A British Country Mystery in Space: Murder on Usher’s Planet by Atanielle Annyn Noël

|

|

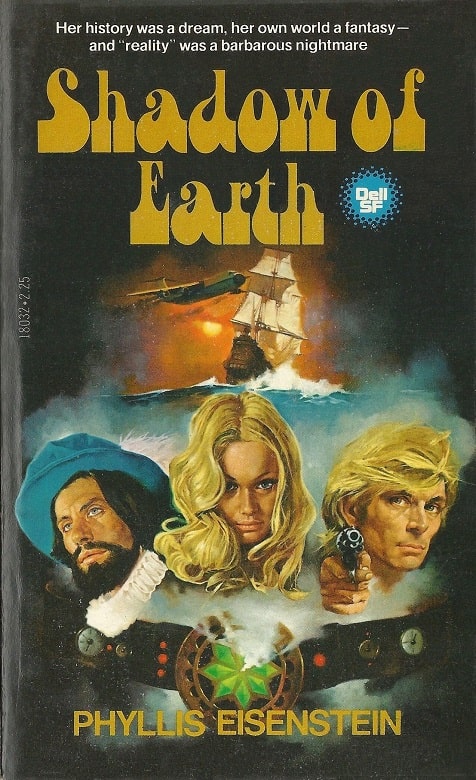

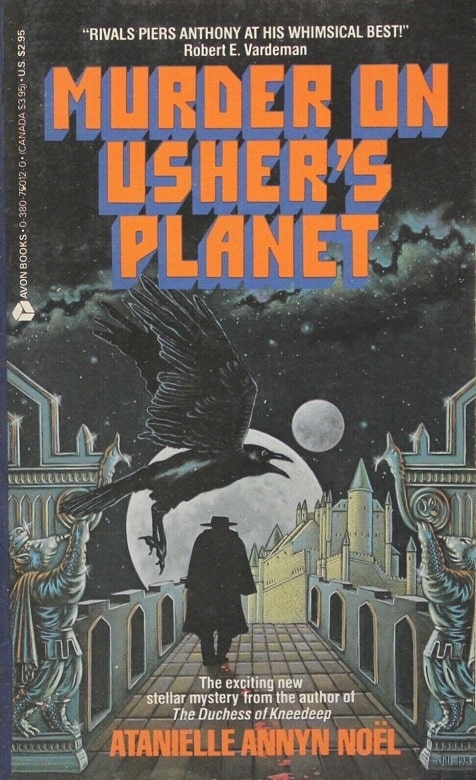

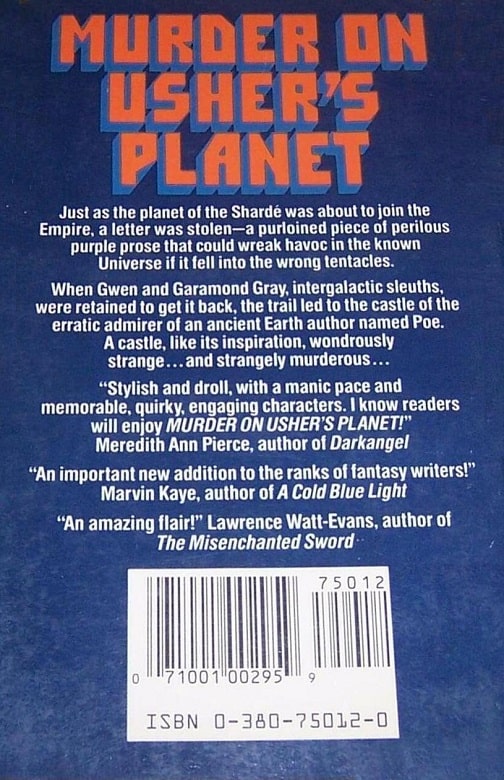

Murder on Usher’s Planet (Avon, April 1987). Cover by Jill Bauman

I’m going to be reviewing a few novels, of ‘70s/’80s vintage, that were foisted on me generously given to me by Black Gate’s panjandrum, John O’Neill. For his sins, he gets to publish these reviews here in Black Gate!

I exaggerate – I bought some of these novels of my own volition (though often because John alerted me to their existence with a Black Gate Vintage Treasures article!) and I am sincerely grateful to John for those he did give to me, and those he made me aware of, either by pointing them out at a convention, or by writing about them. The novels I’m looking at now do cluster in the ‘70s and ‘80s – a period James Davis Nicoll likes to call the “Disco Era.” And I think it’s worthwhile to consider books from that period – when I was a teenager or a newly hatched adult – especially the more obscure books. But this does mean a good many of these reviews might not be, er, entirely positive!

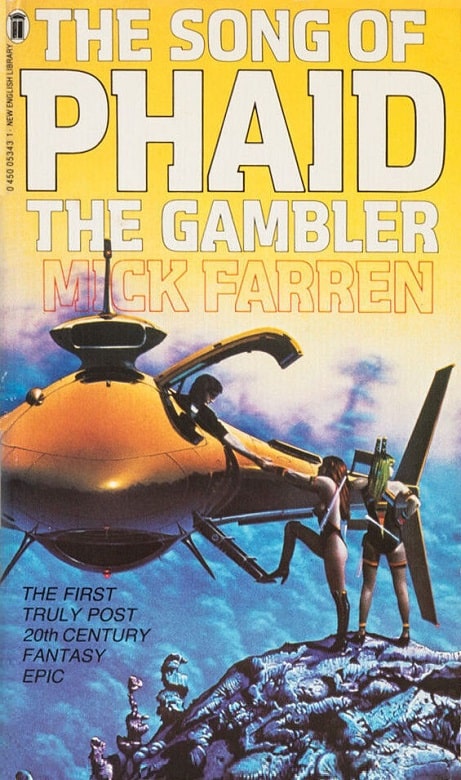

The first review to fit this paradigm might be my look at Mick Farren’s The Song of Phaid the Gambler (1981). And now we come to Murder on Usher’s Planet, by Atanielle Annyn Noël, published by Avon in 1987 (just as the Phaid the Gambler books appeared in the US.) This actually was a gift from John – we were wandering through the dealers’ room at the Chicago Pulp and Paper convention a few months ago, and I noticed this book, largely I think because of the author’s unusual name; and John grabbed it (along with a few others for himself, as I recall), and having bought it, pressed it on me – suggesting that if I read it I should review it for Black Gate. And here we are!