Birthday Reviews: W.E.B. Du Bois’s “Jesus Christ in Texas”

|

|

|

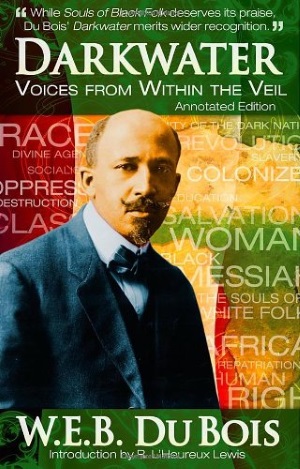

W.E.B. (William Edward Burghardt) Du Bois was born on February 23, 1868 and died on August 27, 1963. He was the first black man to earn a doctorate from Harvard University and taught history, sociology, and economics.

Du Bois helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1909. Most of W.E.B. Du Bois’s writings were sociological in nature, focusing on the plight of African-Americans. Throughout his career, he fought for equal rights for blacks and against lynchings and Jim Crow laws.

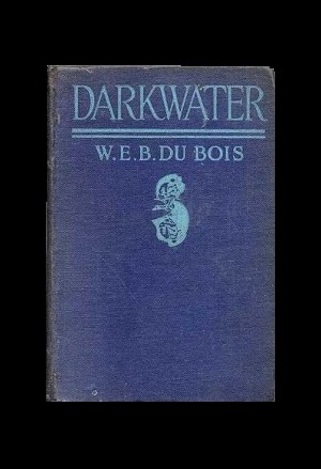

“Jesus Christ In Texas” was original published in Du Bois’s collection Darkwater: Voices from the Veil in 1920. It has been reprinted numerous times since.

Two of Du Bois’s stories have elements of the fantastic in them, including “Jesus in Texas.” As told in the title, this story is about a visitation of Jesus to Texas. During his brief time, he sees black prisoners used on a chain gang, the whites who are benefiting from their labor, and a prisoner who has escaped.