Andre Norton: Gateway to Magic, Part II

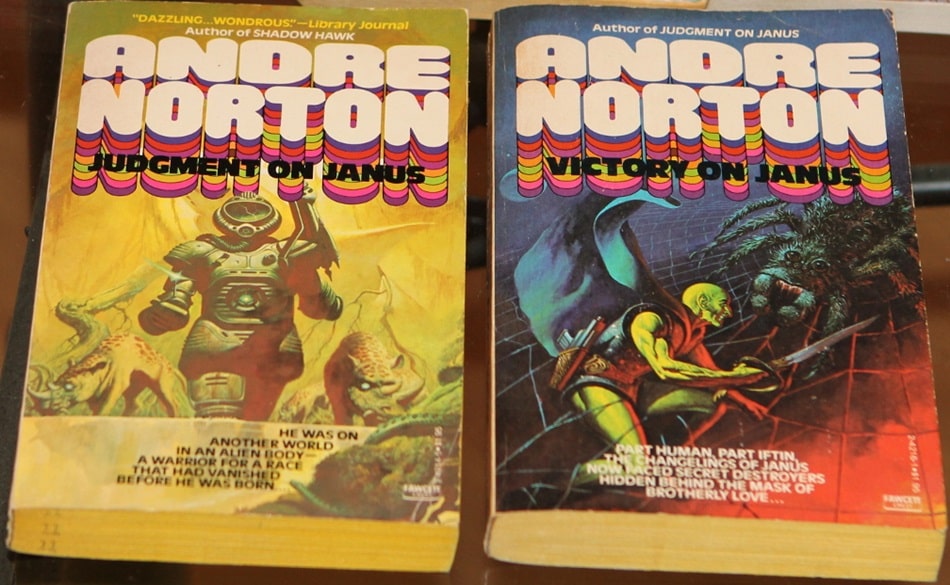

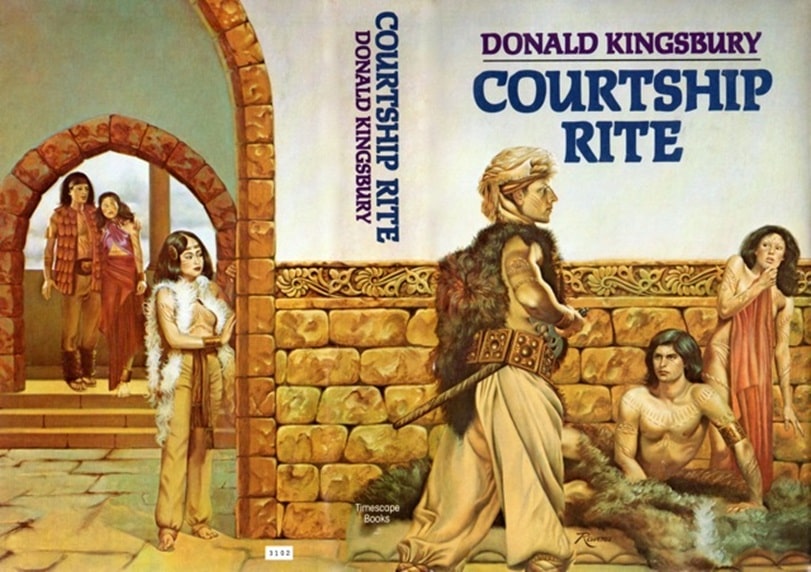

Andre Norton’s two-book series Judgment on Janus and Victory on Janus

(Fawcett Crest, December 1979 and January 1980). Covers by Ken Barr

Part I of Andre Norton: Gateway to Magic is here.

Two other fun books by Norton that I read between ages 12 and 16 were Judgment on Janus and Victory on Janus. In Judgement, a down and out young man named Naill Renfro ends up on the planet Janus, which is ruled by a group of religious fanatics from Earth. There are artifacts on Janus from a native civilization, which is thought extinct, and Renfro finds one but is contaminated by it and begins to mutate. Turns out, he’s mutating into a native of the planet, a changeling, if you will. He flees into the vast forest of Janus.

When I first read this book, I was caught up in the rousing adventure, which had elements of the Sword & Planet genre. Only with a later read did I realize all the things going on underneath the surface, the condemnation of religious fanaticism and racism, and the criticism of a corporate world of excess. I came around to that way of thinking myself many many years later. She was ahead of her time here.