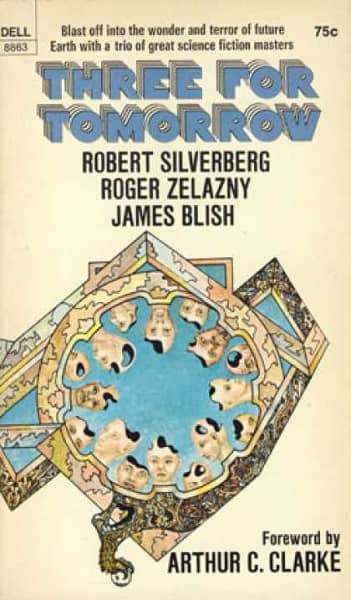

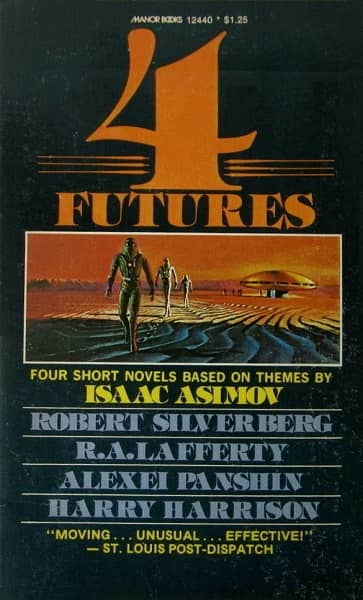

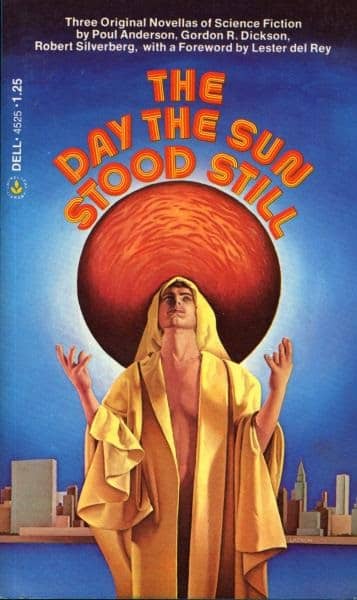

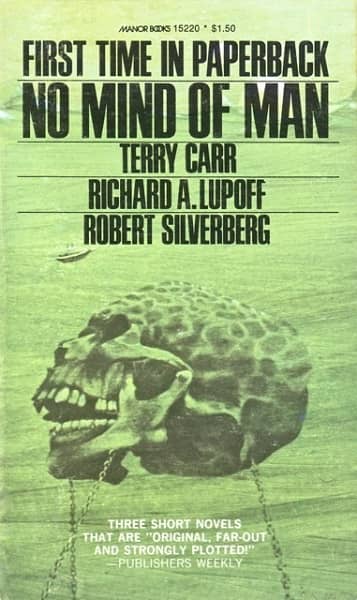

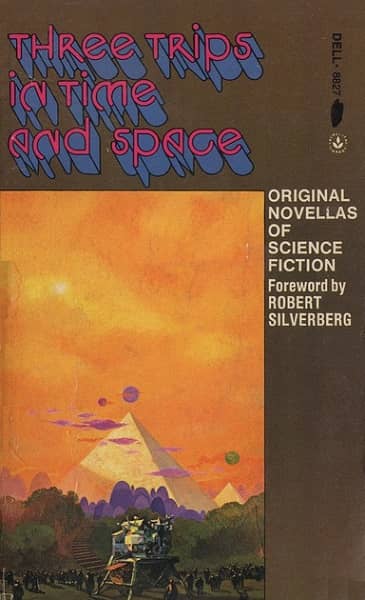

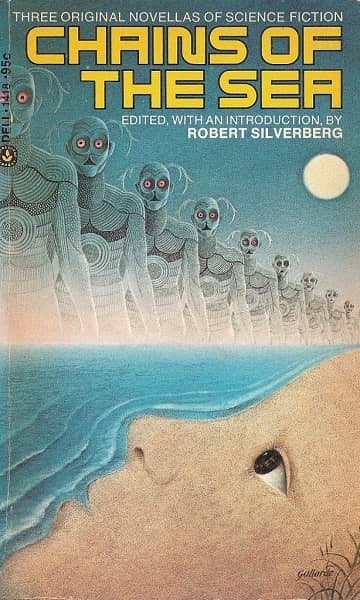

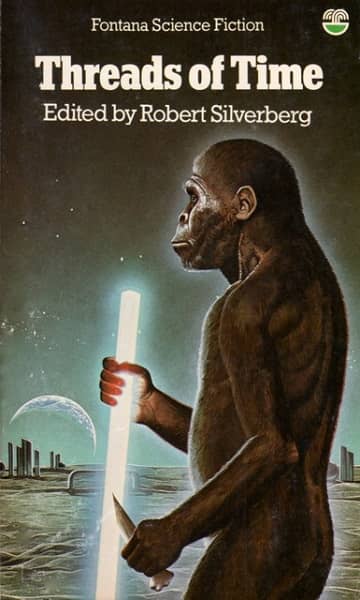

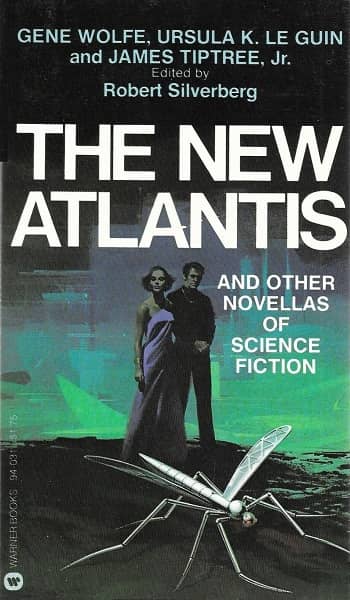

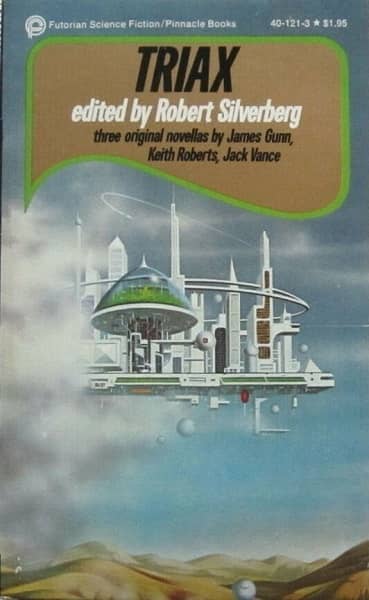

Paperback editions of Silverberg 70s original anthologies. Published by (left to right, from top left):

Dell, Manor Books, Dell, Manor Books, Dell, Dell, Fontana, Warner Books, Pinnacle

In 1966 Robert Silverberg published his first anthology, an unassuming volume titled Earthmen and Strangers from staid New York press Duell, Sloan and Pearce, known mostly for the infamous U.S. Camera 1941 annual that was banned in Boston for daring to include nudes. Earthmen and Strangers was hugely successful, remaining in print for an astonishing two decades, with paperback reprints from Dell, Manor Books, and Bart Books, and Silverberg was off to the races as an editor. Over the next five decades he published dozens of science fiction anthologies, including a handful of bestsellers like the seminal Legends (1998) and its science-fictional sequel Far Horizons (1999).

Beginning in the late 60s and all through the 70s Silverberg produced a steady stream of original anthologies, most of which had a signature format: each contained three novellas from the biggest names in the industry, including major award nominees by James Blish, Gordon R. Dickson, Jack Vance, Clifford D. Simak, Norman Spinrad, Gene Wolfe, Ursula K. Le Guin, and James Tiptree, Jr. — plus novellas by Roger Zelazny, R. A. Lafferty, Harry Harrison, Alexei Panshin, Poul Anderson, Larry Niven, John Brunner, George Alec Effinger, Gardner Dozois, Gregory Benford, Joan D. Vinge, Vonda N. McIntyre, Keith Roberts, James Gunn, Phyllis Gotlieb, and many others.

Like Terry Carr’s Universe, Damon Knight’s Orbit, and Silverberg’s own New Dimensions, these anthologies were prestige fiction markets, appearing in hardcover and distributed to libraries, and getting a lot of attention when awards season rolled around. As a result they attracted a lot of talent. Silverberg was a master with a keen eye for emerging talent, and an uncanny ability to coax top-notch work of out his contributors. The books still make entertaining reading today.

…

Read More Read More