The King of Asgard: Jack Kirby’s Thor

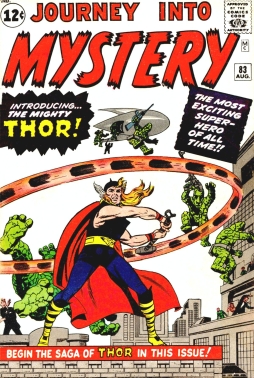

Journey Into Mystery first appeared in 1952, one of a number of anthology titles from publisher Martin Goodman’s line of comic books. Over the years, the title featured a lot of short horror, fantasy, and science fiction tales, many of them collaborations between editor/scripter Stan Lee and artists like Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby. Until 1962. At that point Goodman’s comics were beginning to change direction, following a revival of interest in the super-hero genre. A team book, The Fantastic Four, had taken off. A solo book had followed, The Incredible Hulk. Heroes would now be his company’s main product, and the line would soon come to be known as Marvel Comics. The horror anthology books would be taken over by recurring super-hero characters, and Journey Into Mystery would be the first of the bunch. So with issue 83, in August 1962, in a story credited to Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby, it introduced its new lead: the mighty Thor, Norse god of thunder.

Journey Into Mystery first appeared in 1952, one of a number of anthology titles from publisher Martin Goodman’s line of comic books. Over the years, the title featured a lot of short horror, fantasy, and science fiction tales, many of them collaborations between editor/scripter Stan Lee and artists like Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby. Until 1962. At that point Goodman’s comics were beginning to change direction, following a revival of interest in the super-hero genre. A team book, The Fantastic Four, had taken off. A solo book had followed, The Incredible Hulk. Heroes would now be his company’s main product, and the line would soon come to be known as Marvel Comics. The horror anthology books would be taken over by recurring super-hero characters, and Journey Into Mystery would be the first of the bunch. So with issue 83, in August 1962, in a story credited to Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby, it introduced its new lead: the mighty Thor, Norse god of thunder.

Donald Blake, a physician with a leg injury, takes a vacation in Norway. There, he stumbles across an invasion of the planet Earth by Stone Men from Saturn. Fleeing the aliens, and losing his cane in the process, Blake stumbles into a cave, where he finds a gnarled walking-stick lying on an altar-like stone. In frustration, he slams the stick into the cave wall and is transformed into Thor, vastly strong and able to summon storms at will. He defeats the Stone Men and embarks on an increasingly fascinating series of adventures.

Kirby drew the book sporadically between issues 83 and 100, then consistently from 101 through to the point where he left Marvel — number 179, with a fill-in by Buscema on the issue before. While, as I’ve said before, it’s difficult to make definitive statements about who did what creatively in the early Marvel comics, it’s safe to say that Kirby was the primary creative force here as with most of his other books. The Marvel method meant that he was structuring and probably plotting stories, as well as suggesting dialogue beats. I think Thor represented one of his great accomplishments, a working-out of some of his major themes; evolution, myth, life, and death. It’s not only an anticipation of his later New Gods series, but a powerful work of children’s literature in its own right — and, like much of the best children’s literature, it can be read for pleasure by receptive adults as well.

One of the oddest, most esoteric regrets in my life is that I long ago gave away my collection of the now defunct American Film magazine. Most of these, purchased primarily from sidewalk vendors in Manhattan, I do not care to recover; but I would give a great deal to have again the October issue from 1986. It contains a dialogue with film producer David Puttnam, and one small paragraph in that interview taught me more about collaboration than any other single event I know.

One of the oddest, most esoteric regrets in my life is that I long ago gave away my collection of the now defunct American Film magazine. Most of these, purchased primarily from sidewalk vendors in Manhattan, I do not care to recover; but I would give a great deal to have again the October issue from 1986. It contains a dialogue with film producer David Puttnam, and one small paragraph in that interview taught me more about collaboration than any other single event I know.

I’ve been thinking a fair bit lately about how I read what I read, and how I enjoy it. Or, what’s in it that I enjoy. It seems to me that much of the pleasure in my reading comes about from bad habits. Which is to say, habits that I can’t help but think ought to be bad, but which nevertheless feel central to the act of reading. Maybe that feeling’s an illusion; maybe it’s the secret why bad habits become habits. At any rate, I thought I’d be self-indulgent this week and throw out what I’ve come up with, as I’d love to hear if any of it resonates with anyone else’s experience of reading.

I’ve been thinking a fair bit lately about how I read what I read, and how I enjoy it. Or, what’s in it that I enjoy. It seems to me that much of the pleasure in my reading comes about from bad habits. Which is to say, habits that I can’t help but think ought to be bad, but which nevertheless feel central to the act of reading. Maybe that feeling’s an illusion; maybe it’s the secret why bad habits become habits. At any rate, I thought I’d be self-indulgent this week and throw out what I’ve come up with, as I’d love to hear if any of it resonates with anyone else’s experience of reading. Today, with finally a free minute between holiday commitments and work deadlines, I took a minute to hop over to Patrick Rothfuss’s blog, because I had not yet donated to the Worldbuilders charity and, as you can see on the right, Rothfuss and I (and my wife) are all pretty tight … and contemplative.

Today, with finally a free minute between holiday commitments and work deadlines, I took a minute to hop over to Patrick Rothfuss’s blog, because I had not yet donated to the Worldbuilders charity and, as you can see on the right, Rothfuss and I (and my wife) are all pretty tight … and contemplative. Just as an older generation recalls with perfect clarity where they were when they heard of Kennedy’s assassination, I know precisely where I first saw Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975): perched on the floral-print sofa in my parent’s house, watching the film on a poor, weather-impacted PBS broadcast. I also remember falling right off that sub-par couch in paroxysms of laughter when the animator saved King Arthur’s band by conveniently suffering a heart attack.

Just as an older generation recalls with perfect clarity where they were when they heard of Kennedy’s assassination, I know precisely where I first saw Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975): perched on the floral-print sofa in my parent’s house, watching the film on a poor, weather-impacted PBS broadcast. I also remember falling right off that sub-par couch in paroxysms of laughter when the animator saved King Arthur’s band by conveniently suffering a heart attack.

Once upon a very suspect time, a human being by the name of Terry Pratchett conjured up a space-traveling sea turtle by the name of A’tuin, and proceeded to make a sizable fortune from the disc-shaped world he emplaced upon her. In Pratchett’s Discworld novels, magic of the most unpredictable kind is the norm, and so it should come as no surprise that, eventually, somebody had to commit his unique brand of literary lunacy to celluloid.

Once upon a very suspect time, a human being by the name of Terry Pratchett conjured up a space-traveling sea turtle by the name of A’tuin, and proceeded to make a sizable fortune from the disc-shaped world he emplaced upon her. In Pratchett’s Discworld novels, magic of the most unpredictable kind is the norm, and so it should come as no surprise that, eventually, somebody had to commit his unique brand of literary lunacy to celluloid. ‘His eyes were icy verdigris, but warm also, and piercing — in a kind way. He was dressed smartly in a long coat of an almost military cut and dark pants with gold piping.’ So writes the narrator of the 2012 story, “The Portobello Cetacean” as she first lays eyes on her host, Sgt. Roman Janus, late of Mount Airy, the man known as the ‘spirit-breaker’.

‘His eyes were icy verdigris, but warm also, and piercing — in a kind way. He was dressed smartly in a long coat of an almost military cut and dark pants with gold piping.’ So writes the narrator of the 2012 story, “The Portobello Cetacean” as she first lays eyes on her host, Sgt. Roman Janus, late of Mount Airy, the man known as the ‘spirit-breaker’.