Birthday Reviews: Willard E. Hawkins’s “The Dwindling Sphere”

Willard E. Hawkins was born on September 27, 1887 and died on April 17, 1970.

Hawkins only published eleven short stories of genre interest over a span of nearly thirty years, although he published his first story as early as 1912. In addition to writing various genres, he established World Press, for which he was the publisher and editor of mostly non-fiction books about the West. He also worked as a newspaper editor for various Colorado papers, including Denver Times and the Rocky Mountain News. His first genre story, “The Dead Man’s Tale,” appeared in the debut issue of Weird Tales.

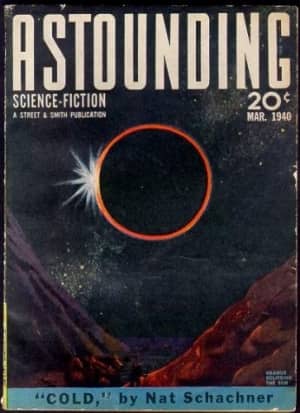

“The Dwindling Sphere” was originally published in the March 1940 issue of Astounding Science-Fiction, edited by John W. Campbell, Jr. Laurence Janiver reprinted it in his 1966 anthology Masters’ Choice (a.k.a. 18 Greatest Science Fiction Stories). The story was picked up by Isaac Asimov and Martin H. Greenberg for their anthology The Great Science Fiction Stories Volume 2: 1940 (a.k.a. Isaac Asimov Presents the Golden Years of Science Fiction), which caused it to be translated into German in 1980. In 2017, Hank Davis used the story in his anthology If This Goes Wrong…

Hawkins explores several generations of a single family in “The Dwindling Sphere.” The first section, set in 1945, discusses how Frank Baxter accidentally created the Plastocene process while attempting to find a way to create atomic energy. He was partially successful in creating a reaction, but the energy he was seeking completely dissipated, leaving behind a product which would revolutionize manufacturing. Subsequent sections focus on his descendants who discover Baxter’s journals and add on to them as they deal with the long-term repercussions of his discovery.

Hawkins deals with a society in which the working class has been turned into a luxury class since only a small number of people are needed to supply the world with plastocene, and therefore everything it needs, although food production hasn’t (yet) been switched to plastocene. In this period, the new luxury class is discovering that work provides them with a raison d’etre. Several hundred years later, society has evolved more and the early Baxters have been all but forgotten until a distant relation finds their diary, which corrects many historical misconceptions. By that time, plastocene production is beginning to threaten the livability of Earth, leading to the final sections of the story in which the Baxters’ descendants are forced off Earth by the long-term success of plastocene.