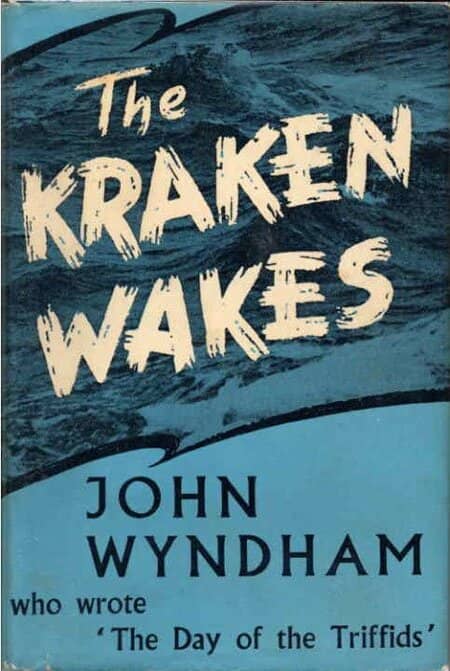

These Two Books Are Not the Same: John Wyndham’s The Kraken Wakes and Out of the Deeps

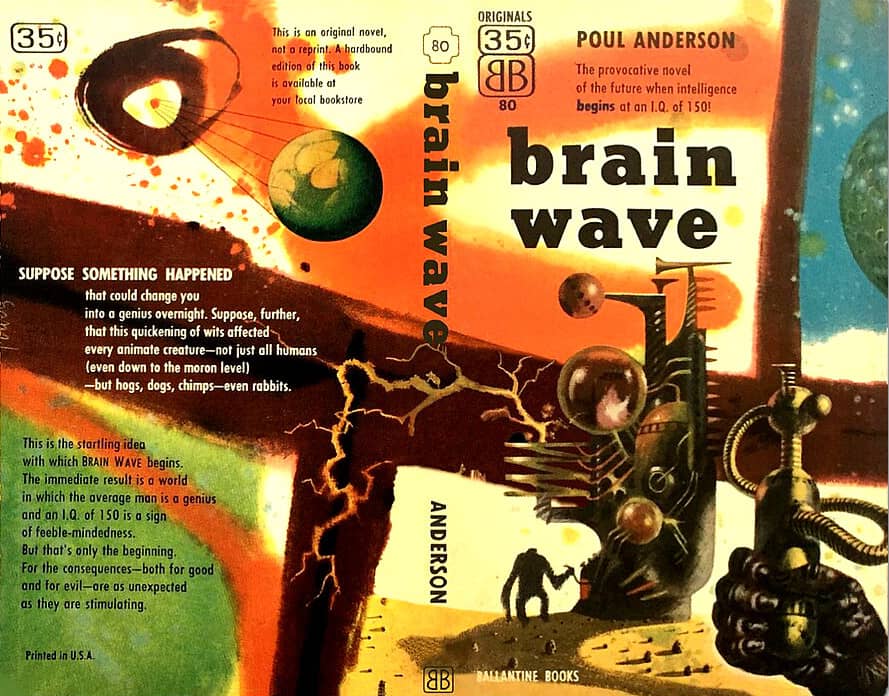

The Kraken Wakes by John Wyndham; First Edition: Michael Joseph, 1953

Cover art uncredited

The Kraken Wakes

by John Wyndham

Michael Joseph (288 pages, 10/6, hardcover, 1953)

Cover art uncredited

Out of the Deeps

by John Wyndham

Ballantine (182 pages, $2.00, hardcover, 1953)

Cover by Richard Powers

John Wyndham was an English author, popular for five or six major novels published in the 1950s and 1960s, among numerous other books. The first of his famous novels was The Day of the Triffids (1951), about murderous walking plants and a meteor shower than causes most of humanity to go blind. Several following novels were also catastrophes of various sorts, and were published both in the UK and the US, though sometimes with variant titles. The second of these was The Kraken Wakes (UK 1953), about aliens who settle into Earth’s oceans, attack cruise liners, and subsequently wreck the climate and the world economy. It was published in the US by Ballantine as Out of the Deeps (also 1953). What I discovered only recently was that the two books are of course very similar but not identical, and nothing in either edition (in particular the US edition, presumably the second published), indicates any such differences. In fact Ballantine’s copyright page claims “This novel was published in England under the title The Kraken Wakes” which is, in fact, not literally true.