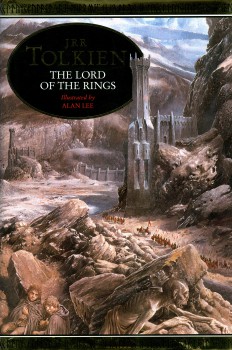

Is The Lord of the Rings Literature?

Part 2 of a 2-part series

Part 2 of a 2-part series

Part 1 of this article set the stage for the question, Is The Lord of the Rings literature? Part II examines six criteria commonly used to define works of high literary quality and applies them to The Lord of the Rings.

1. Popular appeal

The argument against: The Lord of the Rings might be popular, but that doesn’t make it literature.

The counterargument: There’s popular, and then there’s an omnipresent, mammoth, overshadowing level of popularity.

How popular is The Lord of the Rings? At last count, it has been translated into 57 languages and is the second best-selling novel ever written, with over 150 million copies sold. Its also a repeat winner of multiple international contests for favorite novel (note the broad term novel, not just fantasy novel). For example:

- In 1997 it topped a Waterstone’s poll for Top 100 Books of the Century.

- In 2003 a survey (The Big Read) was conducted in the United Kingdom to determine the nation’s best-loved novel of all time. More than three quarters of a million votes were received, and the winner was The Lord of the Rings.

- A 1999 Amazon poll administered to its customers yielded the same result.

In short, readers of all stripes, from all around the world, adore this book more than just about any other.

All that said, I will fully admit that this is the least convincing argument, because mass appeal is not necessarily a good indicator of quality. See Justin Bieber. So let’s look at some other criteria.

By way of beginning a discussion about Romanticism and fantasy, I’d like to take a quick look at where the Romantics came from. If Romanticism was a revolt against Reason, what was Reason understood to be? If Romanticism, as I feel, is essentially fantastic, is Reason opposed to fantasy? To know Romanticism is to know the Enlightenment which it was reacting against, so in this post I’ll try to describe some characteristics of the 18th-century Enlightenment in England that seem relevant to the development of fantasy. I’ll go up to about 1760, and then in my next post point out some of the counter-currents and proto-Romantic elements that were developing at the time and after.

By way of beginning a discussion about Romanticism and fantasy, I’d like to take a quick look at where the Romantics came from. If Romanticism was a revolt against Reason, what was Reason understood to be? If Romanticism, as I feel, is essentially fantastic, is Reason opposed to fantasy? To know Romanticism is to know the Enlightenment which it was reacting against, so in this post I’ll try to describe some characteristics of the 18th-century Enlightenment in England that seem relevant to the development of fantasy. I’ll go up to about 1760, and then in my next post point out some of the counter-currents and proto-Romantic elements that were developing at the time and after.  I was planning to start the series of posts on Romanticism and fantasy this week, but something came up in the last few days that I’d like to write about; particularly since it seems to resonate with

I was planning to start the series of posts on Romanticism and fantasy this week, but something came up in the last few days that I’d like to write about; particularly since it seems to resonate with  Part 1 of a 2-part series

Part 1 of a 2-part series Before continuing the series of posts on Romanticism that I talked about last week, I’d like to write about a couple of subjects I’ve had on my mind for a while. First up is Q.D. Leavis, and her book Fiction and the Reading Public.

Before continuing the series of posts on Romanticism that I talked about last week, I’d like to write about a couple of subjects I’ve had on my mind for a while. First up is Q.D. Leavis, and her book Fiction and the Reading Public. William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki outlived his creator with a tenacity that Hodgson, a bantam rooster of a man, would have appreciated. Thomas Carnacki, resident of 472 Cheyne Walk, London, first appeared in a series of five stories (“Gateway of the Monster”, “The House Among the Laurels”, “The Whistling Room”, “The Horse of the Invisible”, and “The Searcher of the End House”) in The Idler Magazine in the January through April, as well as June, issues of 1910. But despite Hodgson’s death in World War I, Carnacki carried on in a further four stories (“The Thing Invisible”, “The Hog”, “The Haunted Jarvee” and “The Find”) retrieved from Hodgson’s papers by his wife.

William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki outlived his creator with a tenacity that Hodgson, a bantam rooster of a man, would have appreciated. Thomas Carnacki, resident of 472 Cheyne Walk, London, first appeared in a series of five stories (“Gateway of the Monster”, “The House Among the Laurels”, “The Whistling Room”, “The Horse of the Invisible”, and “The Searcher of the End House”) in The Idler Magazine in the January through April, as well as June, issues of 1910. But despite Hodgson’s death in World War I, Carnacki carried on in a further four stories (“The Thing Invisible”, “The Hog”, “The Haunted Jarvee” and “The Find”) retrieved from Hodgson’s papers by his wife.  I’ve been thinking over the past few days about last week’s post on

I’ve been thinking over the past few days about last week’s post on  Perhaps my favourite fantasy writing is arguably not fantasy at all. The epics and prophecies of William Blake certainly read like fantasy to many people, I think, albeit fantasy in a distinctive, unfamiliar form. But is the word appropriate? Blake himself was a visionary — he literally saw visions — and may well have believed that some at least of his writing was literally true. Does the definition of fantasy reside in the writer, or the reader? And how would Blake himself want his writing to be viewed?

Perhaps my favourite fantasy writing is arguably not fantasy at all. The epics and prophecies of William Blake certainly read like fantasy to many people, I think, albeit fantasy in a distinctive, unfamiliar form. But is the word appropriate? Blake himself was a visionary — he literally saw visions — and may well have believed that some at least of his writing was literally true. Does the definition of fantasy reside in the writer, or the reader? And how would Blake himself want his writing to be viewed? Fantasy fiction is very often set either in the European Middle Ages, or in lands that are intentionally highly reminiscent of the Middle Ages in terms of technology and social structure. It is true that the use of European medieval settings is less common now than it has been, and also true that there have always been counter-examples. But it seems that much fantasy still relies on the European Middle Ages to define itself, one way or another. Sadly, one often has a sense that these backgrounds are not wholly thought-through; not realised as completely as they might be. The setting in a lot of fantasy, particularly I think in commercial fantasy fiction, seems to be a very generic Middle Ages in which medieval stereotypes mix with unexamined modern assumptions.

Fantasy fiction is very often set either in the European Middle Ages, or in lands that are intentionally highly reminiscent of the Middle Ages in terms of technology and social structure. It is true that the use of European medieval settings is less common now than it has been, and also true that there have always been counter-examples. But it seems that much fantasy still relies on the European Middle Ages to define itself, one way or another. Sadly, one often has a sense that these backgrounds are not wholly thought-through; not realised as completely as they might be. The setting in a lot of fantasy, particularly I think in commercial fantasy fiction, seems to be a very generic Middle Ages in which medieval stereotypes mix with unexamined modern assumptions. If I’m counting right, this marks my fifty-second post on Black Gate, which means this is effectively an anniversary. At any rate, it’s a good point to pause and reflect, I think. Writing here’s been a blast, from my first piece about Howden Smith’s collection of historical adventures Grey Maiden, up through last week’s essay on the origin story of Steve Ditko’s Doctor Strange. I’m eager to keep going, too; I feel like I’ve gotten better as a writer and critic from posting on this site, and I feel like I’ve begun to understand certain things about the nature of fantasy. I have to thank John O’Neill for inviting me to join his team, and Claire Cooney for her editing work; both John and Claire are accessible and generous with their time, and make posting here easy and fun. I also want to thank all the other bloggers who make this site, I feel, one of the best places on the web for fantasy fans. And especially I want to thank everyone who’s read and commented on my posts over the past year; I’ve been impressed with the level of responses I’ve seen, on my posts and others’, and fascinated by the conversations that’ve developed.

If I’m counting right, this marks my fifty-second post on Black Gate, which means this is effectively an anniversary. At any rate, it’s a good point to pause and reflect, I think. Writing here’s been a blast, from my first piece about Howden Smith’s collection of historical adventures Grey Maiden, up through last week’s essay on the origin story of Steve Ditko’s Doctor Strange. I’m eager to keep going, too; I feel like I’ve gotten better as a writer and critic from posting on this site, and I feel like I’ve begun to understand certain things about the nature of fantasy. I have to thank John O’Neill for inviting me to join his team, and Claire Cooney for her editing work; both John and Claire are accessible and generous with their time, and make posting here easy and fun. I also want to thank all the other bloggers who make this site, I feel, one of the best places on the web for fantasy fans. And especially I want to thank everyone who’s read and commented on my posts over the past year; I’ve been impressed with the level of responses I’ve seen, on my posts and others’, and fascinated by the conversations that’ve developed.