Birthday Reviews: Alfred Coppel’s “Mars Is Ours”

Alfred Coppel was born on November 9, 1921 and died on May 30, 2004.

Coppel published under a variety of pseudonyms, including Sol Galaxan, Robert Cham Gilman, Derfla Leppoc, A.C. Marin, G.H. Rains, and sometimes attaching a Jr. to the end of his own name. In addition to writing science fiction, he wrote for the pulps in a variety of genres, including thrillers and military stories. His best selling book may have been the 1974 thriller Thirty-Four East about the Arab-Israeli conflict.

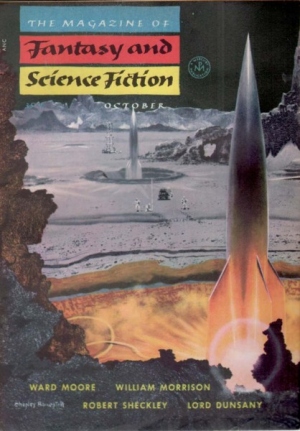

“Mars Is Ours” was first printed in the October 1954 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, edited by Anthony Boucher. It was translated into French in 1955 for publication in Fiction #19 and was reprinted in France in 1985 in the anthology Histoires de Guerres Futures, edited by Demètre Ioakimidis, Jacques Goimard, and Gérard Klein. Its only English language reprint was in Fourth Planet from the Sun, edited by Gordon van Gelder, which collected stories about Mars originally published in F&SF.

Unfortunately, writing a tale too closely tied to a political situation can completely date the story, which is why so many authors create analogs for political forces. Coppel did not do this in “Mars Is Ours,” which tells about a proxy war between the United States and the Soviet Union being fought on the red planet.

Marrane is in charge of a group of American soldiers on Mars who are intent on wiping out the Soviet base. He knows, as must the Soviets know, that their war is coming to an end. There is little in the story to require it be set on Mars rather than a distant outpost on Earth, although near the end of the story, the distance to Earth and the non-terrestrial environment do come into play enough that the story would have been different had it been set in Mali or Colombia rather than on Mars.