Frankenstein and R. J. Myers’ Domination Fantasies

NOTE: The following article was first published on May 30, 2010. Thank you to John O’Neill for agreeing to reprint these early articles, so they are archived at Black Gate which has been my home for over 5 years and 250 articles now. Thank you to Deuce Richardson without whom I never would have found my way. Minor editorial changes have been made in some cases to the original text.

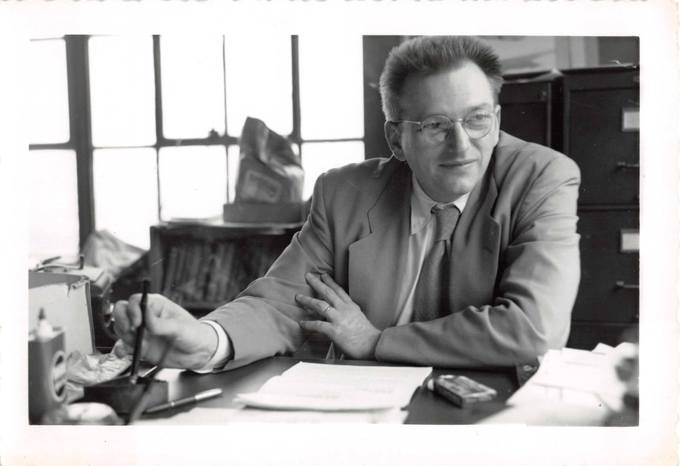

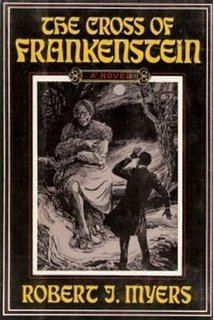

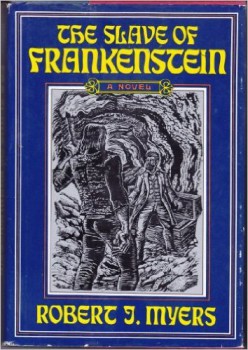

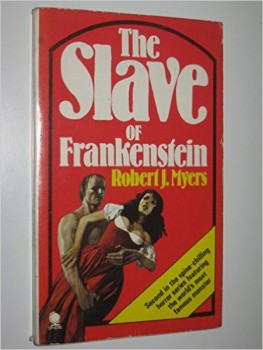

A couple weeks ago I reviewed R. J. Myers’ The Cross of Frankenstein. It was the respected political commentator’s first foray into fiction. He followed it with a sequel, 1976’s The Slave of Frankenstein and despite the promise of a third book, his only other genre efforts were a late seventies soft-core vampire title and a privately-published guide to blood-drinking as an alternative lifestyle.

A couple weeks ago I reviewed R. J. Myers’ The Cross of Frankenstein. It was the respected political commentator’s first foray into fiction. He followed it with a sequel, 1976’s The Slave of Frankenstein and despite the promise of a third book, his only other genre efforts were a late seventies soft-core vampire title and a privately-published guide to blood-drinking as an alternative lifestyle.

I always feel a pang of guilt when I come down hard on a fellow pastiche writer. I’ve been on the receiving end of disappointed Sax Rohmer and Conan Doyle fans who felt I had no business continuing the adventures of characters they love. At the same time, I believe I have been fair and honest in my assessments when reviewing pastiches. I have the utmost respect for Joe Gores, Michael Hardwick, Cay Van Ash, and Freda Warrington as writers who tried hard to stay true to the original author in terms of style and spirit. I can still enjoy Peter Tremayne and Basil Copper who, despite falling short of the mark, can still spin an entertaining yarn. Consequently, I feel justified when I confine Myers to the lowest pit of literary Hell alongside Ian Holt and Richard Jaccoma for The Slave of Frankenstein, while a very different beast than Myers’ first effort, is equally contemptible.