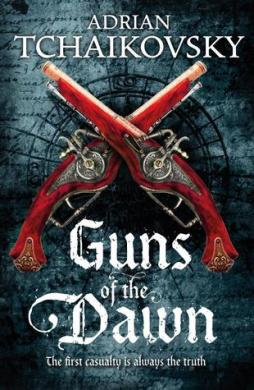

Epic Musket Fights and Vampire-Like Magic: Guns of the Dawn by Adrian Tchaikovsky

(This weekend, I’ll be doing my thing at Conpulsion, Edinburgh’s truly excellent gaming convention. If you’re there, drop by and say hello.)

Guns of the Dawn

Adrian Tchaikovsky

Tor UK (700 pages, February 12, 2015, £16.99 in hardcover, £7.99 digital)

Adrian Tchaikovsky’s Guns of the Dawn is…

Imagine Pride and Prejudice meets Sharpe, or if some of the female characters of the Cherry Orchard got conscripted into All Quiet on the Western Front, or was it Red Badge of Courage or Catch 22?

With Magic.

In a nutshell, two vaguely 1800s nations go to war. As attrition grinds down her side’s army to the point where they are conscripting women, upper class Emily decides not to draft dodge and goes to war, in a red coat, with a musket, ultimately in a swamp. And somewhere in there, there is an emotionally complex romance, coming of age, a mediation on truth and propaganda, and a hint of… but that would be a spoiler.

Actually, the whole X meets Y thing breaks down very quickly. “Oh this is the French Revolutionary War..? or is it the American Revolution? Or…”

Tchaikovsky is obviously well-read, has life experience, understands war and organisations, and people, and if there are parallels with classic literary works and moments of Military History, it’s because they in turn reflect truths about life and people. Though, as I read on, I got the sense that he was quietly enjoying playing with reader expectations. Just sometimes, you think, “Oh I know how this goes. This is a Rorke’s Drift sequence…” and then it’s not.