Vintage Treasures: Life During Wartime by Lucius Shepard

|

|

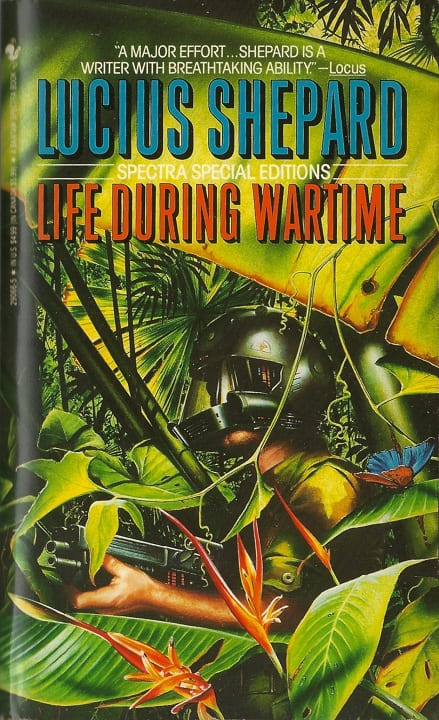

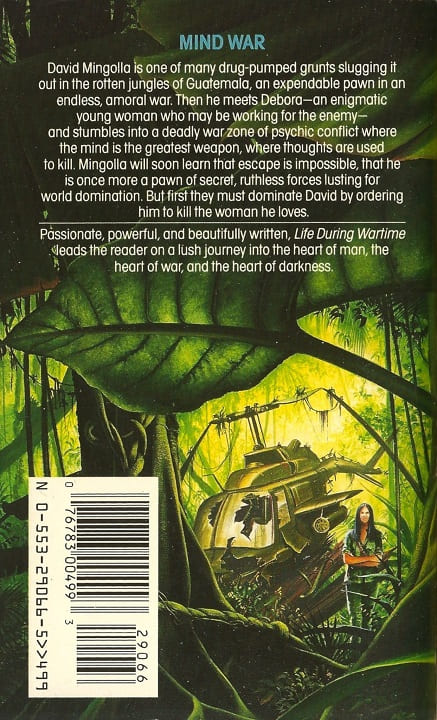

Life During Wartime (Bantam Spectra paperback reprint, July 1991). Cover by Mark Harrison

In April 1986 Lucius Shepard published his famous novella “R&R” in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine. It was the tale of young David Mingolla, an American draftee reluctantly fighting a war in a near-future Central America, where psychics predict enemy movements and soldiers are fed a cocktail of experimental combat drugs. It was an immediate hit, nominated for a Hugo Award and winning the SF Chronicle, Locus, and Nebula Awards.

Shepard expanded it into Life During Wartime in 1987, his most successful novel, nominated for the Locus, Dick, and Clarke awards. I read it in the summer of 1988 and found it filled with haunting scenes. It’s perhaps the most memorable SF depiction of war I’ve ever seen, a scathing indictment of American interventionism, with insane A.I’s (who still make more sense than the war), secret psy-ops, a Heart of Darkenss-like trek through a twisted and lethal jungle, and the dark secret of the war’s origins waiting for Mingolla at the end of his harrowing journey.