Spotlight on Interactive Fiction: More Superheroes!

Last week, I talked about superhero webcomics, and there was some fun discussion in the comments about superheroes and fantasy and where those genres meet. Fritz Freiheit also pointed me in the direction of his slightly out of date “A Brief Overview of Superhero Fiction,” which means I’m going to have a bunch of novels to add to my TBR pile. But prose and comics aren’t the only homes of superheroes: there are a handful of interactive fiction games that let you become a super yourself. Lest you think I play a vast majority of my interactive fiction games from Choice of Games (disclosure: actually, that’s true, but I do try to diversify for this column), in this spotlight, we have two superhero games to compare and only one is from Choice of Games.

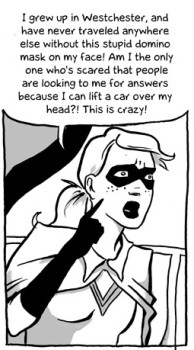

Heroes Rise: The Prodigy is the first Heroes Rise game by Zachary Sergei. (The second, Heroes Rise: The Hero Project, I have yet to play.) In it, you are a beginning hero, just on the verge of getting your license to be an official hero in Millennia City. You live with your grandmother, who has a Power with plants, because your superhero parents were arrested for the accidental killing (the court said “murder”) of a supervillain. Your family relationships are fraught, but you’re getting ready to take Millennia City by storm.