Birthday Reviews: Daniel Abraham’s “Pagliacci’s Divorce”

Daniel Abraham was born on November 14, 1969.

Daniel Abraham won the International Horror Guild Award for his story “Flat Diane” in 2005. The story was also nominated for a Nebula Award. His story “The Cambist and Lord Iron: A Fairy Tale of Economics” was nominated for the Hugo, World Fantasy, and Seiun Awards. Abraham has two additional Hugo nominations in collaboration with Ty Franck using the pseudonym James S.A. Corey for their novel Leviathan Wakes and for ther series The Expanse, which has been turned into a successful television series. Abraham has also published using the names M.L.N. Hanover and Daniel Hanover. In addition to his collaborations with Franck, he has collaborated with Gardner Dozois and George R.R. Martin, Susan Fry, Michaela Roessner, Sage Walker, and Walter Jon Williams.

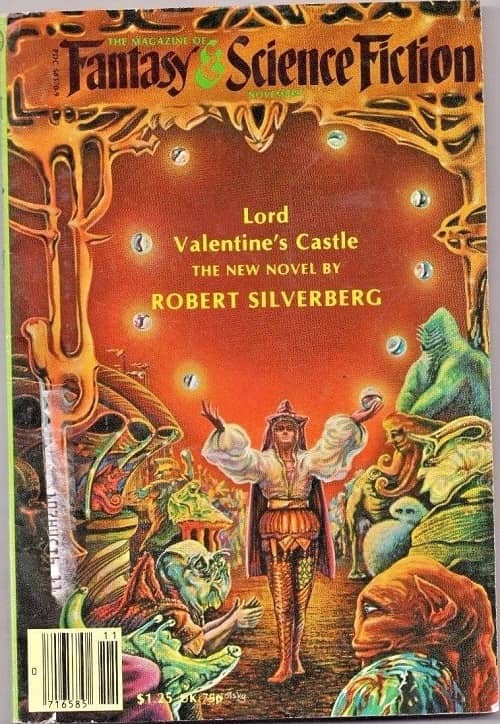

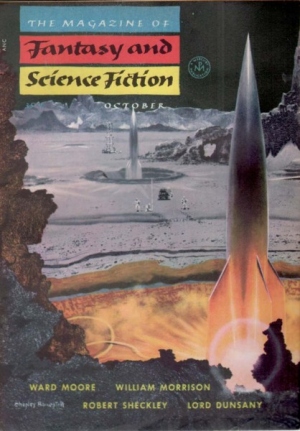

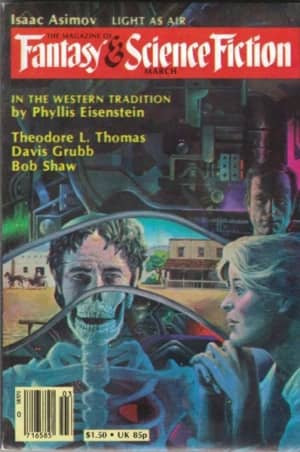

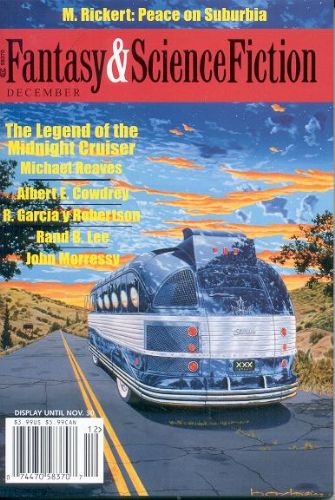

“Pagliacci’s Divorce” was published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, edited by Gordon van Gelder in its December 2003 issue. The story has never been reprinted.

Although “Pagliacci’s Divorce” is built around a sting operation based on Pagliacci’s ability to help create fake phenotype cards of illicit purposes, it really focuses on the relationship between Pagliacci and his ex-wife, Carly, whose current husband, Damon Weiss, is the target of the sting. Law enforcement uses people like Pagliacci as informants in return for letting them continue to run their scams and in this case has found a connection to a larger fish.

Abraham builds a complex relationship between Pagliacci and Carly, which points out that a divorce, even when children are not involved, does not necessarily sever the couple or their relationship. Yes, Carly has married a new man, but she and Pagliacci still have a relationship that can be leveraged, even if she is unaware of the way she is being used. However, even as Pagliacci realizes that he has to permit law enforcement to use him to get to Carly’s husband, he also knows that there are ways he can subvert the process because of his own attachment to her, the same attachment they are so adamant to use.