Unbound Worlds on a Century of Sword and Planet

|

|

|

Who doesn’t love Sword & Planet? No, don’t send me a bunch of declarative e-mail; it was a rhetorical question. Anyway, there’s only one kind of person who doesn’t love Sword & Planet: someone with no joy in their life.

But it’s perfectly okay to not know where to start. Despite celebrating its 100th birthday last year, Sword & Planet is not as popular as its sister genres (Sword & Sorcery, Sword & Six-Gun, Sword and Sandal, Sword & Sextant, Sword & Slupree….). And that’s okay, we love it just the same. But what is Sword & Planet? Matt Staggs does a fine job recapping the rich history of this venerable sub-genre at Unbound Worlds.

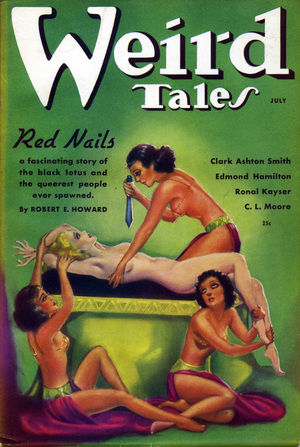

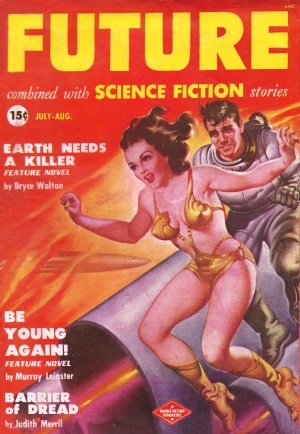

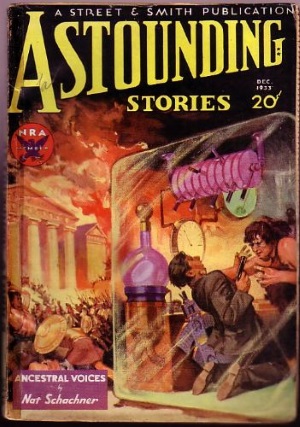

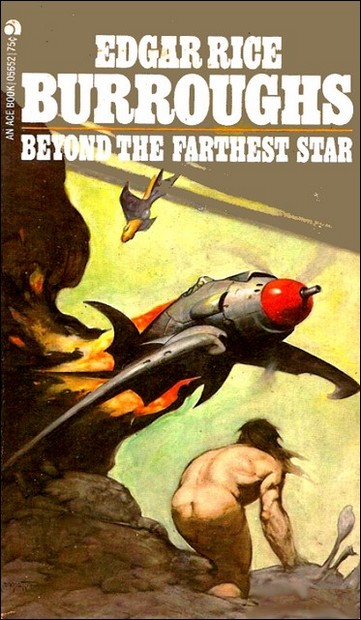

Mash together fantasy’s sword-swinging heroes, and the far-out alien civilizations of early science-fiction, and you’ve got Sword and Planet fiction. Arguably the brainchild of Tarzan creator Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sword and Planet tales usually features human protagonists adventuring on a planet teeming with life, intelligent or otherwise. Science takes a backseat to romance and derring-do… Where Sword and Planet can really be seen today is in the influence it has had on popular culture. The lightsabers, blasters, and planet-hopping heroics of Star Wars probably wouldn’t exist were it not for Sword and Planet. Neither would Avatar or Stargate.

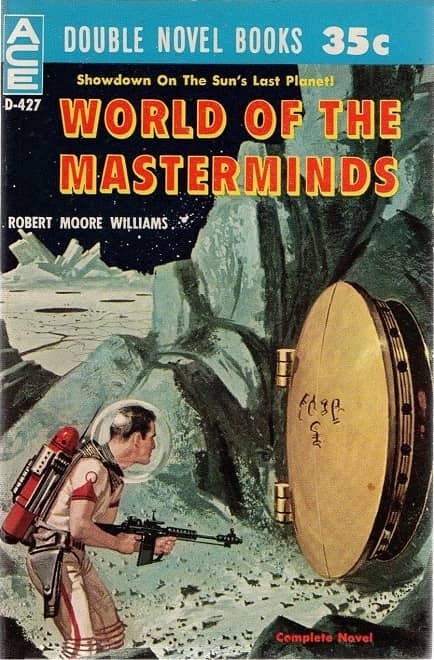

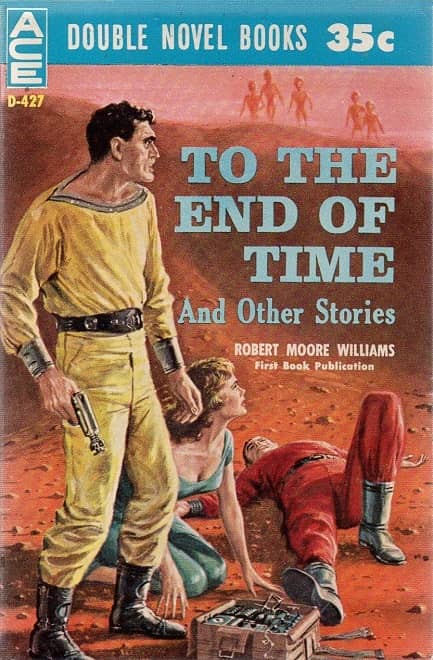

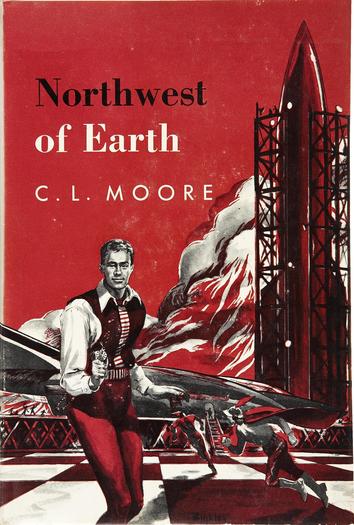

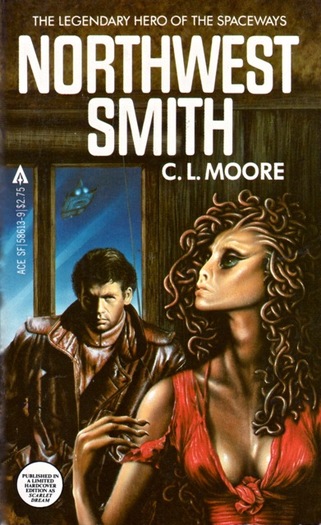

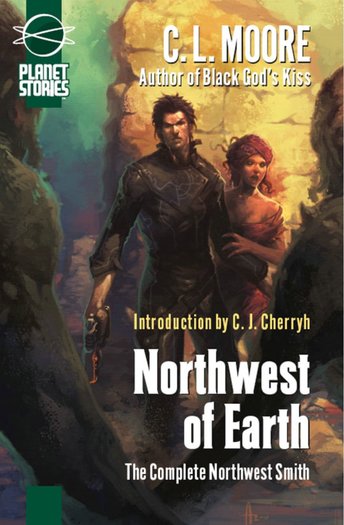

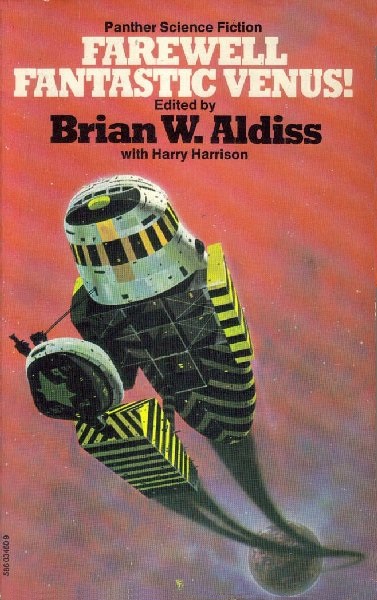

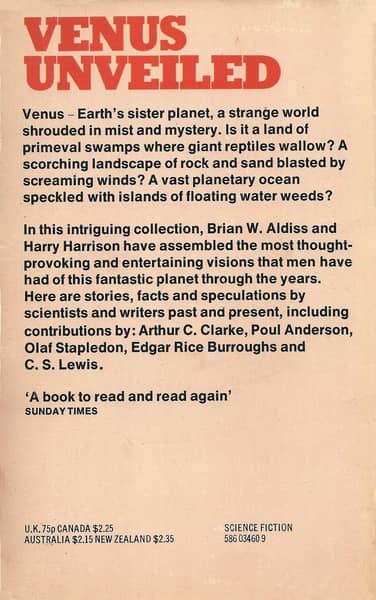

Interested? Matt also recommends some classic titles by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Jack Vance, Leigh Brackett, Kenneth Bulmer, Chris Roberson, and others. Here’s a few of his recs.