The Nightmare Men: The Good Inspector

Like Van Helsing before him, Inspector John Raymond Legrasse has only had one canonical appearance: HP Lovecraft’s seminal “The Call of Cthulhu”. But like the Dutch professor, the Creole Inspector has continued on past the end of his own story, popping up here and there, stubbornly inserting himself into the arcane worlds of others, most notably those of CJ Henderson.

Like Van Helsing before him, Inspector John Raymond Legrasse has only had one canonical appearance: HP Lovecraft’s seminal “The Call of Cthulhu”. But like the Dutch professor, the Creole Inspector has continued on past the end of his own story, popping up here and there, stubbornly inserting himself into the arcane worlds of others, most notably those of CJ Henderson.

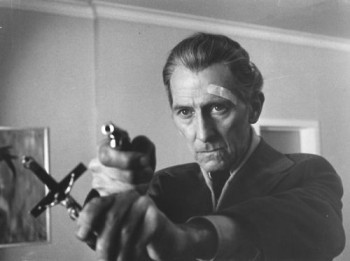

Described as a “commonplace looking middle-aged man”, Legrasse is a man devoted to duty and possessed of an unshakeable resolve, despite his unassuming appearance. This resolve pitches him into conflict with the servants of one of Lovecraft’s most enduring creations, Cthulhu. Legrasse’ part in “The Call of Cthulhu” is a minor one, but its reverberations reach far, especially when one considers how much a template ‘The Tale of Inspector Legrasse’ is for the modern occult detective story.

Abraham Van Helsing only had one truly canonical appearance, arriving as he did mid-way through Bram Stoker’s Dracula. However, so strong was the Dutch professor’s hold on the public imagination, and so fierce his rivalry with the Lord of the Undead, that he has followed his nightmare enemy into the Twentieth Century like a gin-drinking Fury.

Abraham Van Helsing only had one truly canonical appearance, arriving as he did mid-way through Bram Stoker’s Dracula. However, so strong was the Dutch professor’s hold on the public imagination, and so fierce his rivalry with the Lord of the Undead, that he has followed his nightmare enemy into the Twentieth Century like a gin-drinking Fury. Disclaimer: This article will reference some scenes from The Avengers film. While I’ve tried to avoid specific spoilers about major twists, there are some things that give away plot elements and twists from the other Marvel Comics movies, such as Thor.

Disclaimer: This article will reference some scenes from The Avengers film. While I’ve tried to avoid specific spoilers about major twists, there are some things that give away plot elements and twists from the other Marvel Comics movies, such as Thor. Literary traditions are useful things. They’re constructions of literary critics, sure, but useful constructions. A well-articulated tradition can show how different writers deal with the same idea or theme, demonstrating different approaches to a given problem or artistic ideal. It can show affinities between writers, sometimes bringing out resemblences between different figures in such a way as to cast new light on everyone involved. At the grandest level, the whole history of writing in a given language or from a given nation can be seen to be part of a tradition, showing the evolution of a language or the concerns of a people.

Literary traditions are useful things. They’re constructions of literary critics, sure, but useful constructions. A well-articulated tradition can show how different writers deal with the same idea or theme, demonstrating different approaches to a given problem or artistic ideal. It can show affinities between writers, sometimes bringing out resemblences between different figures in such a way as to cast new light on everyone involved. At the grandest level, the whole history of writing in a given language or from a given nation can be seen to be part of a tradition, showing the evolution of a language or the concerns of a people. What follows may well be total coincidence.

What follows may well be total coincidence.

While

While  Whenever discussions of fantasy fiction arise, the question of “which came first?” inevitably follows. Newbies mistakenly think that J.R.R. Tolkien started the genre, overlooking authors like William Morris and E.R. Eddison who had already begun a rich tradition of secondary world fantasy. The same arguments swirl over the many sub-genres of fantasy, too. For example, most believe that Robert E. Howard is the proper father of swords and sorcery, beginning with his 1929 short story “The Shadow Kingdom.” But others have pled the case for Lord Dunsany’s “The Fortress Unvanquishable, Save for Sacnoth” (1908), and so on.

Whenever discussions of fantasy fiction arise, the question of “which came first?” inevitably follows. Newbies mistakenly think that J.R.R. Tolkien started the genre, overlooking authors like William Morris and E.R. Eddison who had already begun a rich tradition of secondary world fantasy. The same arguments swirl over the many sub-genres of fantasy, too. For example, most believe that Robert E. Howard is the proper father of swords and sorcery, beginning with his 1929 short story “The Shadow Kingdom.” But others have pled the case for Lord Dunsany’s “The Fortress Unvanquishable, Save for Sacnoth” (1908), and so on. Last Friday was Friday the thirteenth. It was also Clark Ashton Smith’s birthday. In memory of that conjunction, I’d like to write a bit about Smith and his work. I have only a few thoughts about Smith’s prose style; Ryan Harvey’s excellent and insightful look at Smith’s fiction can be found in four parts,

Last Friday was Friday the thirteenth. It was also Clark Ashton Smith’s birthday. In memory of that conjunction, I’d like to write a bit about Smith and his work. I have only a few thoughts about Smith’s prose style; Ryan Harvey’s excellent and insightful look at Smith’s fiction can be found in four parts,