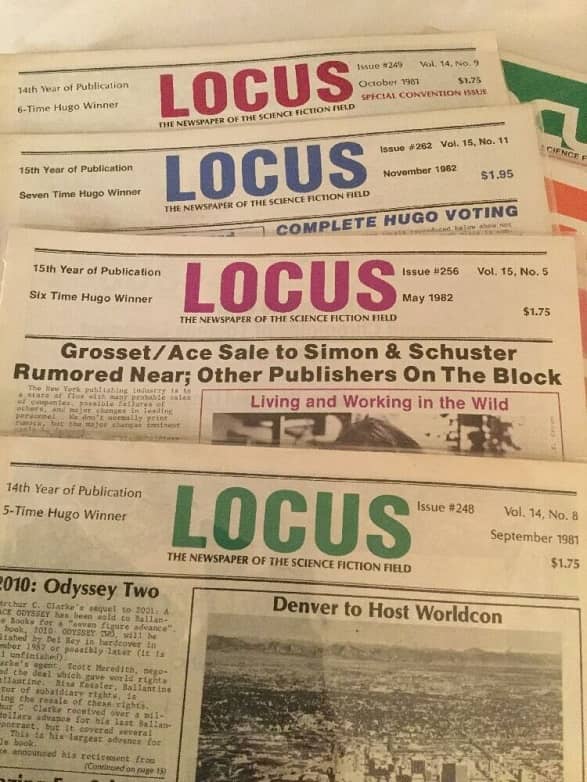

The Golden Age of Science Fiction: The 1973 Locus Award for Best Fanzine: Locus

Steven Silver has been doing a series covering the award winners from his age 12 year, and Steven has credited me for (indirectly) suggesting this, when I quoted Peter Graham’s statement “The Golden Age of Science Fiction” is 12, in the “comment section” to the entry on 1973 in Jo Walton’s wonderful book An Informal History of the Hugos. You see, I was 12 in 1972, so the awards for 1973 were the awards for my personal Golden Age. And Steven suggested that much as he is covering awards for 1980, I might cover awards for 1973 here in Black Gate.

In discussing this award I must begin with the obvious disclaimer – I write a regular column for Locus, and have done so since 2002. As such I am, I freely acknowledge, prejudiced in favor of the magazine. And I remember the thrill it was, sitting in the audience at the Hugo ceremonies, to hear my name mentioned by Liza Groen Trombi, the current editor, when she accepted our final Hugo for Best Semiprozine in Chicago in 2012 (coincidentally the final Hugo that Locus would receive, as rules changes made us ineligible in that category.) (Side personal note – I was sitting with Alec Nevala-Lee at that award ceremony – and Alec this year is nominated for a Hugo for Best Related Book for his exceptional biography Astounding.)