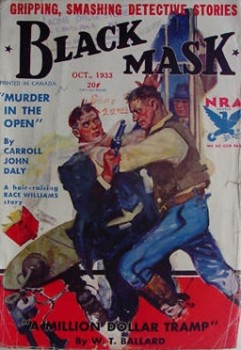

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask — October, 1933

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

(Gat — Prohibition Era term for a gun. Shortened version of Gatling Gun)

October of 1933 featured yet another solid issue of Black Mask under Joseph ‘Cap’ Shaw’s direction. The cover art was by J.W. Schlaiker, who had about fifty covers from 1929 to 1934. I don’t know why he abruptly stopped drawing for Black Mask. He served in France during World War I and was the War Department artist during World War II. He did portraits of Eisenhower, MacArthur and Patton.

With “Murder in the Open,” Race Williams made his forty-second appearance in Black Mask, dating back to June 1, 1923. For several years, Williams on the cover had guaranteed increased sales, but Carroll John Daly would be gone from Black Mask in just over a year and he was already regularly appearing in Dime Detective.

Daly was the first author to write in what became the hardboiled style with “Three Gun Terry” (which, of course, you read about here…) in the May 15, 1923 issue of Black Mask. Williams would follow in “Knights of the Open Palm in June, with Dashiell Hammett introducing his famous Continental Op in “Arson Plus” in October of that year. Daly’s writing style was far less polished and developed than Hammett’s, though I feel that it did improve over the years.

W(illiam) T(odhunter) Ballard was Nero Wolfe creator Rex Stout’s first cousin (which would explain why they shared such an unusual middle name). Ballard, who went on to become a very successful western author, wrote extensively for the detective pulps in the thirties and forties. He explained that he was struggling to sell to the lesser pulps when he saw The Maltese Falcon starring Ricardo Cortez. Hammett’s terse prose spoke to him and he bought an issue of Black Mask. He stayed up all night, wrote a story and sold it to the magazine. He would go on to a long career in the pulps and as a novelist.