September Short Story Roundup

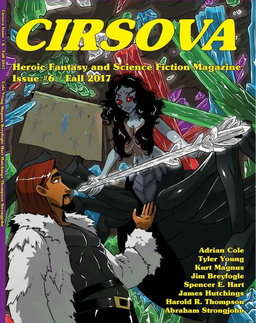

Another month, another roundup. While I’m still dubious of any sort of serious swords & sorcery revival, there is most definitely a renewed interest in the older roots of fantasy and science fiction going on. Howard Andrew Jones is editing a new magazine, Tales from the Magician’s Skull, that is inspired by Gary Gygax’s fabled Appendix N. The folks at Castalia House have built up a serious following based on their love of pulp and Appendix N. One of the most serious proponents of some sort of pulp restoration is P. Alexander, editor of Cirsova magazine.

Another month, another roundup. While I’m still dubious of any sort of serious swords & sorcery revival, there is most definitely a renewed interest in the older roots of fantasy and science fiction going on. Howard Andrew Jones is editing a new magazine, Tales from the Magician’s Skull, that is inspired by Gary Gygax’s fabled Appendix N. The folks at Castalia House have built up a serious following based on their love of pulp and Appendix N. One of the most serious proponents of some sort of pulp restoration is P. Alexander, editor of Cirsova magazine.

The latest issue of Cirsova, #6, is 126 pages long and contains seven stories and an installment in an ongoing epic poem about John Carter of Mars. There’s more of a science fiction emphasis in this issue than suits my tastes at present, but that doesn’t detract from its general high quality.

The magazine kicks off with “The Last Job on Harz,” by Tyler Young. When a party of miners is wiped out in horrible fashion on the planet Harz, two government agents are sent out from Earth to investigate and protect the interests of the Company. The Company, properly known as Universal Resources, is one of those monolithic businesses found across science fiction. The agents quickly discover that some heretofore unknown entity, in fact a whole herd of entities, is at large on Harz.

Aside from the overly familiar basic plot of the story and its too-obvious conclusion, “The Last Job on Harz” skips out on most of the action. Maybe it’s just me, but in a story featuring creatures described as a cross between a praying mantis and a kangaroo and with “an armored, segmented body, long arms ending in curved claws, and a narrow insect-like head,” I want more of them. Too much of the tale is given over to not very exciting detective work, and the most interesting of that takes place off camera.

“Death on the Moon” by Spencer H. Hart, flips the setup of the previous tale. Bert Henderson is an agent from one of those sci-fi monopolies, in this case, Phillips Atomics. He’s sent to the Moon to investigate a murder and soon finds himself swept up in a plot involving gangsters, a scientist, and his (of course) lovely daughter. Set in a mythical post-WWII world where space travel and lunar colonies came to pass, it has a good hardboiled atmosphere, and plenty of whiz-bang chrome-plated-rocketship details.

Last month I posted here about

Last month I posted here about