Ellsworth’s Cinema of Swords: Beyond Captain Blood: Three by Sabatini

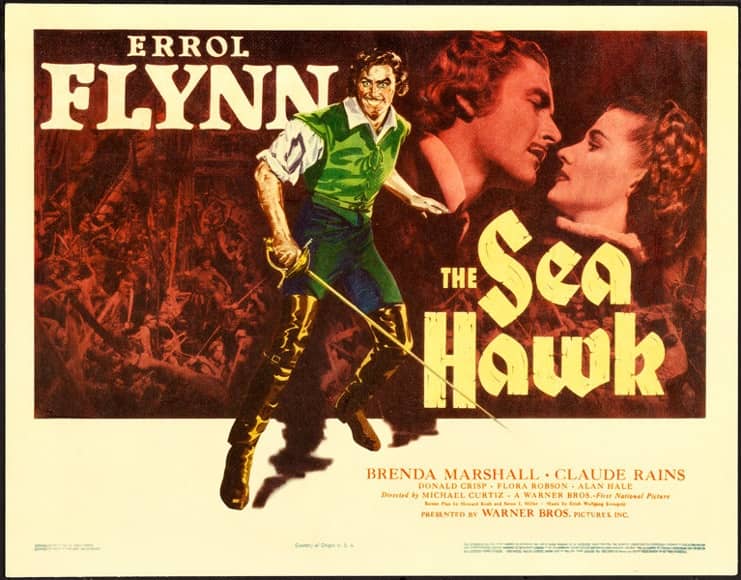

The Sea Hawk (Warner Bros, 1940)

We’ve already covered Errol Flynn’s breakthrough swashbuckler Captain Blood (1935) in this series, and you’ve probably seen and savored it, but you might not be familiar with Rafael Sabatini, the author who wrote the novel it was so memorably adapted from. In the Nineteenth Century Alexandre Dumas père was the king of historical adventure, but in the Twentieth Century that crown passed to Rafael Sabatini (1875-1950). Born in Italy, Sabatini was raised and schooled in Britain, Italy, and Switzerland, and was fluent in at least five languages. He settled in England in the early 1890s and in 1902 published The Suitors of Yvonne, the first of thirty-one historical novels, pretty much all of which can be classified as swashbucklers. In fact, in the early twentieth century the name Sabatini practically defined the genre. (He’s the only author who’s included twice in my Big Book of Swashbuckling Adventure anthology.)

Sabatini’s novels were perfect film fodder; a half-dozen of them made it to the screen in the silent era, and after the success of Flynn’s Captain Blood Hollywood revisited Sabatini’s backlist for another round in the forties and fifties. The three covered below are the best of the lot — and two of them are as good as it gets!

The Sea Hawk

Rating: ***** (Essential)

Origin: USA, 1940

Director: Michael Curtiz

Source: Warner Bros. DVD

Shortly after the success of Captain Blood (1935), Warner Bros. optioned Blood author Rafael Sabatini’s The Sea Hawk as a follow-up vehicle for Errol Flynn; but production was postponed, partly because the plot of Hawk was too similar to that of Blood. Several years passed, war between Britain and Germany began to appear inevitable, and the British production of Fire Over England (1937) provided a model for an American approach to the same historical events.

Last year I almost reviewed a movie at Fantasia called 1BR. But exhaustion got to me as the festival wore on, and I passed on the film. I’m never happy about having to compromise with fatigue, though, and since 1BR recently came to Netflix — where for a while it was among their 10 most-streamed movies, at one point even reaching the top 5 — I decided to rectify last year’s omission and take a look at it now.

Last year I almost reviewed a movie at Fantasia called 1BR. But exhaustion got to me as the festival wore on, and I passed on the film. I’m never happy about having to compromise with fatigue, though, and since 1BR recently came to Netflix — where for a while it was among their 10 most-streamed movies, at one point even reaching the top 5 — I decided to rectify last year’s omission and take a look at it now.