Hope Among the Ruins

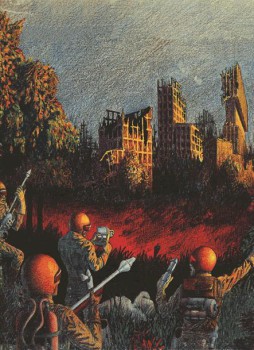

As I creep closer to the half-century mark, I find myself reflecting ever more often on my childhood. Though born at the tail end of the 1960s, I consider myself a child of the ’70s, since it was the images and obsessions of that decade that left the strongest impressions on my young imagination. I’ve mentioned before that popular culture in the 1970s was awash with the weird, the occult, and the apocalyptic. The latter saw its expression in the flowering of the “disaster movie” genre, which attained a kind of Golden Age in those days. Nowadays, the disaster films people most recall are fairly conventional ones, like Airport (1970), The Poseidon Adventure (1972), and The Towering Inferno (1974) – all of which I watched on network television after their theatrical releases – but the ones that had the greatest impact on me were those with a more global scope, like The Andromeda Strain (1971), The Omega Man (1971), and Meteor (1979). These were the motion pictures that fed my lifelong fascination with The End of the World as We Know It.

As I creep closer to the half-century mark, I find myself reflecting ever more often on my childhood. Though born at the tail end of the 1960s, I consider myself a child of the ’70s, since it was the images and obsessions of that decade that left the strongest impressions on my young imagination. I’ve mentioned before that popular culture in the 1970s was awash with the weird, the occult, and the apocalyptic. The latter saw its expression in the flowering of the “disaster movie” genre, which attained a kind of Golden Age in those days. Nowadays, the disaster films people most recall are fairly conventional ones, like Airport (1970), The Poseidon Adventure (1972), and The Towering Inferno (1974) – all of which I watched on network television after their theatrical releases – but the ones that had the greatest impact on me were those with a more global scope, like The Andromeda Strain (1971), The Omega Man (1971), and Meteor (1979). These were the motion pictures that fed my lifelong fascination with The End of the World as We Know It.

Growing up, I was possessed of the sense that life wasn’t necessarily as stable or as safe as it seemed to be on the surface. Real world events during the 1970s only made this point more forcefully. From the Energy Crisis to stagflation and fears of overpopulation and social unrest, life appeared awfully precarious in those days. And, of course, the ups and downs of relations between “the Free World” and the Soviet Bloc did little to suggest otherwise. Being a child, even a precocious one, I didn’t completely understand the full implications of a global thermonuclear war. I only knew that World War III (as my friends and I conceived it back then) was a virtual certainty, a belief reinforced by all manner of adults, from political commentators who publicly fretted about the implications of Ronald Reagan’s possible election in 1980 to my childhood idol, Carl Sagan, who regularly voiced his opinion that mankind was far more likely to destroy itself than to travel to other worlds.

Despite this, I can’t say that I was frightened by the prospects of the world’s end. Sure, I didn’t look forward to it, but I was just a kid and and I knew that, regardless of my feelings, there was nothing I could do to stave off Armageddon, so why worry? I’d read enough history by this point to realize that no world truly ends. Wars, plagues, and other sundry catastrophes were frequently devastating, marking the end of one era, but something almost always came afterwards. At my young age, I found it hard to countenance the possibility that even a nuclear war would spell the end of everything (despite that being the very reason why so many people lived in utter terror of it). I’d also read enough fantasy and science fiction to conclude that the End of the World might be adventuresome.

As might be expected from the guy who wrote

As might be expected from the guy who wrote  Now space opera and western are not terribly dissimilar, but

Now space opera and western are not terribly dissimilar, but