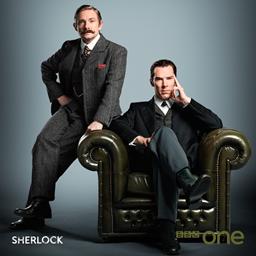

The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes: Sherlock Season 3 – What Happened?

Now, it’s certainly possible that I’m clueless (and I do LOVE Without a Clue), but I don’t think I’ve got the following all wrong regarding BBC’s Sherlock.

Now, it’s certainly possible that I’m clueless (and I do LOVE Without a Clue), but I don’t think I’ve got the following all wrong regarding BBC’s Sherlock.

Except for the grumpy old man contingent (‘Get Sherlock out of modern day!’), fans of Holmes, including scholarly geeks like me who make their own newsletter, overwhelmingly liked this new show and the three episode season one.

I don’t know too many Holmes fans (other than GOM group: see above) who disliked this show. Even those who were moderately approving seemed pleased and intrigued with it and willing to tune in for another season.

So, season two came along, and more huzzahs and approval. I don’t remember Holmes friends of mine thinking it was going south. I certainly didn’t: I thought the first two seasons were brilliant and fun updatings of the great detective. I found cool references to Doyle’s tales all over the place.

Once again, no comments that it jumped the shark. Folks were absolutely looking forward to seeing how Holmes survived his Reichenbach Fall. It was one of my five all time favorite tv shows and probably battling Justified for number one.