“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

(Gat — Prohibition Era term for a gun. Shortened version of Gatling Gun)

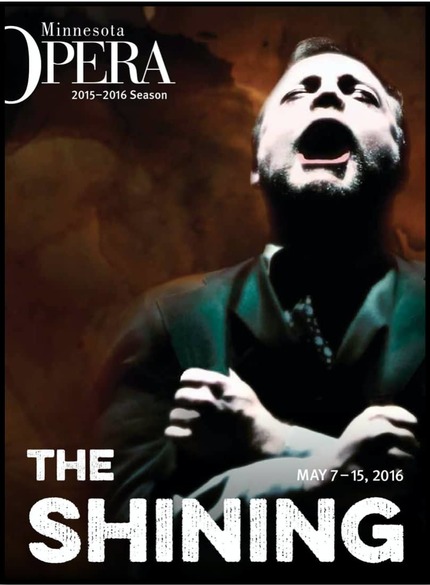

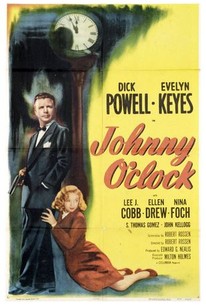

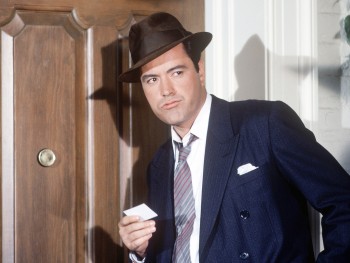

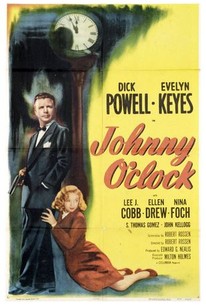

And for the third year in a row, A (Black) Gat in the Hand makes a hardboiled reservation for Monday mornings. It’s a limited run, but for the month of June, I’ll look at some hardboiled/noir on screen efforts: Ones that you might not be quite as familiar with. Not totally off the beaten path, but not the big names, either. And we kick things off with Dick Powell’s follow up to Murder My Sweet, Johnny, O’Clock.

When you think of the hardboiled movie, or book, it’s usually a private eye that comes to mind. There’s Sam Spade, and Philip Marlowe, and Mike Hammer. Of course, there were also cops in movies, like Glenn Ford’s Dave Bannion in The Big Heat; and Frederick Nebel’s MacBride in print. Those stories were changed into seven Torchy Blaine movies, and quite different from Nebel’s hardboiled stories about MacBride, unfortunately.

Other occupations were covered, including reporters, and lawyers. Ex-soldiers of various stripes, like Alan Ladd in The Blue Dahlia, were popular. A movie that I really like in this genre starred a gambler. Like Humphrey Bogart’s Dead Reckoning, this film doesn’t appear on any top ten lists, but it doesn’t feature a private eye, and it’s a ‘could have been really good’ film.

Like James Cagney and George Raft, Dick Powell was a successful song and dance man in Hollywood. Then, he was surprisingly cast as Raymond Chandler’s world-weary Phililp Marlowe in Murder My Sweet, and he nailed the part. That 1944 effort was the first of four hardboiled films he made in a five-movie span, of which Johnny O’Clock was the third.

Picking Iron (trivia) – This new side of Powell made him perfect for the singing, funny, tough radio PI, Richard Diamond (I love that series).

Powell plays the title character, and he’s manager of a fancy (and legal) gambling joint in NYC. He dresses well, knows lots of people, and lives in a fancy apartment with an ex-con named Charlie, who is his jack of all trades assistant.

…

Read More Read More

Do you remember your first hero? Any kind of hero. It could have been a hero from a movie or a book or a television show, even a hero from real life.

Do you remember your first hero? Any kind of hero. It could have been a hero from a movie or a book or a television show, even a hero from real life.