Call for Backers! DreamForge Magazine Publishes Standout Stories Like John Jos. Miller’s Ghost of a Smile

DreamForge started with a bang last year, publishing fifty short stories, twelve of which made Tangent Online’s Recommended Reading List. Now they’re planning year two, and need your support on Kickstarter!

One of my favorite stories from last year was “Ghost of a Smile” by John Jos. Miller, with this gorgeous illustration by Elizabeth Leggett. John was kind enough to answer a few questions. Those of you who are unfamiliar with John may, in fact, have read his books. He’s worked in genre fiction for decades, writing everything from media tie-in to Wild Cards, the shared world series edited by George RR Martin and Melinda Snodgrass. Read on to learn more about his work.

One of my favorite stories from last year was “Ghost of a Smile” by John Jos. Miller, with this gorgeous illustration by Elizabeth Leggett. John was kind enough to answer a few questions. Those of you who are unfamiliar with John may, in fact, have read his books. He’s worked in genre fiction for decades, writing everything from media tie-in to Wild Cards, the shared world series edited by George RR Martin and Melinda Snodgrass. Read on to learn more about his work.

Emily Mah: You’ve been in the business a long time and written a lot of excellent books, from media tie-in to the Wild Cards shared universe. Can you give a rough overview of your work to date?

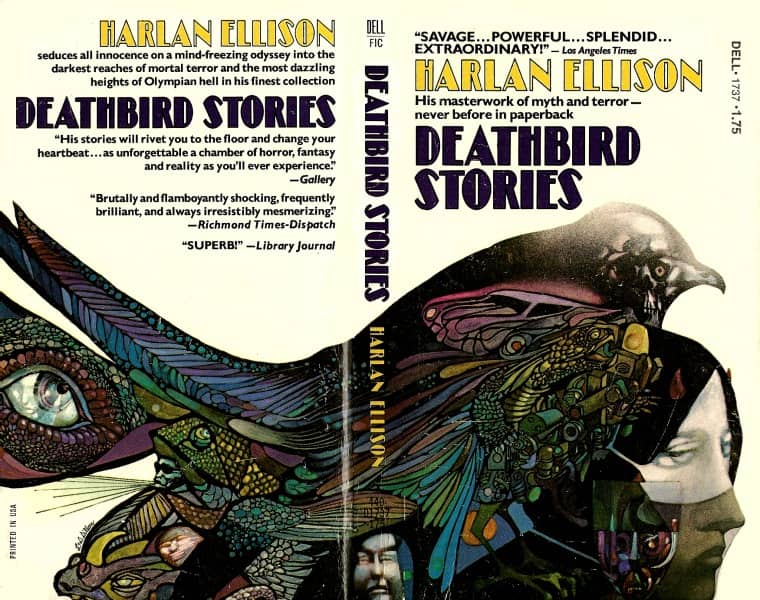

John Jos. Miller: Yeah, it’s been awhile. Somewhat longer than I’d like to admit, though I did get an early start. I don’t remember exactly when I started writing stories, but I was collecting my first rejection slips when I was about fourteen. I made my first sale to a pro publication when I was sixteen (anyone else remember Witchcraft and Sorcery, which started out as Coven-13?), but the magazine folded before it could print the story, or more importantly, pay me for it. That started an unfortunate trend that lasted for three or four other stories, but finally I sold to one that lasted long enough to both print the story and pay me (it was, in fact, the last story of the last issue of the original run of Fantastic Stories, so perhaps I deserve at least partial blame for killing that one). I had actually written and sold three novellas to Space & Time in the interim, but given the vicissitudes of small press publishing, those didn’t appear until after the story in Fantastic, and Space & Time was such a good ‘zine that even I couldn’t kill it – in fact, it’s still being published today.