“What have I been reading lately, you ask?” Oh. You didn’t say that. Well, I’m going to tell you anyways. When I ‘get into’ something, I jump in full-bore for a short time: up way past my elbows. That’s how most of my series’ here at Black Gate start. Fortunately, I can be reading a couple different books simultaneously, and I also listen to audiobooks to help cover more ground (though I ALWAYS prefer reading to listening).

“What have I been reading lately, you ask?” Oh. You didn’t say that. Well, I’m going to tell you anyways. When I ‘get into’ something, I jump in full-bore for a short time: up way past my elbows. That’s how most of my series’ here at Black Gate start. Fortunately, I can be reading a couple different books simultaneously, and I also listen to audiobooks to help cover more ground (though I ALWAYS prefer reading to listening).

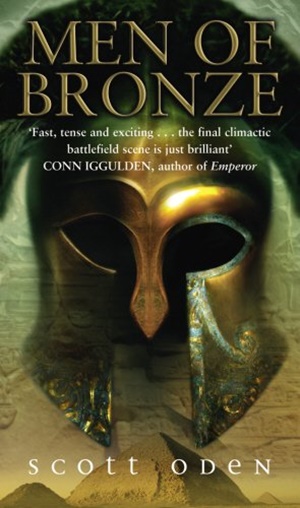

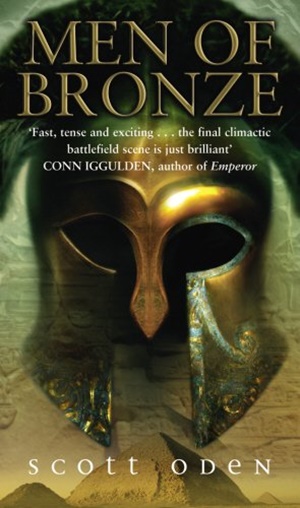

SCOTT ODEN

And I recently went on a short Sword and Sandals kick. Scott Oden and I have become friends through our mutual love of Robert E. Howard: he did the “Devil in Iron” entry for Hither Came Conan. I grabbed the digital version of Men of Bronze (a STEAL at $3.99!). It’s historical fiction (non-fantasy) set in 529 BC in ancient Egypt. It’s near the end of the time of the Pharaohs and Egypt is trying to hold off the encroaching Persian Empire. As is often the case with faltering empires, it is relying heavily on mercenaries to keep order.

Hasdrabal Barca is the protagonist; the deadliest mercenary of them all, leading the fight to stop the betrayal of Greek mercenaries, and the ambitious Persians. I had trouble keeping the various names straight, but I very much liked this book. It’s got a grand sweep, and I love Scott’s depiction of Egypt. There’s a rough scene early on, but fortunately, that not the norm for the rest of the book. Much recommended. I also bought his Greek historical novel, Memnon, at the same time (same price). It’s on my massive To Read list.

HOWARD ANDREW JONES

Of course, I couldn’t just read one book of a type, and move on. That’s not me! Howard Andrew Jones was Black Gate’s first Managing Editor (a post recently assumed by Seth Lindberg) and is currently receiving rave reviews for his epic fantasy, The Ring-Sworn Trilogy. I had not yet read his two fantasy Sword and Sorcery novels, featuring the wise and learned scholar Dabir and the brave man of action, Asim (I was not totally unfamiliar with them – more on that below).

So, I got the audiobook for Desert of Souls, the first novel. The adventures take place in a fantasy-real version of Arabia, with sorcery and monsters. And there’s a Robert E. Howard Easter Egg near the end. I like the main characters, and their world, so I have started on the audio book of Bones of the Old Ones.

I had already read The Waters of Eternity; a collection of six short stories featuring the two men. I re-read it, and I actually prefer it to the novels. They are really mysteries, set in that fantasy Arabia. I like the mix of fantasy and detective work, and also the shorter length. You should check them out.

NORBERT DAVIS

For months, I have been listening repeatedly, to an audiobook of the five Max Latin short stories. I simply never get tired of them. The woefully under-appreciated Davis, who I wrote about last week, as well as last year, is on my Harboiled Mt. Rushmore. And the stories about the not-as-crooked-as-he-pretends Latin are the best of the bunch. I listen and read them throughout the year.

I also picked up volumes one and two of The Complete Cases of Bail Bond Dodd, the first series character that Davis created for Dime Detective Magazine. The Dodd and Latin collections are from Steeger Books. You should be reading some Davis.

…

Read More Read More