NaNoWriMo is coming!

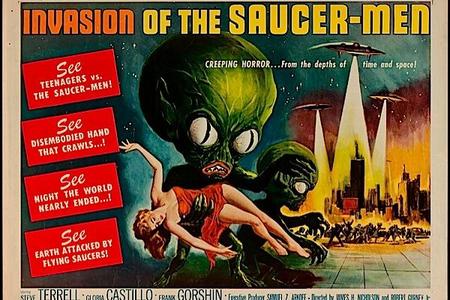

Like Winter, NaNoWriMo is coming and aspiring writers are even now planning to do a Frazetta on the whole business of writing a novel. This is great — momentum is all — but it’s way too easy to grind to a halt or lose time going round in circles trying to reinvent the wheel.

I wrote a book on all this, but some of my previous blog entries might also help you avoid dead ends and rampage through your novel to the very end — I promise you both an affirming and life changing experience.

So, here they are in digest form:

Some Writing Advice That’s Mostly Useless (And Why): The following writing advice is mostly useless — “Work on your motivation,” “Revise, revise, revise,” “Have a chaotic life,” “Just write,” “Know grammar and critical terms,” “Practice skills in isolation.”

World Building Historical Fiction using Military Thinking: Don’t fall down the rabbit hole of research or worldbuilding. Instead use a layered approach, focussing your world building as you descend from Strategic (villas exist and can be raided for supplies), through Operational (this villa sits on this ground amidst these fields), to Tactical (here is the ground plan of the villa and here are the people guarding it) level.

NaNoWriMo: How to “Pants” Through Your Novel like a Rampaging Panzer Division in 1940 France (and Why You Should): If you subscribe to the “Just Write” approach, then — seriously — just write. Switch off your spell checker, don’t edit or tinker, and if you need to add something to the story, just make a note and move on. You can mop up later.

Time flies when you’re having fun. My

Time flies when you’re having fun. My