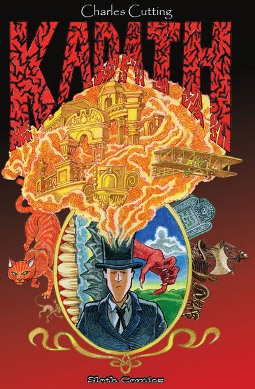

Lovecraft’s Dreamlands Via Graphic Novel: Charles Cutting’s Kadath

HP Lovecraft is a bit like Bill Haley; he arguably created his own genre, but few people now consume his work for simple pleasure.

Just as modern people typically discover Rock and Roll through [your favourite band here], they come to the Cthulhu Mythos through Charles Stross’s Laundry Files(*), through the madness of the Cthulhu Fluxx cardgame, or through the roleplaying game Call of Cthulhu.

Kids…? Well my daughter (8) has a plush Cthulhu who spends most of his time in the naughty corner for trying to eat the faces of the other toys.

Nobody, typically, just happens to pick up an HP Lovecraft book. If they do, they probably bounce. Let’s just say that speculative fiction has produced better stylists and that “of his time” is proving to be less and less able to explain away his racism.

However, unlike Bill Haley, Lovecraft still owns his genre. He pretty much nailed Cosmic Horror, and though we have chipped off racist carbuncles, all the tropes still bear his mason’s mark.

This means that Lovecraft’s Mythos serves the the same function in the Geek community as the Classical world served amongst educated Victorians. They would remark on somebody being “Hector-like”, we joke that our pasta bake “turned into a Shoggoth”.

This creates the interesting problem that the our shared subculture leans heavily on a set of texts that are increasingly unreadable for both literary and ethical reasons!

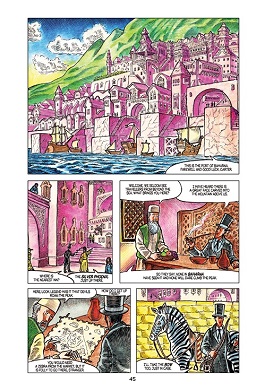

The answer, of course, is to retell the stories in other media, which is where books like Charles Cutting’s graphic novel Kadath come in.