Fantasia 2020, Part IV: The Undertaker’s Home

As part of the unusual nature of this year’s Fantasia, the festival organisers set up many more non-film special events than usual. Each day boasts a presentation, panel discussion, or other streamed activity, all of them to be archived on the festival’s YouTube page (in fact the organisers have just announced they’ll host a conversation between Jay Baruchel and Finn Wolfhard on August 29). Friday, August 21, began with a presentation by critic and author Carolyn Mauricette of “Afrofuturism: Visions Of the Future From ‘The Other’ Side.” It was a fascinating hour-long talk about Black creators and their work. Rather than focus on themes or analyse individual accomplishments, Mauricette gave a brief introduction about mass media views of Blackness and then positioned Afrofuturism as an alternative reality, listing artists in various fields, and indeed mentioning alternatives to Afrofuturism such as filmmaker Wanuri Kahiu’s Afrobubblegum. You can find the entire presentation here.

As part of the unusual nature of this year’s Fantasia, the festival organisers set up many more non-film special events than usual. Each day boasts a presentation, panel discussion, or other streamed activity, all of them to be archived on the festival’s YouTube page (in fact the organisers have just announced they’ll host a conversation between Jay Baruchel and Finn Wolfhard on August 29). Friday, August 21, began with a presentation by critic and author Carolyn Mauricette of “Afrofuturism: Visions Of the Future From ‘The Other’ Side.” It was a fascinating hour-long talk about Black creators and their work. Rather than focus on themes or analyse individual accomplishments, Mauricette gave a brief introduction about mass media views of Blackness and then positioned Afrofuturism as an alternative reality, listing artists in various fields, and indeed mentioning alternatives to Afrofuturism such as filmmaker Wanuri Kahiu’s Afrobubblegum. You can find the entire presentation here.

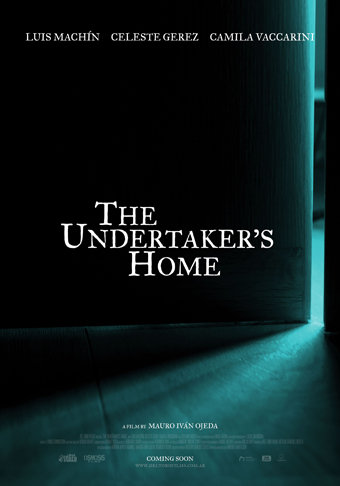

After that, I planned to watch the Argentinian horror film The Undertaker’s Home. Bundled with the feature came a short, “Abracitos,” directed by Tony Morales and written by Morales with Fer Zaragoza. The 11-minute Spanish short is a deeply atmospheric tale of two girls (Beatriz and Carmen Salas) alone at night, fearing a monster beyond the walls of the younger girl’s make-believe castle. It’s extremely well shot, evoking nonspecific fears of childhood, effectively setting up a monster without giving us details. It’s a strong minimalist piece that works on the imagination, and builds nicely to a crescendo of terror.

The Undertaker’s Home (La Funeraria) was written and directed by Mauro Iván Ojeda. It begins, appropriately, with a house, through which the camera glides in the middle of the night. That’s an effective way of showing us a bit about the people who live there: Bernardo (Luis Machín), the aging undertaker; Estela (Celeste Gerez), his young wife; and Irina (Camila Vaccarini), Estela’s daughter by a previous marriage. We also start to get a sense of the uncanny tied to the place. And the next morning there’s a more concrete image of strange goings-on: outside the house, everything to one side of a red line drawn along the ground looks as though a storm had hit. On the house’s side of the line, everything’s normal.

We soon learn that the family is under a kind of siege by the spirits of the dead, which might include the spirit of Irina’s dead father — who Estela claims was physically abusive to her. Irina’s not happy about living under siege, and about the rules the family has to follow. Estela’s not happy either, but wants to stay with Bernardo. Who himself seems to be strangely attracted to one of the invisible spirits. Slowly, we come to understand the strange situation, and the stresses the family’s under. And then new complications emerge, and we are shown that not everything is as we thought, both in the world of the dead and the world of the living family.

My first scheduled film at Fantasia 2020 was Special Actors (Supesharu Akutâzu, スペシャルアクターズ), written and directed by Shinichiro Ueda. I loved Ueda’s previous film, 2018’s One Cut of the Dead (Kamera wo tomeruna!, カメラを止めるな!), and this is his first solo feature since; he co-directed 2019’s Aesop’s Game (Isoppu no Omou Tsubo, イソップの思うツボ), and this year

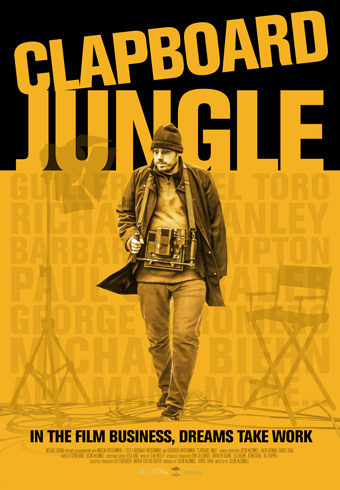

My first scheduled film at Fantasia 2020 was Special Actors (Supesharu Akutâzu, スペシャルアクターズ), written and directed by Shinichiro Ueda. I loved Ueda’s previous film, 2018’s One Cut of the Dead (Kamera wo tomeruna!, カメラを止めるな!), and this is his first solo feature since; he co-directed 2019’s Aesop’s Game (Isoppu no Omou Tsubo, イソップの思うツボ), and this year  Most of the movies I want to see at Fantasia 2020 play at a scheduled time, but quite a few are available on demand for the next two weeks. One of those struck me as a good place to start this year’s unusual Fantasia-from-home: Justin McConnell’s documentary Clapboard Jungle. It’s about the process of putting a film together, focussing not so much on the technical details of directing but the much longer struggle to find financing.

Most of the movies I want to see at Fantasia 2020 play at a scheduled time, but quite a few are available on demand for the next two weeks. One of those struck me as a good place to start this year’s unusual Fantasia-from-home: Justin McConnell’s documentary Clapboard Jungle. It’s about the process of putting a film together, focussing not so much on the technical details of directing but the much longer struggle to find financing.

Usually by this point in the year I’ve begun posting reviews of films I saw earlier in the summer at Montreal’s Fantasia International Film Festival. Here as elsewhere, things are different in 2020. When the coronavirus pandemic hit, Fantasia was postponed to the end of August. It looked like this year’s Festival was in danger of not happening at all. But the wonderful and dedicated people behind Fantasia have made it work;

Usually by this point in the year I’ve begun posting reviews of films I saw earlier in the summer at Montreal’s Fantasia International Film Festival. Here as elsewhere, things are different in 2020. When the coronavirus pandemic hit, Fantasia was postponed to the end of August. It looked like this year’s Festival was in danger of not happening at all. But the wonderful and dedicated people behind Fantasia have made it work;