A Tale of Two Covers: Akata Warrior by Nnedi Okorafor

|

|

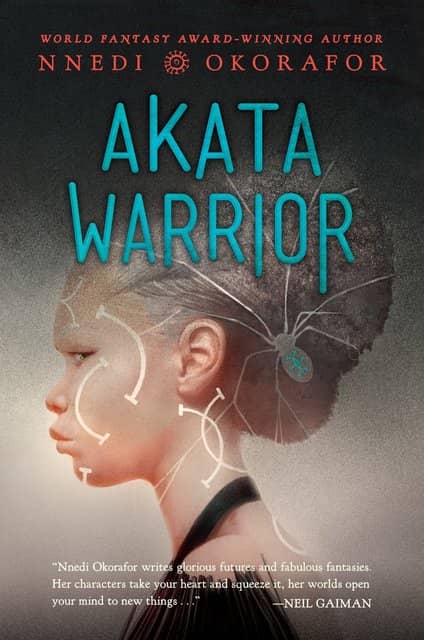

Nnedi Okorafor is one of the most exciting novelists at work in the field of fantasy. She’s won the Hugo, Nebula and World Fantasy Awards, and the Wole Soyinka Prize for Literature in Africa. She writes Black Panther comics for Marvel, and her World Fantasy Award-winning novel Who Fears Death is being developed by George R.R. Martin as an HBO series.

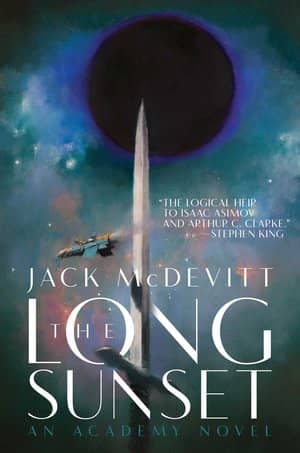

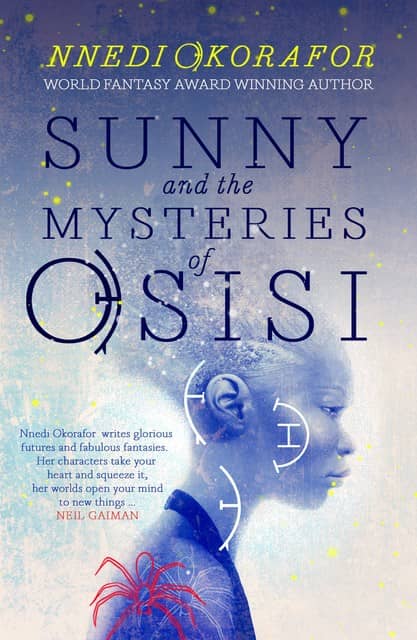

Her latest novel, Akata Warrior, was published by Viking Books for Young Readers last October (above left, cover by Greg Ruth). It was republished in the UK in March by Cassava Republic Press under the title Sunny and the Mysteries of Osisi (above right, design by Anna Morrison). Both books (er, the single book) are (is?) the sequel to 2011’s Akata Witch.

Although the books are being sold to separate markets with different titles and different covers, I was struck at just how similar the cover images are. In fact, both use Greg Ruth’s core image of a woman with a black scarf (albeit flipped), and both make use of overt spider imagery, along with an overlay of curvy white Nsibidi symbols on her skin. Both also use the same quote by Neil Gaiman. Note the differences, however — the British cover has markedly different hair, and a completely different color tone. She’s looking in different directions as well.