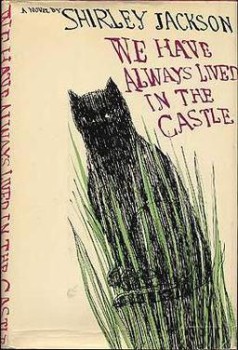

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson

My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance. I have often thought that with any luck at all I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both my hands are of the same length, but I have to be content with what I had. I dislike washing myself, and dogs, and noise. I like my sister Constance, and Richard Plantagenet, and Amanita phalloides, the death-cap mushroom. Everyone else in my family is dead.

So opens Shirley Jackson’s final novel, We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962). Published three years before her death, this introduction to the book’s narrator, better known as Merricat, seems to promise readers they are in for the story of a quirky young woman. It is indeed beguiling but bears only the slightest hint of what’s to come in this short novel. It is a book built of dark and deep shadows, pierced at times by shimmering passages, before becoming darker and more claustrophobic.

Merricat lives with her sister and their crippled and addle-minded Uncle Julian in the great mansion that the Blackwoods have always lived in. Six years ago something terrible happened for which all the townsfolk hate, and perhaps even fear, the Blackwoods. One evening, arsenic found its way into the sugar bowl and the sisters’ parents, younger brother, and aunt died. Their uncle took less sugar and survived, though irreparably broken. Constance, who cooked, who never took sugar — and who cleaned the sugar bowl before the police arrived — was accused and tried. No motive could be found and she was acquitted, but she has never since left the property. Only Merricat braves the village — twice a week — to buy food, take out books from the library, and suffer the staring and unpleasant treatment of the villagers.

I’ve finally read

I’ve finally read