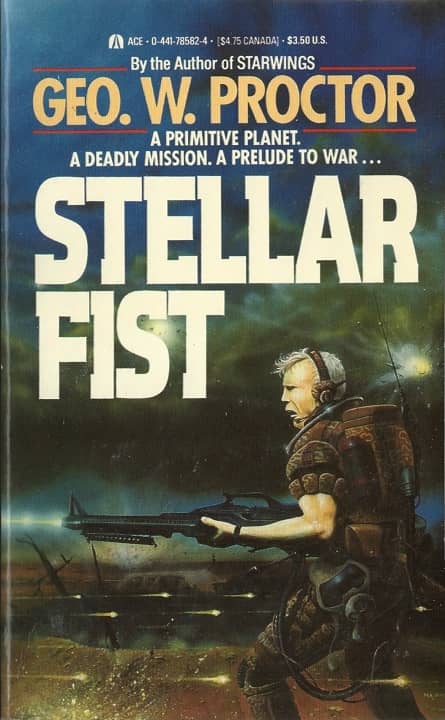

Vintage Treasures: Stellar Fist by Geo. W. Proctor

|

|

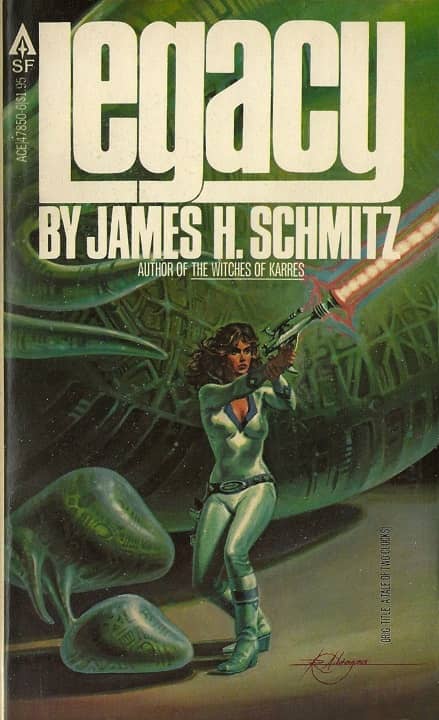

Stellar Fist (Ace, 1989). Cover by Martin Andrews

George Wyatt Proctor (1946 – 2008) was an prolific Texas author who produced some two dozen novels and collections after he retired from The Dallas Morning News in 1976. He wrote both science fiction and westerns, and collaborated with a host of well known writers, including Arthur C. Clarke, Howard Waldrop, and Steven Utley. With Robert E. Vardeman he produced nine Swords of Raemllyn sword & sorcery novels in the 80s and 90s, and with Andrew J. Offutt he contributed two novels to the Spaceways series (as John Cleve). In 1985 he wrote two novels in the long-running series V, based on the hit NBC series.

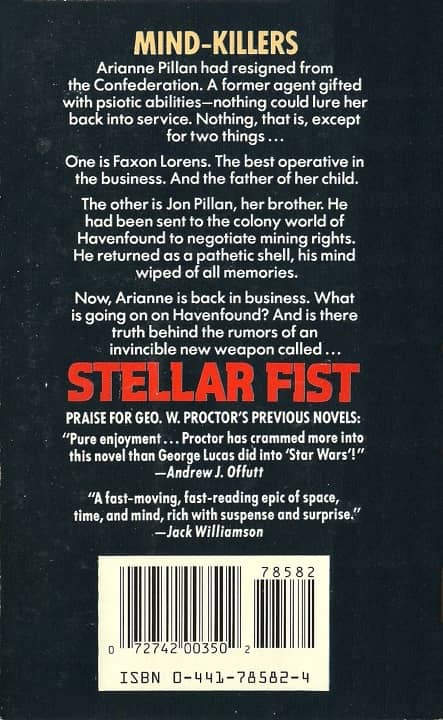

Stellar Fist was his last standalone science fiction novel, following Fire at the Center (1981) and Starwings (1984). From a modern perspective, it’s pretty much exactly what you expect from an 80s military SF novel. But that may not be a bad thing, as put so eloquently in this 2-star Goodreads review by Mark.

This book was pretty much awful, but I found myself really enjoying it — from the ridiculous interstellar-sexpot-spy-turned-time-traveling-lounge-singer-returned-interstellar-spy to the last 20 pages of complete story- and character-breaking chaos. Would highly recommend reading it if you’ve got a sense of humor and nothing better lying around.

That reads like a solid recommendation in my book.

Stellar Fist was published by Ace Books in January 1989. It’s 229 pages, priced $3.50. The cover is by Martin Andrews. It has never been reprinted, which really isn’t very surprising.

See all our recent Vintage Treasures here.