Fantasia 2019, Day 9, Part 1: It Comes

On the evening of July 19 I sat down in the Hall Theatre for a screening of It Comes (Kuru, 来る), a Japanese horror film. Directed by Tetsuya Nakashima, it’s based on the novel Bogiwan ga kuru, by Ichi Sawamura, with a screenplay by Nakashima, Hideto Iwai, and Nobuhiro Monma. It’s clever and colourful, and at two and a half hours it’s also a sprawling film that justifies its length by twisting in ways you don’t expect. It’s also a success, an entertaining and occasionally chilling movie that builds a universe without being too detailed about the supernatural horror lurking beyond consensus reality.

On the evening of July 19 I sat down in the Hall Theatre for a screening of It Comes (Kuru, 来る), a Japanese horror film. Directed by Tetsuya Nakashima, it’s based on the novel Bogiwan ga kuru, by Ichi Sawamura, with a screenplay by Nakashima, Hideto Iwai, and Nobuhiro Monma. It’s clever and colourful, and at two and a half hours it’s also a sprawling film that justifies its length by twisting in ways you don’t expect. It’s also a success, an entertaining and occasionally chilling movie that builds a universe without being too detailed about the supernatural horror lurking beyond consensus reality.

After a mysterious intro, the film starts with Hideki (Satoshi Tsumabuki) and Kana (Haru Kuroki), an apparently perfect young couple. Various bits of supernatural foreshadowing lead to the birth of their baby girl, Chisa, and Hideki throws himself into becoming the perfect father. But forces from his past are gathering, targeting Chisa. A friend, a professor of folklore named Tsuga (Munetaka Aoki, the Rurouni Kenshin movies) brings him to a disreputable writer, Nozaki (Jun’ichi Okada, Library Wars), and his spirit-medium girlfriend Makoto (Nana Komatsu, Jojo’s Bizarre Adventures). But will even they be enough to stop the evil coming for Hideki and Chisa?

This all just hints at the complexities of the plot, best experienced unspoiled. It Comes is an incredibly well-structured and well-paced movie that builds through a good collection of horror set-pieces and quieter character-driven moments to a stunning large-scale climax boasting one of the most fascinating examples of religious syncretism I’ve seen on film. At the very end, it has one of the most charming visual moments I’ve ever seen to indicate that the supernatural’s been thoroughly dealt with.

It is important that it be so well-crafted, I think, because as it builds it goes to some very strange places. The colours are lurid, slowly growing more so. And the film does not hesitate to increasingly explore genre as the film goes on, as well; Hideki and Kana are more-or-less real people when we meet them, and then Tsuga is a perhaps little more than real, and then Nozkaki and Makoto more than that, and then when we meet Makoto’s sister Kotoko we meet a character on another level of genre reality. And yet the tones work. The operatic feel of the high genre strangeness is fused to the everdayness of the young parents. And the story of the baby facing possession is given a weird grandeur by the surreal witchery that must be enlisted to fight the bogeyman threatening the child.

My last film of July 18 was in the big Hall Theatre. Knives and Skin was written and directed by Jennifer Reeder, and begins as a girl dies a violent death in a small midwestern town. In the wake of her disappearance secrets begin to come to light, and tensions rise among both her classmates and the adults. The movie proceeds to explore the town and its inhabitants in a series of sometimes-linked vignettes.

My last film of July 18 was in the big Hall Theatre. Knives and Skin was written and directed by Jennifer Reeder, and begins as a girl dies a violent death in a small midwestern town. In the wake of her disappearance secrets begin to come to light, and tensions rise among both her classmates and the adults. The movie proceeds to explore the town and its inhabitants in a series of sometimes-linked vignettes. Before my second film of July 18, a surreal science-fiction movie from the director of

Before my second film of July 18, a surreal science-fiction movie from the director of  I expected my last film of July 16 would be a documentary called Blood & Flesh – The Reel Life and Ghastly Death of Al Adamson. You may not have heard of Adamson. I hadn’t. He was an exploitation filmmaker in the 1960s and 70s, responsible for titles like Satan’s Sadists, The Naughty Stewardesses, and Dracula Vs. Frankenstein, as well as not one but two separate films titled Psycho a Go-Go (Technically, one was Psycho à Go-Go; note accent). Introducing the documentary, Fantasia co-Director Mitch Davis described Adamson as more of a hustler than a filmmaker, then called up director David Gregory to briefly explain the film’s genesis. Gregory said it began as a special feature for a Blu-ray release, but the more he investigated Adamson, the more he realised the material was worth digging into more deeply. Thus, it’s now a feature, covering Adamson’s life, the films he made, and his awful death.

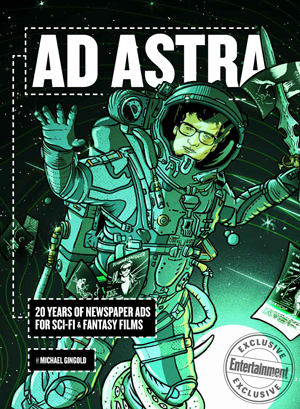

I expected my last film of July 16 would be a documentary called Blood & Flesh – The Reel Life and Ghastly Death of Al Adamson. You may not have heard of Adamson. I hadn’t. He was an exploitation filmmaker in the 1960s and 70s, responsible for titles like Satan’s Sadists, The Naughty Stewardesses, and Dracula Vs. Frankenstein, as well as not one but two separate films titled Psycho a Go-Go (Technically, one was Psycho à Go-Go; note accent). Introducing the documentary, Fantasia co-Director Mitch Davis described Adamson as more of a hustler than a filmmaker, then called up director David Gregory to briefly explain the film’s genesis. Gregory said it began as a special feature for a Blu-ray release, but the more he investigated Adamson, the more he realised the material was worth digging into more deeply. Thus, it’s now a feature, covering Adamson’s life, the films he made, and his awful death. On July 16 I started my day at Fantasia with a book launch. Michael Gingold’s book Ad Astra is coming out this fall, but attendees of his multimedia presentation had the chance to buy it earlier. It’s a follow-up to 2018’s Ad Nauseam: Newsprint Nightmares From the 1980s and its sequel to come in September, Ad Nauseam II: Newsprint Nightmares From the 1990s and 2000s. Those books were collections of classic newspaper ads for horror movies, while Ad Astra is subtitled 20 Years of Newspaper Ads for Sci-Fi & Fantasy Films.

On July 16 I started my day at Fantasia with a book launch. Michael Gingold’s book Ad Astra is coming out this fall, but attendees of his multimedia presentation had the chance to buy it earlier. It’s a follow-up to 2018’s Ad Nauseam: Newsprint Nightmares From the 1980s and its sequel to come in September, Ad Nauseam II: Newsprint Nightmares From the 1990s and 2000s. Those books were collections of classic newspaper ads for horror movies, while Ad Astra is subtitled 20 Years of Newspaper Ads for Sci-Fi & Fantasy Films. The fourth and last movie I saw on July 16 was the most experimental movie I’d seen at Fantasia, not only this year but possibly in all the time I’ve been going to the festival. Before that feature, though, was a short almost as strange.

The fourth and last movie I saw on July 16 was the most experimental movie I’d seen at Fantasia, not only this year but possibly in all the time I’ve been going to the festival. Before that feature, though, was a short almost as strange.

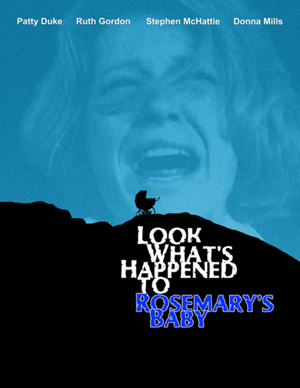

It’s relatively unusual for me to watch a movie that I know going in is not good. But every so often, and usually at Fantasia, something bizarre comes along that looks bad but also in its way promising. So it was that for my third film of July 16 I settled in at the De Sève Theatre for a screening of the rare 1976 TV-movie sequel to Rosemary’s Baby: an opus directed by Sam O’Steen titled Look What’s Happened to Rosemary’s Baby. Star Stephen McHattie was in attendance, and would stick around to take our questions after the film.

It’s relatively unusual for me to watch a movie that I know going in is not good. But every so often, and usually at Fantasia, something bizarre comes along that looks bad but also in its way promising. So it was that for my third film of July 16 I settled in at the De Sève Theatre for a screening of the rare 1976 TV-movie sequel to Rosemary’s Baby: an opus directed by Sam O’Steen titled Look What’s Happened to Rosemary’s Baby. Star Stephen McHattie was in attendance, and would stick around to take our questions after the film. For my second movie of July 15 I went to the Fantasia screening room to watch the Cambodian film The Prey. Directed by Jimmy Henderson from a script by Henderson with Michael Hodgson and Kai Miller, this is a film that traces its narrative lineage back to Richard Connell’s immortal “The Most Dangerous Game.” In this case, the game’s played in the wilds of Cambodia, and the rules turn out to be surprisingly complex — and the number of players surprisingly large.

For my second movie of July 15 I went to the Fantasia screening room to watch the Cambodian film The Prey. Directed by Jimmy Henderson from a script by Henderson with Michael Hodgson and Kai Miller, this is a film that traces its narrative lineage back to Richard Connell’s immortal “The Most Dangerous Game.” In this case, the game’s played in the wilds of Cambodia, and the rules turn out to be surprisingly complex — and the number of players surprisingly large.