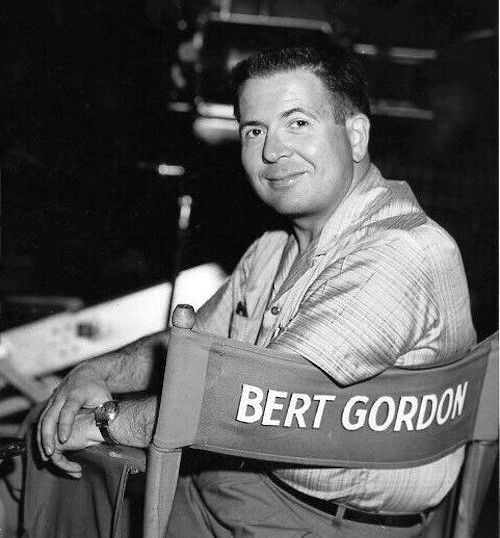

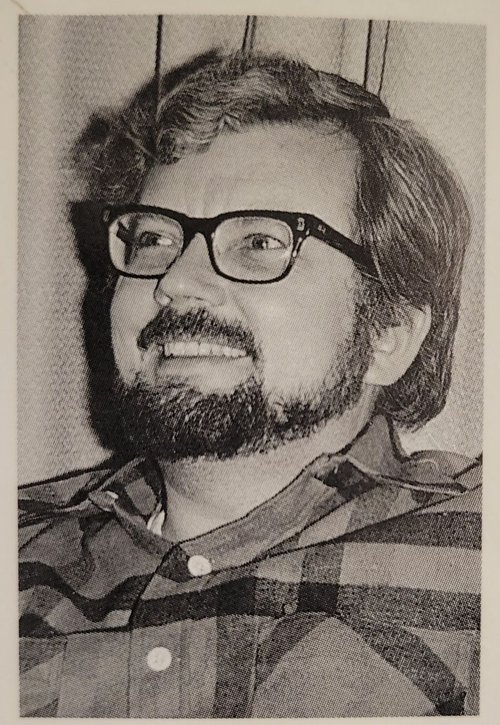

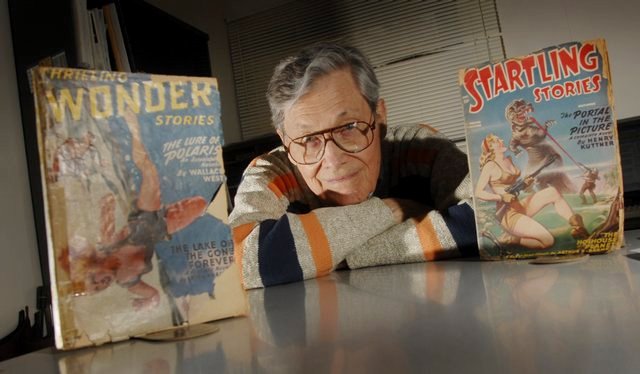

Joseph Wrzos, September 9, 1929 — April 7, 2023

|

|

|

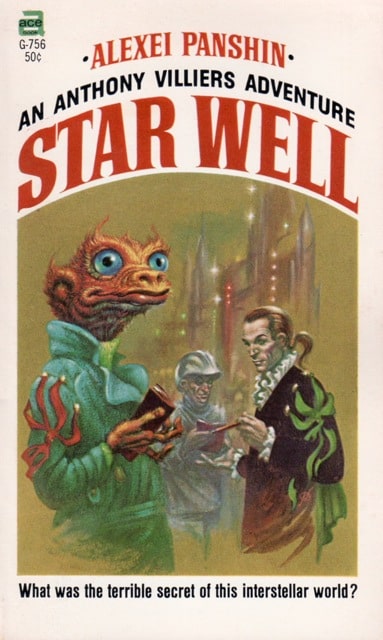

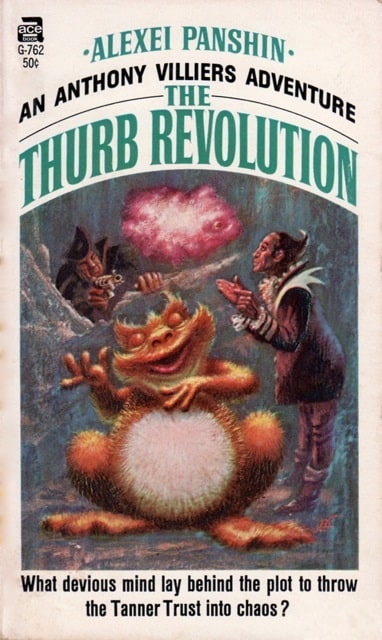

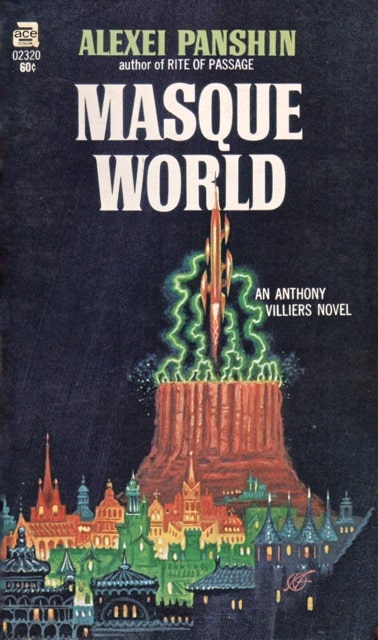

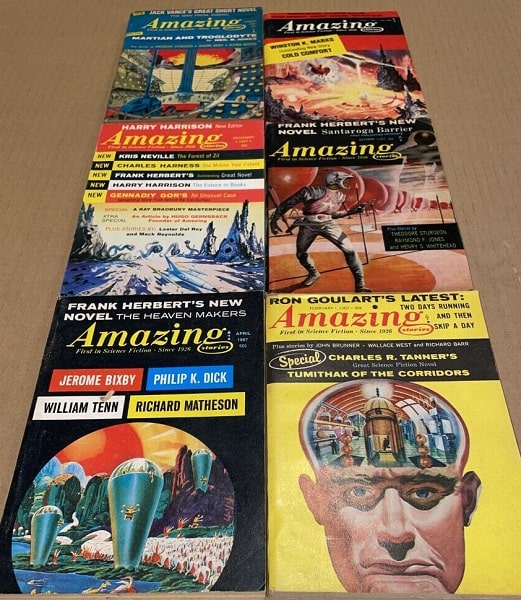

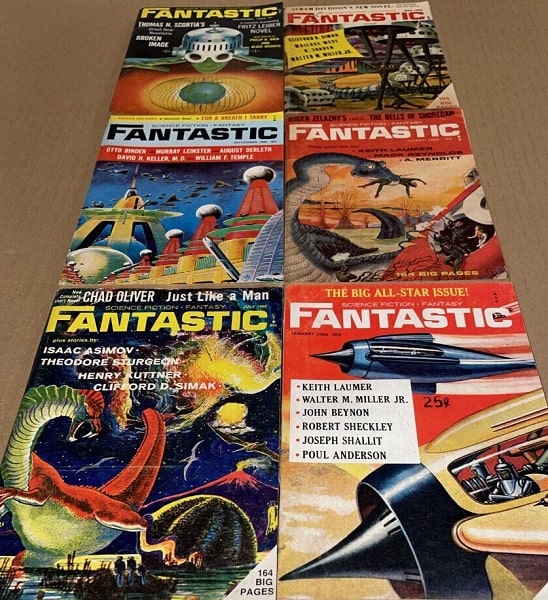

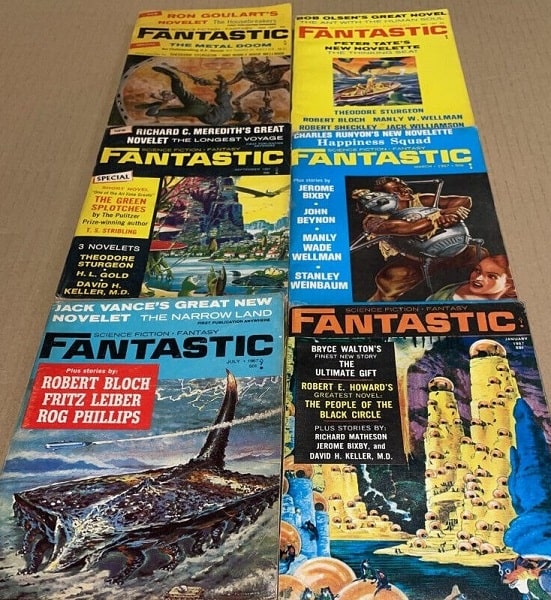

A few of the magazines edited by Joseph Wrzos: Amazing Stories

(complete year, 1967) and Fantastic Stories (complete years, 1966 & 1967)

I wanted to mention the passing on April 7, at the age of 93, of the former editor of Amazing and Fantastic, Joseph Wrzos, who used the name Joseph Ross professionally.

He was Cele Goldsmith Lalli’s immediate successor, and took over the magazines at a difficult time, when Ziff-Davis sold them to Ultimate Publishing. Lalli stayed with Ziff-Davis (and had a very successful career editing Modern Bride.) Ross worked under publisher Sol Cohen, who mandated severe budget cuts, including reprinting stories Amazing had first published decades before (and, until SFWA objected, not paying for them.)

Ross did his best in those circumstances, as far as I can tell, and was well liked by those who knew him. (I never met him myself.) In addition to his editing work (which included consulting for Arkham House, and for some later iterations of Amazing) he was a High School English teacher.