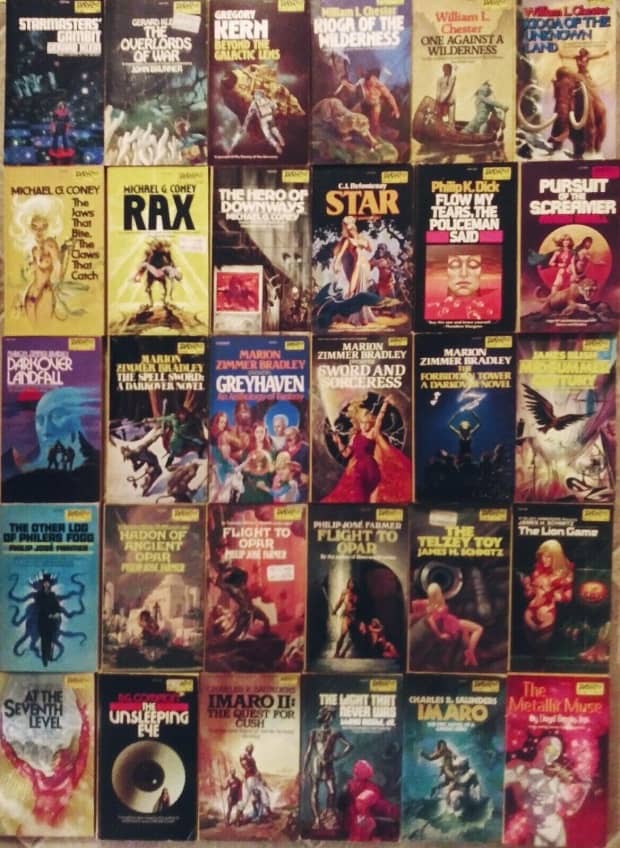

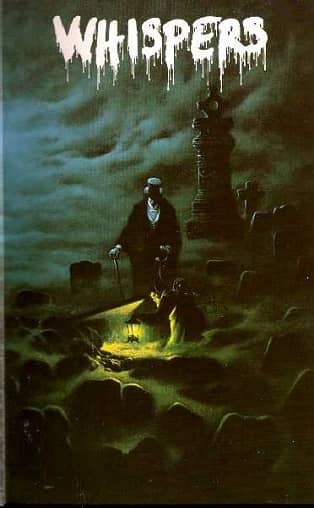

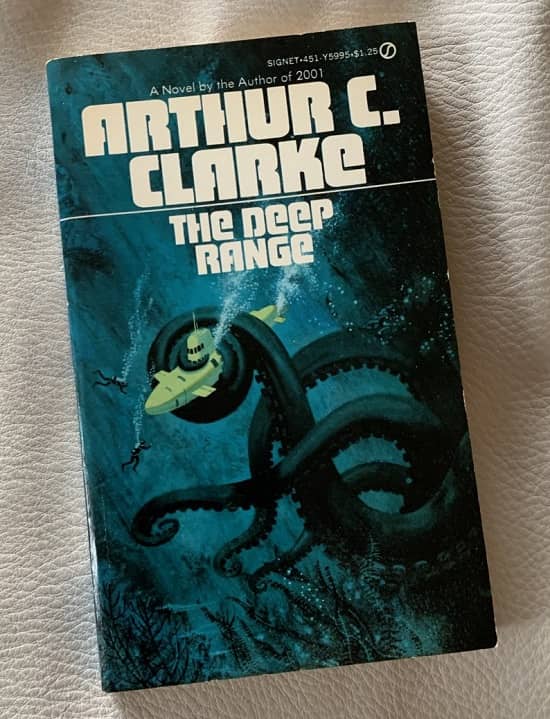

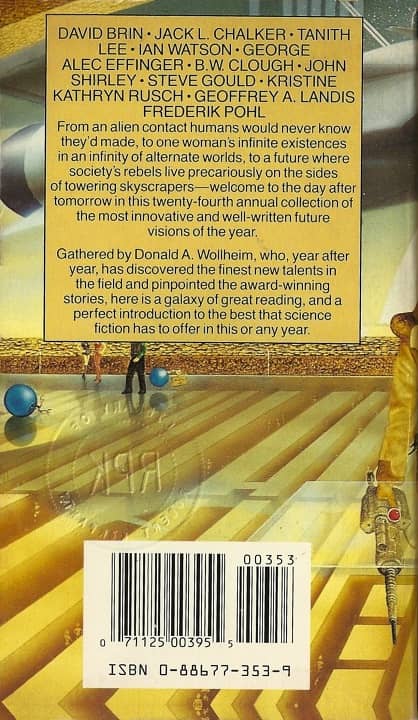

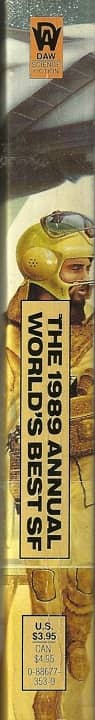

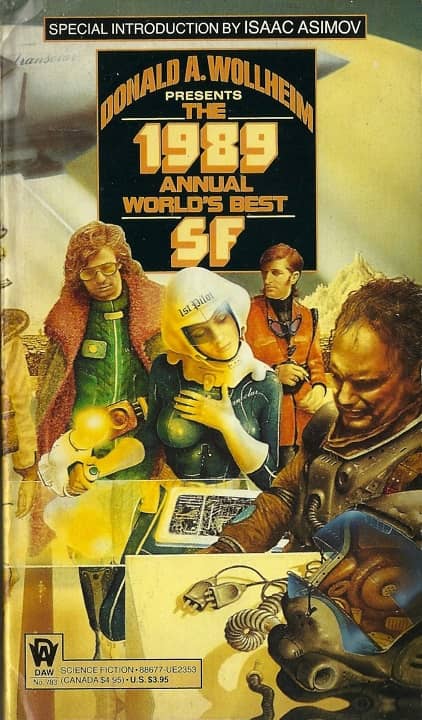

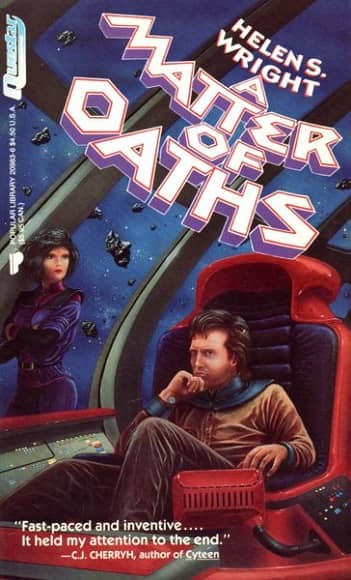

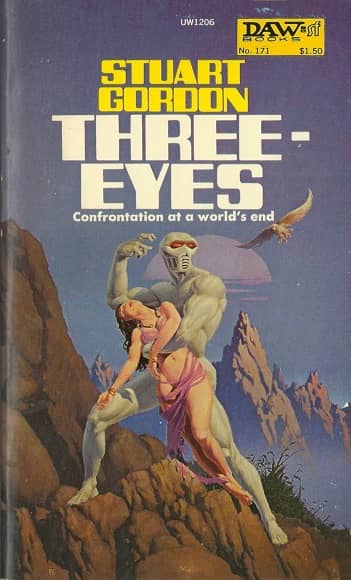

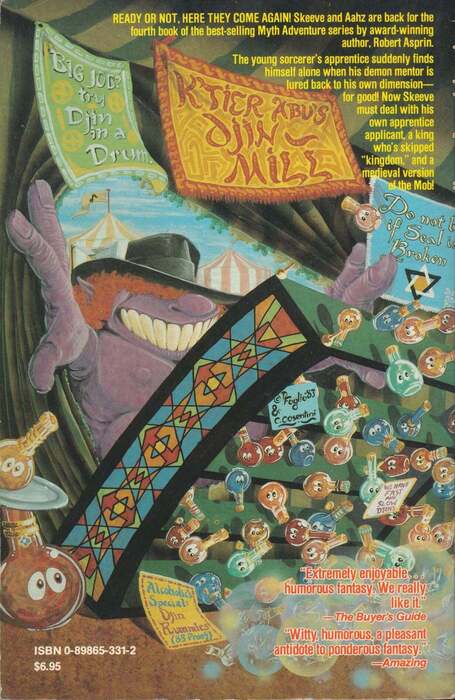

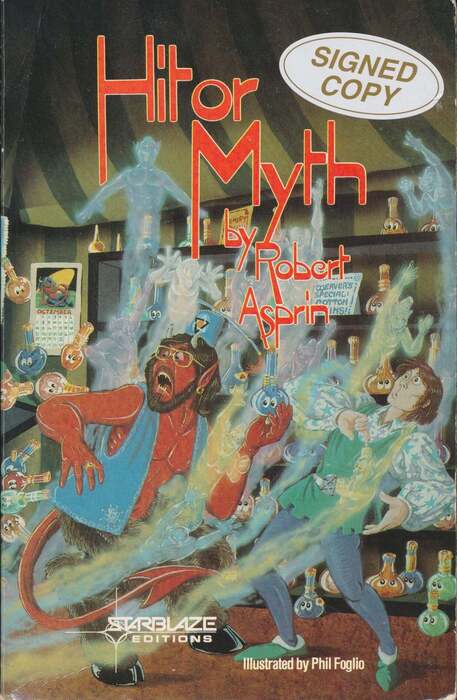

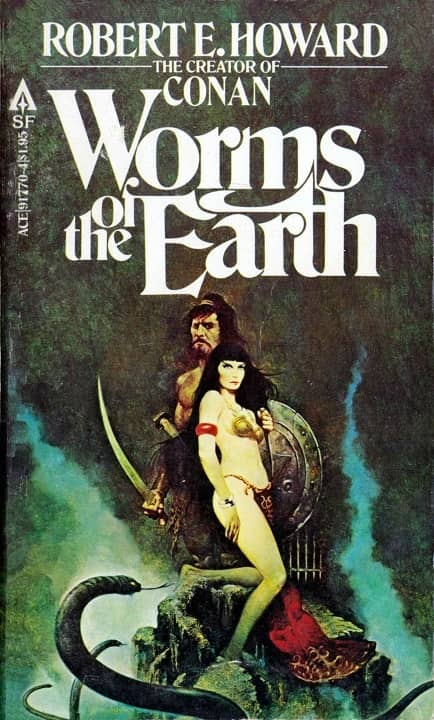

Would You Spend $44 on a Collection of 30 Vintage DAW Paperbacks?

Would you spend $44 on these 30 vintage DAW paperbacks?

I buy a lot of paperbacks on eBay. I mean, a lot. But believe it or not, I don’t spend a lot of money. I’ve gotten in the habit of buying small collections; because shipping costs work out better and I spend much less per item. I haven’t done the math recently, but I budget anywhere from $0.25 to $0.50 per book when I go hunting, and usually stick to it.

Of course, there are plenty of expensive paperbacks on eBay. Crazy-priced paperbacks, if you want to go looking for them. But eBay is also a clearing house for hundreds of individuals dumping collections en masse, often with very little description, and if you’re willing to dig a bit and take a chance, you can find bargains every day of the week. (And every hour of the day). In fact, eBay has become my go-to site for bargain-basement vintage paperback collections. Someday collectors will stop dying off, and their put-upon spouses will stop dumping their collections on auction sites at rock-bottom prices as they clean out the attic, but today is not that day.

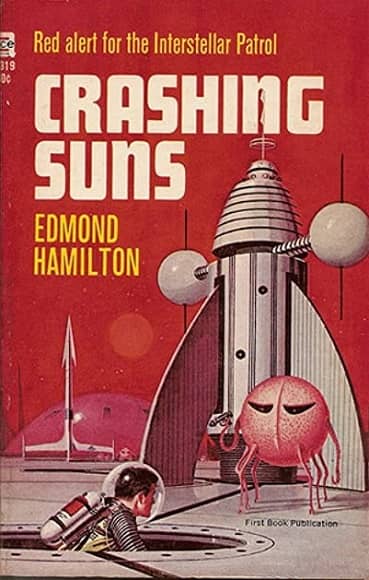

I can’t remember the last time I spent more than $25 for a lot of paperbacks. But last month I scrambled all over myself to hit the buy button on the lot above: 30 vintage DAW paperbacks priced at $44.

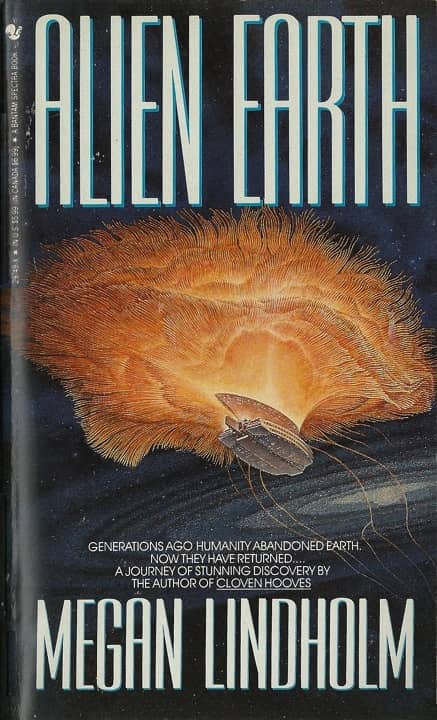

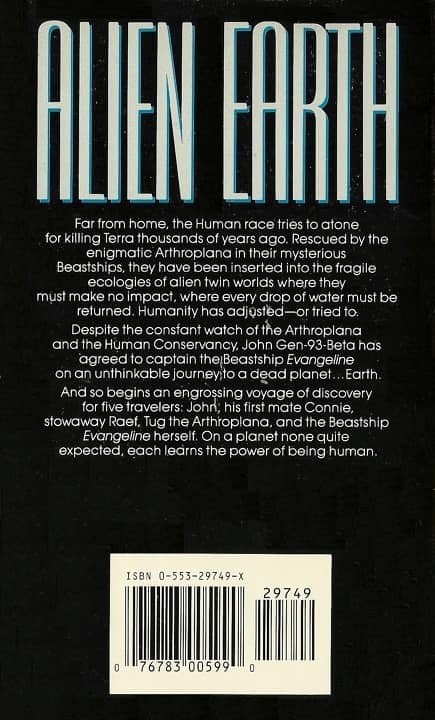

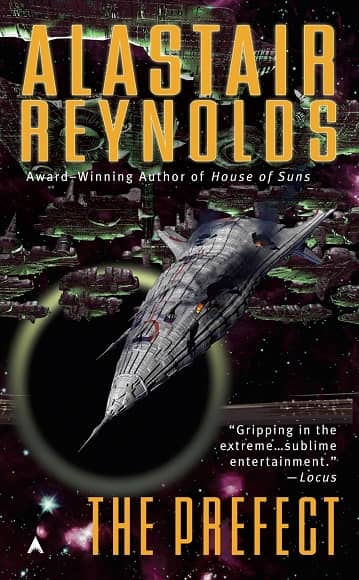

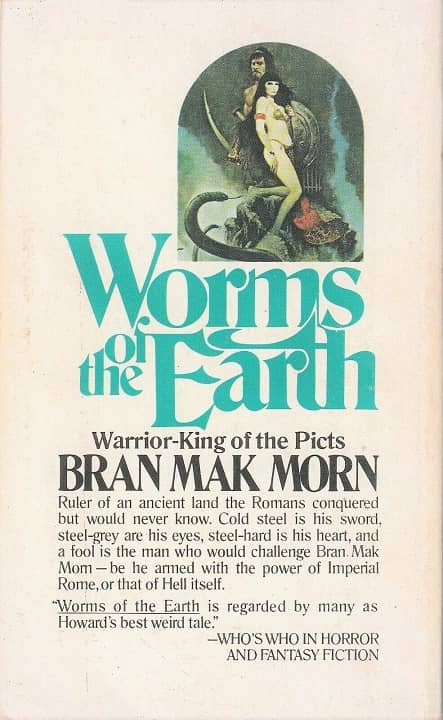

Sure, I love DAW. And I’m happy to welcome all these books into my collection, But if you look carefully, you’ll see exactly why I wrecked my monthly collecting budget to acquire these books — and would’ve been happy to spend a lot more. I didn’t buy this lot because it’s a fine assortment of books (though it is). I spent the money because of one author, and one author only. Do you know which one?