Birthday Reviews: Damien Broderick’s “Under the Moons of Venus”

Damien Broderick was born on April 22, 1944.

Broderick has won the Aurealis Award four times, for his short story “Infinite Monkey” and his novels The White Abacus, Transcension, and K-Machines. He has also won four Ditmar Awards, for his novels The Dreaming Dragon, White Abacus, Striped Holes, and the collection Earth Is But a Star. The Dreaming Dragon was also a John W. Campbell Memorial nominee and his story “This Wind Blowing, and This Tide” was one of two Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award nominations. In 2005, he received a Distinguished Scholarship from the IAFA and in 2010, he was awarded the A. Bertram Chandler Memorial Award.

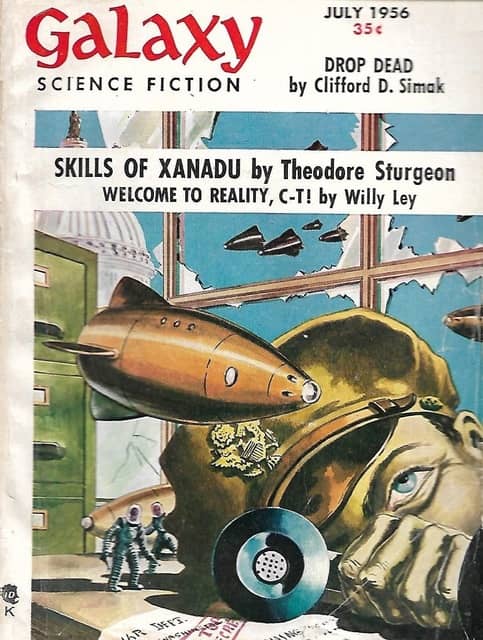

“Under the Moons of Venus” was originally published in Subterranean Online in the Spring 2010 issue, edited by Jonathan Strahan. Strahan included the story in his The Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year Volume 5 and it also appeared in David G. Hartwell and Kathryn Cramer’s Year’s Best SF 16, Rich Horton’s The Year’s Best Science Fiction 7 Fantasy 2011, Gardner Dozois’s The Year’s Best Science Fiction: Twenty-Eighth Annual Collection, and Allan Kaster’s audio anthology The Year’s Top Ten Tales of Science Fiction 3. Broderick included it in his 2012 collection Adrift in the Noösphere: Science Fiction Stories. The story was nominated for a Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award.

The title of Broderick’s “Under the Moons of Venus” evokes Edgar Rice Burroughs’s “Under the Moons of Mars,” the first Barsoom story, later reprinted as A Princess of Mars. The story itself, while it has elements that are reminiscent of John Carter’s exploits, is actually quite different, focusing its attention on Robert Blackett, who is wealthy in a seemingly depopulated world, working with a therapist, Clare Laing, who he is convinced is trying to seduce him, and consulting with his friend, Kafele Massri.