Vintage Treasures: The Med Series by Murray Leinster

|

|

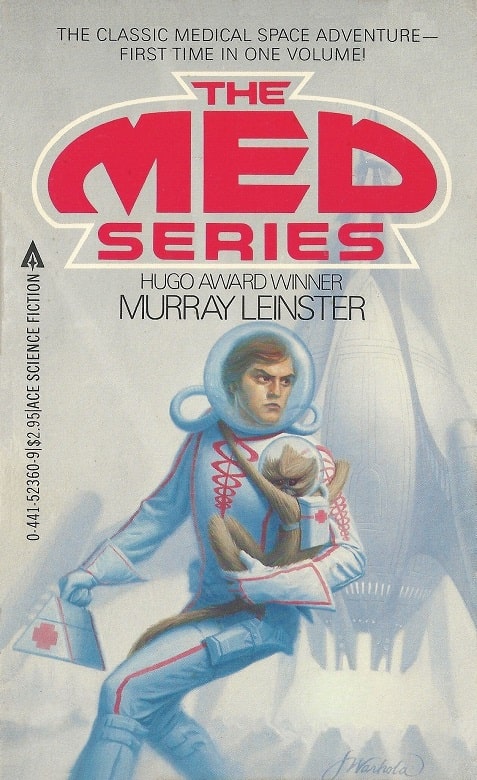

The Med Series (Ace, May 1983). Cover by James Warhola

For most of its life John W. Campbell’s Astounding Science Fiction was the most important SF magazine on the stands. It was the beating heart of the genre in a way that’s tough to comprehend today, in a market that’s grown far beyond print.

Campbell made his mark by discovering, nurturing, and publishing the most important writers of his day. But — quite cleverly, I think — he also cultivated lifetime readers by making Astounding home to exciting and highly readable series, many of which were later successfully packaged as bestselling books. Readers of Astounding knew they were getting an early look at the titles everyone would eventually be talking about.

A study of the major SF series launched in Astounding would fill several volumes, but they include Frank Herbert’s Dune, Asimov’s Foundation and Robot tales, Anne McCaffrey’s Dragonriders of Pern, H. Beam Piper’s Paratime and Federation/Empire sagas, Gordon R. Dickson’s Dorsai!, Poul Anderson’s Psychotechnic League, James Schmitz’s Telzey Amberdon and The Hub tales, and countless others.

One of my favorite story cycles from the Campbell era of Astounding was Murray Leinster’s The Med Series, the tales of the intrepid doctors of the Interplanetary Medical Service “roving through the uncharted vastness of deep space.” They were eventually repackaged in a handful of paperbacks that are long out of print, but still fondly remembered by a few of us old timers.