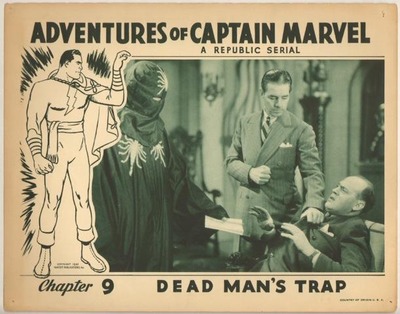

Secret Caverns and Death Traps: The Adventures of Captain Marvel, Chapter Nine: Dead Man’s Trap

A seat in the balcony today? Good choice — the view is great from up here, and during the slow stretches that are inevitable in any Bette Davis picture (you know, all that kissing), there’s always the fun of candy-bombing your friends down below. But before we get to any of that, there’s this week’s edge-of-your-seat installment in The Adventures of Captain Marvel, “Dead Man’s Trap.”

A seat in the balcony today? Good choice — the view is great from up here, and during the slow stretches that are inevitable in any Bette Davis picture (you know, all that kissing), there’s always the fun of candy-bombing your friends down below. But before we get to any of that, there’s this week’s edge-of-your-seat installment in The Adventures of Captain Marvel, “Dead Man’s Trap.”

Three title cards will remind us of the situation at the end of the previous chapter. “Billy Batson — And Whitey accuse Doctor Lang of being the Scorpion.” “Doctor Lang — Tries to take Billy to a place of safety in his car.” “The Scorpion’s men follow in Billy’s car which has been mined.” Now for the amazing acronym that will transport you to realms of action and adventure far beyond the ken of classmates who couldn’t scare up the price of admission! Shazam!

Recapping last week’s conclusion, Lang and the unconscious Billy hurtle down the road, closely pursued by two Scorpion thugs. The goons are blissfully unaware that there’s a bomb under their hood that will detonate when they exceed fifty miles per hour. As this is going on, back at Lang’s house the gate guard (a Scorpion stooge — damn that temp service) calls the Scorpion’s head henchman, Barnett, and tells him that Lang and Batson have driven out on the Mill Valley Road; Barnett jumps in a car with two other goons to head them off.