My father would have been 75 today.

I can’t help thinking about him on the day of his death, in May — I think about him most days, although after seven years the pain of his absence is no longer an ever-present ache — but I forcibly choose to celebrate his memory on his birthday.

I don’t do anything elaborate. Dad’s birthdays were never elaborate occasions when he was alive, though sometimes finding a gift could be. There wasn’t much he really lacked; he took comfort and pleasure in the people he loved and the things he already had. On his birthdays these days I take down his picture, light a candle, sit down with a good drink, and think out loud. Those steps are likely some kind of tradition, somewhere. I’m sure I didn’t make them up out of whole cloth.

A few years back I used to get choked up whenever I talked to my children about my father, and I was so obviously affected that my son said, one day, that he’d stop asking about his grandfather because the topic so clearly upset me. That obviously wasn’t the route I meant to travel. Today I can tell my children all sorts of tales about their grandfather.

Regular visitors will note that I usually talk about either Black Gate or writing matters. This may be the first time I’ve strayed into more private concerns for any length of time, but then my parents were instrumental in a lot of my interests. It was my friend Mike Boone who really introduced me to science fiction; he gave me my first phone call ever (I was 5) to let me know that the “new” show he’d told me about was on (the original Star Trek, in reruns). Dad wasn’t a fan, but he turned over whatever he was watching just in time for me to see Kirk and Spock beaming down. I was hooked immediately. My mother loves science fiction and fantasy, and as I grew older she handed me book after book, series after series. Neither genre was Dad’s thing, but he loved to talk writing. Once he was discussing Jungian archetypes and their influence on mythology, indeed, upon all stories, and I asked him to perform an analysis of Star Trek. Dad said that Kirk was obviously the hero, and his internal dilemmas were played out between Spock, his reasoning half and McCoy, his emotional half. “What about Scotty?” I asked.

Dad thought for a moment. “He’s some aspect of the physical.”

His analysis impressed young teenage Howard — moreso, apparently, than most of our other talks about writing, which my feeble memory has already garbled or forgotten, just as it has confused my recollection of where we had that particular talk. In the living room, whilst standing on our brown carpet, or did the whole thing take place while we were jogging north from the park? All I recall now are the words, and I curse myself for not remembering more.

All this talk of Dad and story theory may leave you with the impression that he was an egghead, or ivory tower intellectual. He wasn’t. At Dad’s funeral, one of his best friends called him the most unassuming intellectual he ever knew. Dad never trumpeted his knowledge. If you wanted to talk Moby Dick or Hawthorne he was all for it, but he was just as happy to talk golf swings or basketball or car repair.

He took early retirement and left the university to master piano tuning. I was married and living in Kansas by then, and the thought of him tuning anything professionally horrified me. He’d always used me rather like a sound meter before playing his guitar, and over the years his ear never seemed to improve. I was under the impression that you either had a good ear or you didn’t and there wasn’t much you could do about it. Dad proved me wrong. Soon he was not only tuning pianos, he was rebuilding and refurbishing them. The last time we talked, however, he had been playing piano. The keyboards had always been my instrument and Dad came to it later in life. He was asking me advice about improvising good bass lines.

When I heard from Mom a few days later I assumed she was calling to check up on my three-year-old, who’d just had his tonsils removed. No. Dad had died, instantly, of a heart attack. The only mercy was that someone saw him fall and CPR assistance was almost immediate. We know, then, that if there was anything that could have been done, the help was there to do it. It was already too late.

I miss him terribly.

Howard

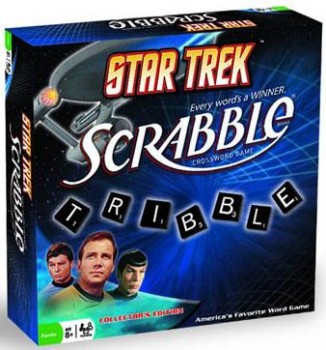

Recently I had occasion to visit the toy store — a rarity in a life spent avoiding children as much as possible — and was sort of blown away by how different it was than I remembered. The last time I was in a toy store was probably as a pre-teen buying Advanced Dungeons & Dragons books (yes, unbelievable as it seems, Fiend Folio and Unearthed Arcana used to share self space with Teddy Ruckspin and Cabbage Patch Kids at the local Toys ‘R Us) and, while I wasn’t surprised to see a complete lack of anything RPG in my visit, what did impress me is just how much fantasy and scifi oriented material I did find — you might even say the place was a juvenile spec fic warehouse, though with a side order of dinosaurs, pirates, and the occasional pony.

Recently I had occasion to visit the toy store — a rarity in a life spent avoiding children as much as possible — and was sort of blown away by how different it was than I remembered. The last time I was in a toy store was probably as a pre-teen buying Advanced Dungeons & Dragons books (yes, unbelievable as it seems, Fiend Folio and Unearthed Arcana used to share self space with Teddy Ruckspin and Cabbage Patch Kids at the local Toys ‘R Us) and, while I wasn’t surprised to see a complete lack of anything RPG in my visit, what did impress me is just how much fantasy and scifi oriented material I did find — you might even say the place was a juvenile spec fic warehouse, though with a side order of dinosaurs, pirates, and the occasional pony. Star Trek (2009)

Star Trek (2009)