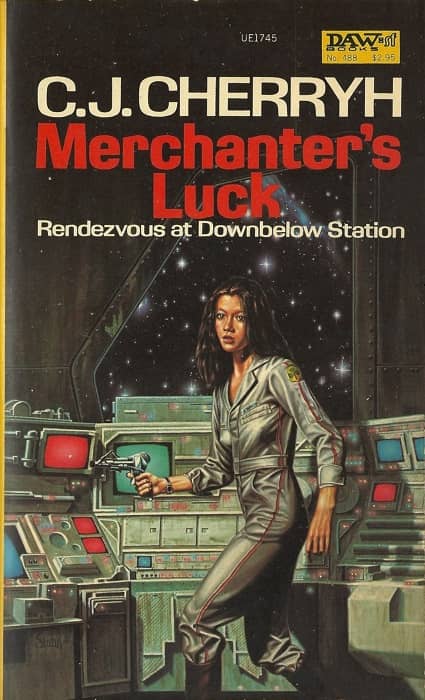

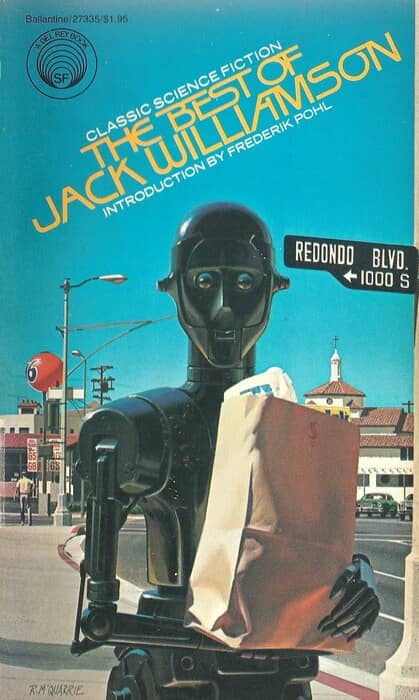

Infinite Dreams by John Haldeman (Avon 1979, cover by Clyde Caldwell),

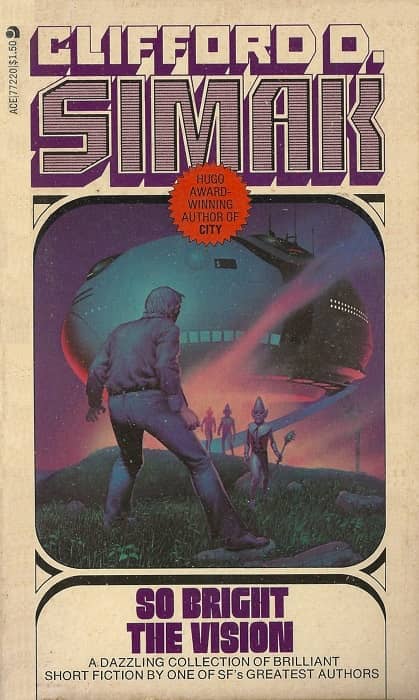

Chrysalis Volume 2, edited by Roy Torgeson (Zebra 1978, cover by Colin Hay)

Based on the email I get, a lot of Black Gate readers assume that I pull my Vintage Treasures out of the Cave of Wonders in my basement. It’s true that there’s a lot of paperback books down there (crammed up to the rafters in places), but the truth is that most of the books I choose to highlight in my regular Vintage Treasures column are recent acquisitions. I have a lot of regular sellers I trust, and one of them is North Dakota eBay seller pandoratim (Tim Friesen), whom I’ve purchased several titles from over the years (including Joe Haldeman’s first collection Infinite Dreams, which I talked about last year).

So I was a little dismayed to have my most recent purchase from Tim, Roy Torgeson’s 1978 anthology Chrysalis 2, canceled on Tuesday. In a cryptic message sent through eBay, Tim told me, “I am about to cancel your order because my health has deteriorated to the point where I can’t fulfill orders. I apologize for this poor handling of your order.” I wasn’t too concerned about the book, but I was concerned about a message like that from a trusted bookseller who’s sent me some fine volumes over the years. So I sent Tim this message.

Oh no! I’m so sorry to hear that. Don’t worry about the book at all. I appreciate you letting me know. I hope this is something you can recover from eventually. Readers need to stick together. I hope you’ll drop me a note letting me know you’re getting better. I’m at john@blackgate.com.

I was deeply saddened to get this response this morning.

Hi John, thanks a lot for writing. I’m sorry to say it’s not. I’ve gone into Palliative Care and likely have just a couple of weeks left. One of the great pleasures I gained from selling on eBay was getting to know repeat customers, like yourself. It’s one of my few regrets. However, it was my turn to draw the short straw, and I’m at peace with our decision. Best wishes to you going forward, John, please take care as you can during these crazy pandemic-filled and toxicly politicized days. It’s been a pleasure working with you,

sincerely,

Tim Friesen

There’s very little I can do for Tim, from three states away. But I can do this. In front of the collective community of Black Gate readers, I would like to thank Tim Friesen, for the great care he took with his books over the years, and the obvious joy he took in sharing them with so many others. In many ways I think that’s the highest calling a book lover can have — not simply to collect and preserve great books, but to do the real work of parting with them, and put them safely in other hands.

We salute you, Tim. Safe voyages from here.