The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes: At the Movies with Basil (Rathbone)

I started writing a regular column for Black Gate in March of 2014. I’ve covered a lot of ground, but today we’re going to try something new. Earlier this year, I was watching Casablanca (yet AGAIN) on TCM, and I decided to do do a running commentary about it on my FB page. I know a LOT about that movie. TCM showed it again a little over a month later, so I did it again. It was fun.

I started writing a regular column for Black Gate in March of 2014. I’ve covered a lot of ground, but today we’re going to try something new. Earlier this year, I was watching Casablanca (yet AGAIN) on TCM, and I decided to do do a running commentary about it on my FB page. I know a LOT about that movie. TCM showed it again a little over a month later, so I did it again. It was fun.

I decided to do the same thing with a Basil Rathbone Sherlock Holmes movie. But I watched it on Youtube, which let me pause it while I typed comments, and took screenshots. That worked satisfactorily. During Casablanca, I was so busy (mis)typing comments, I missed half of the movie.

So, this is a mix of my running commentary, with more information and fun stuff added in during composition of the essay. It’s a hybrid, but not as detailed as I normally write. We’ll see how it goes as we look at two films: Terror By Night, and The Scarlet Claw. I already wrote a full post on the second movie. I just felt like watching it again.

Of course, all fourteen Holmes films starring Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce were black and white. But colorized versions, both official and not, have been around for a while. I watched colorized versions of both films, via Youtube. Terror By Night was done by TCC (Timeless Classics now in Color). They’ve got a bunch of movies on their website. And the quality of this one was excellent. The best colorized Holmes I’ve seen. The Scarlet Claw was by ATC, and it was muddy.

TERROR BY NIGHT

We start with number eleven of twelve in the Universal Pictures series. Only one more Holmes movie remained, as Rathbone, tired of being typecast, walked away from the franchise (and the associated radio show).

Critic Farah Mendlesohn introduced the term ‘portal fantasy’ in her 2008 book Rhetorics of Fantasy to describe stories in which a protagonist leaves their home and enters a new, larger, magical world. I’ve seen the term used often to refer to a specific subtype of these fantasies, in which a protagonist from conventional reality passes through a portal to a fictional realm and proceeds to quest about and have adventures. The rise of this more specific definition is not entirely surprising, given how common that kind of story is, perhaps especially with younger protagonists. Either sort of portal fantasy can present a character, confronted with a new and strange world, with an opportunity to grow and change. Or, instead, can be about reification of the character’s previous identity — a locking-in of who they are, after the success of a quest that aims to stop a bad change form occurring.

Critic Farah Mendlesohn introduced the term ‘portal fantasy’ in her 2008 book Rhetorics of Fantasy to describe stories in which a protagonist leaves their home and enters a new, larger, magical world. I’ve seen the term used often to refer to a specific subtype of these fantasies, in which a protagonist from conventional reality passes through a portal to a fictional realm and proceeds to quest about and have adventures. The rise of this more specific definition is not entirely surprising, given how common that kind of story is, perhaps especially with younger protagonists. Either sort of portal fantasy can present a character, confronted with a new and strange world, with an opportunity to grow and change. Or, instead, can be about reification of the character’s previous identity — a locking-in of who they are, after the success of a quest that aims to stop a bad change form occurring. The Fantasia Film Festival usually runs around three weeks, but 2020 and its myriad of challenges meant this year’s festival lasted only two-thirds of that. Time moves fast, faster still during Fantasia, and so it came about that with a sudden shock I found myself in the final hours. I had three on-demand movies still to watch that I hadn’t gotten to, and only one on a fixed schedule, my first of the last day.

The Fantasia Film Festival usually runs around three weeks, but 2020 and its myriad of challenges meant this year’s festival lasted only two-thirds of that. Time moves fast, faster still during Fantasia, and so it came about that with a sudden shock I found myself in the final hours. I had three on-demand movies still to watch that I hadn’t gotten to, and only one on a fixed schedule, my first of the last day. Science fiction has strong historical links to the adventure genre, but ideas-oriented science fiction tends to move away from adventure. Adventure fiction typically focusses on individual protagonists doing world-altering things, and a science fiction backdrop makes for a fictional world susceptible to alteration. But much actual social change is driven by organisations and groups, and science fiction that wants to talk about ideas usually acknowledges that. At the extreme you get something like Asimov’s early Foundation stories: tales in which the inevitable working-out of sociological forces are at the centre of the story, not the actions of a single hero. It’s not impossible to balance a quest-story about a single protagonist with a realistic portrayal of a world defined by its social structures, but tales that pull off both aspects are worth noting.

Science fiction has strong historical links to the adventure genre, but ideas-oriented science fiction tends to move away from adventure. Adventure fiction typically focusses on individual protagonists doing world-altering things, and a science fiction backdrop makes for a fictional world susceptible to alteration. But much actual social change is driven by organisations and groups, and science fiction that wants to talk about ideas usually acknowledges that. At the extreme you get something like Asimov’s early Foundation stories: tales in which the inevitable working-out of sociological forces are at the centre of the story, not the actions of a single hero. It’s not impossible to balance a quest-story about a single protagonist with a realistic portrayal of a world defined by its social structures, but tales that pull off both aspects are worth noting.

Yesterday I wrote about

Yesterday I wrote about  Macbeth is one of the earliest true horror stories, in the sense of a story whose main aim is to play with the emotion of fear, and there’s a notable comic-relief scene with a gatekeeper right after the first gruesome murder. That scene became the subject of a famous essay by Thomas de Quincey arguing (roughly) that the horror’s made greater by contrast. So from the point where horror first began to emerge as a genre, storytellers have been conscious of the effect that comes from balancing horror with the everyday, and even with the comedic.

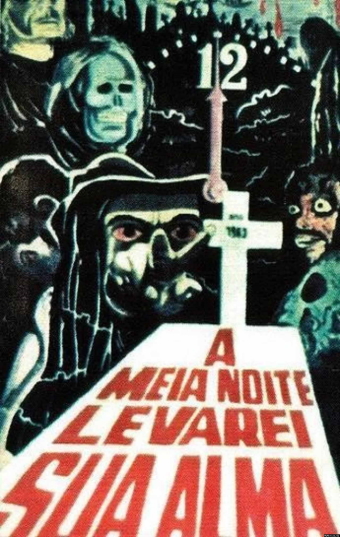

Macbeth is one of the earliest true horror stories, in the sense of a story whose main aim is to play with the emotion of fear, and there’s a notable comic-relief scene with a gatekeeper right after the first gruesome murder. That scene became the subject of a famous essay by Thomas de Quincey arguing (roughly) that the horror’s made greater by contrast. So from the point where horror first began to emerge as a genre, storytellers have been conscious of the effect that comes from balancing horror with the everyday, and even with the comedic. Brazilian director José Mojica Marins died earlier this year at the age of 83. He made low-budget films across a number of genres, with his horror work best known. His character Coffin Joe (Zé do Caixão), introduced in the 1963 film At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul (A Meia Noite eu Levarei sua Alma) is a kind of national ghoul of Brazil. Fantasia decided to honour Marins by making three of his films available on-demand through the festival, and scheduling a talk about Marins with his friend Dennison Ramalho on the last day of the festival;

Brazilian director José Mojica Marins died earlier this year at the age of 83. He made low-budget films across a number of genres, with his horror work best known. His character Coffin Joe (Zé do Caixão), introduced in the 1963 film At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul (A Meia Noite eu Levarei sua Alma) is a kind of national ghoul of Brazil. Fantasia decided to honour Marins by making three of his films available on-demand through the festival, and scheduling a talk about Marins with his friend Dennison Ramalho on the last day of the festival;