Fantasia 2019, Day 19, Part 3: “A Japanese Boy Who Draws” and Yutaka Yamamoto’s Twilight

My third screening on July 29 was a double-feature at the De Sève Cinema of two animated movies, a long short and a short feature. “A Japanese Boy Who Draws” (ある日本の絵描き少年) is 20 minutes long. Twilight, which I immediately came to think of as (Not That) Twilight (and in fact some places online translate the title 薄暮, Hakubo, as Project Twilight), is 53 minutes long. They’re both slice-of-life films about young people in Japan making art, but are otherwise very different narratively and visually. Which is to say they have enough in common and enough contrast to make a fine double bill.

My third screening on July 29 was a double-feature at the De Sève Cinema of two animated movies, a long short and a short feature. “A Japanese Boy Who Draws” (ある日本の絵描き少年) is 20 minutes long. Twilight, which I immediately came to think of as (Not That) Twilight (and in fact some places online translate the title 薄暮, Hakubo, as Project Twilight), is 53 minutes long. They’re both slice-of-life films about young people in Japan making art, but are otherwise very different narratively and visually. Which is to say they have enough in common and enough contrast to make a fine double bill.

Written and directed by Masanao Kawajiri, “A Japanese Boy Who Draws” can actually be said to deal with two Japanese boys who draw: Shinji, an aspiring manga artist, and his friend Masaru, a mentally challenged boy who wears a luchador mask everywhere. They meet at the age of 10, and we follow Shinji as he narrates his career trying to break into manga. He breaks from Masaru, who does not grow up as Shinji does. But Shinji’s life doesn’t go as smoothly as he hoped. He gets into manga, he gets better at his craft, but nevertheless his career stalls out. He returns to his home town, and, as one might expect, reconnects with Masaru in a surprising way.

Put like that, the film sounds standard; it isn’t. It looks distinctive, to start with. Different art styles reflect Shinji’s different ages, different levels of drawing ability, and perhaps different relationships to art at different times. Childlike drawings give way to manga pages give way to greyscale live-action photography. The film’s particularly strong technically in the way it uses comics pages to tell its story; panels are a tricky thing to make work in motion pictures, but it comes off brilliantly here.

At the same time, this isn’t just a technical exercise. There’s some powerful emotional material in the movie. Shinji’s lack of progress in his career is powerful because it feels almost subversive: he works hard, he lives for his art, and he gets nowhere not just in business but as an artist. If there is a problem with the film, incidentally, it is that it may be difficult for an audience to assess how good an artist Shinji is or is not. I found myself surprised at the way other characters uniformly dismissed his work when the art on screen seemed perfectly fine. In any event, Shinji doesn’t have the creativity needed to make a great manga, it seems, which is fair enough.

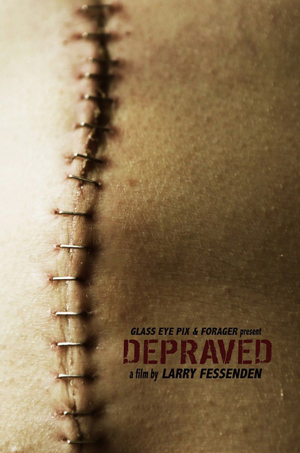

One of the things that most fascinates me about film is the way Frankenstein is at least as important in that medium as it is in prose. Obviously this importance is most visible in genre film, but it’s there one way or another in the mainstream too — consider Gods and Monsters. From at least 1910, when the story was adapted into a then-epic ten-minute movie, through the tremendously important 1931 Boris Karloff version, it’s a story that’s haunted cinema. One way or another the tale or the monster comes up regularly at Fantasia, whether in Guillermo del Toro

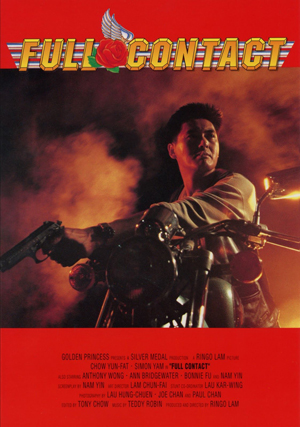

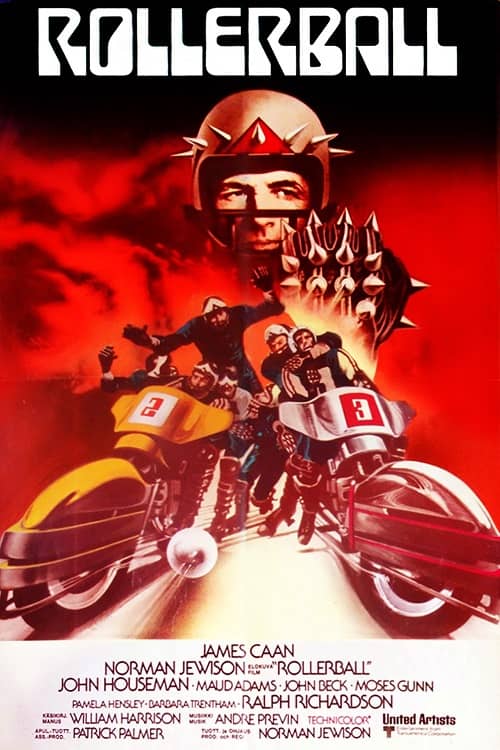

One of the things that most fascinates me about film is the way Frankenstein is at least as important in that medium as it is in prose. Obviously this importance is most visible in genre film, but it’s there one way or another in the mainstream too — consider Gods and Monsters. From at least 1910, when the story was adapted into a then-epic ten-minute movie, through the tremendously important 1931 Boris Karloff version, it’s a story that’s haunted cinema. One way or another the tale or the monster comes up regularly at Fantasia, whether in Guillermo del Toro  There’s still so much I don’t know about film, so many great movies I haven’t seen. Thankfully, every year Fantasia screens restorations and special presentations of a number of established classics (and semi-classics). I usually don’t have free time in my schedule to watch films I’ve already seen — I had to pass on First Blood to watch

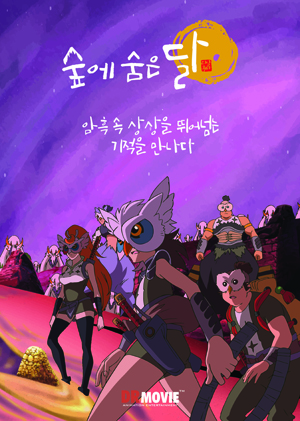

There’s still so much I don’t know about film, so many great movies I haven’t seen. Thankfully, every year Fantasia screens restorations and special presentations of a number of established classics (and semi-classics). I usually don’t have free time in my schedule to watch films I’ve already seen — I had to pass on First Blood to watch  My second film of July 28 screened at the De Sève Cinema. It was an animated film from Korea with a Japanese director, Takahiro Umehara, and it was stunning. Watching early scenes of The Moon in the Hidden Woods (Sup-e Sum-eun Dal, 숲에 숨은 달) I wondered where the movie could go from its opening act — it had already shown us a major city, fights, desert nomads, monsters, a wild variety of costumes and architecture and technologies and designs. Surely, I thought, it would have to slow down. It did; and then built back up again.

My second film of July 28 screened at the De Sève Cinema. It was an animated film from Korea with a Japanese director, Takahiro Umehara, and it was stunning. Watching early scenes of The Moon in the Hidden Woods (Sup-e Sum-eun Dal, 숲에 숨은 달) I wondered where the movie could go from its opening act — it had already shown us a major city, fights, desert nomads, monsters, a wild variety of costumes and architecture and technologies and designs. Surely, I thought, it would have to slow down. It did; and then built back up again.

My first movie on July 28 was one of my most-anticipated of the festival. In 2017 I watched

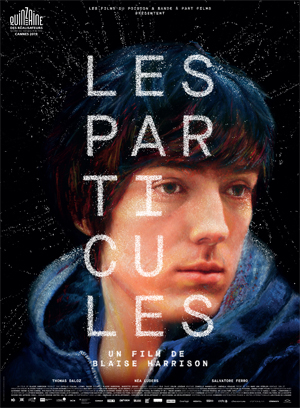

My first movie on July 28 was one of my most-anticipated of the festival. In 2017 I watched  For my last movie of July 27 I crossed the street to the De Sève Cinema to take in the French-Swiss co-production Les Particules (The Particles). It’s the first fiction feature by director Blaise Harrison, who co-wrote the script with Mariette Désert. After a day of particularly frenetic movies, this was good way to end the evening; a subtler, atmospheric, intelligent, and character-based film that thoroughly succeeded at what it was trying to do.

For my last movie of July 27 I crossed the street to the De Sève Cinema to take in the French-Swiss co-production Les Particules (The Particles). It’s the first fiction feature by director Blaise Harrison, who co-wrote the script with Mariette Désert. After a day of particularly frenetic movies, this was good way to end the evening; a subtler, atmospheric, intelligent, and character-based film that thoroughly succeeded at what it was trying to do. My fourth film of July 27 was once again in the Hall Theatre. It was a Russian film about which I had heard very good things, with one web site calling it among the best action movies of the year so far. You may have heard of Chekhov’s gun; well, Why Don’t You Just Die! (Papa, Sdokhni) gives us Chekhov’s gun, along with Chekhov’s other gun, Chekhov’s claw hammer, Chekhov’s power drill, Chekhov’s CRT TV, and any number of Chekhov’s other odds and ends.

My fourth film of July 27 was once again in the Hall Theatre. It was a Russian film about which I had heard very good things, with one web site calling it among the best action movies of the year so far. You may have heard of Chekhov’s gun; well, Why Don’t You Just Die! (Papa, Sdokhni) gives us Chekhov’s gun, along with Chekhov’s other gun, Chekhov’s claw hammer, Chekhov’s power drill, Chekhov’s CRT TV, and any number of Chekhov’s other odds and ends.  My third movie of July 27 was a live-action manga adaptation by the dauntless and prolific

My third movie of July 27 was a live-action manga adaptation by the dauntless and prolific  For my second film of July 27 I stuck around the Hall Theatre for another animated feature, this time from Japan. Preceding it was a 13-minute animated short from Canada.

For my second film of July 27 I stuck around the Hall Theatre for another animated feature, this time from Japan. Preceding it was a 13-minute animated short from Canada.