Adventure On the Page: Genre Fiction vs. Joyce Carol Oates

The more I write, the more opprobrium I feel for categorical definitions of fiction, notably “genre fiction” and “literary fiction.” I like to think I practice both, and that most readers read both. Crazier still –– lunacy, truly –– I suffer the apparent delusion that often the two categories cannot be separated, except by book vendors aiming to simplify or streamline the shopping experience.

The more I write, the more opprobrium I feel for categorical definitions of fiction, notably “genre fiction” and “literary fiction.” I like to think I practice both, and that most readers read both. Crazier still –– lunacy, truly –– I suffer the apparent delusion that often the two categories cannot be separated, except by book vendors aiming to simplify or streamline the shopping experience.

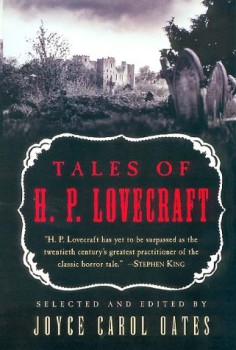

Not long ago, I delved back into Joyce Carol Oates’s introduction to a delicious anthology, Tales of H.P. Lovecraft, and I came across this passage:

However plot-ridden, fantastical or absurd, populated by whatever pseudo-characters, genre fiction is always resolved, while literary fiction makes no such promises; there is no contract between reader and writer for, in theory at least, each work of literary fiction is original, and, in essence, “about” its own language; anything can happen, or, upon occasion, nothing.

Now –– and I say this as a long-time and self-avowed fan of your work, Ms. Oates –– them’s fightin’ words.

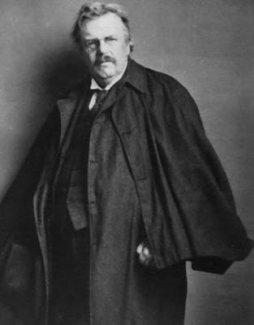

Last week, in a post about Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, I said that certain habits of Gaiman’s plotting reminded me of G.K. Chesterton. It seemed to me that I’d referred to Chesterton fairly often in my posts here, so I did a search of the Black Gate archive. I found that I had in fact mentioned Chesterton a number of times, but that neither I nor anyone else had yet written a post for Black Gate specifically about him or any of his works. I’ve therefore put together this piece to give an overview of the man and his writing. It’s insufficient; Chesterton’s difficult to describe, more so than most writers. But one has to begin somewhere. He’s an important early fantasist, admired by figures as diverse as Gaiman, Borges,

Last week, in a post about Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, I said that certain habits of Gaiman’s plotting reminded me of G.K. Chesterton. It seemed to me that I’d referred to Chesterton fairly often in my posts here, so I did a search of the Black Gate archive. I found that I had in fact mentioned Chesterton a number of times, but that neither I nor anyone else had yet written a post for Black Gate specifically about him or any of his works. I’ve therefore put together this piece to give an overview of the man and his writing. It’s insufficient; Chesterton’s difficult to describe, more so than most writers. But one has to begin somewhere. He’s an important early fantasist, admired by figures as diverse as Gaiman, Borges,