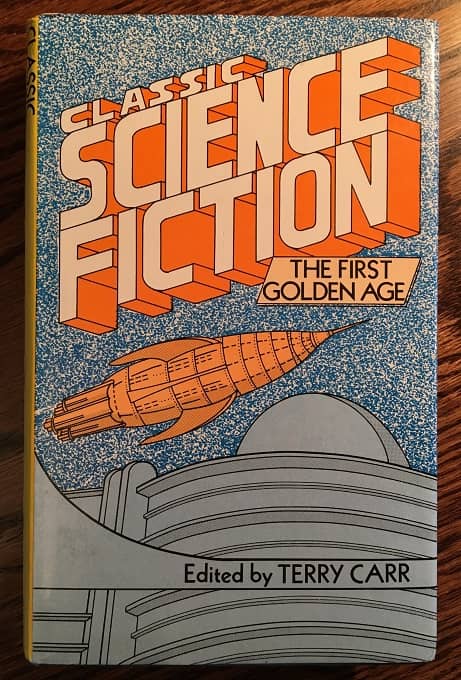

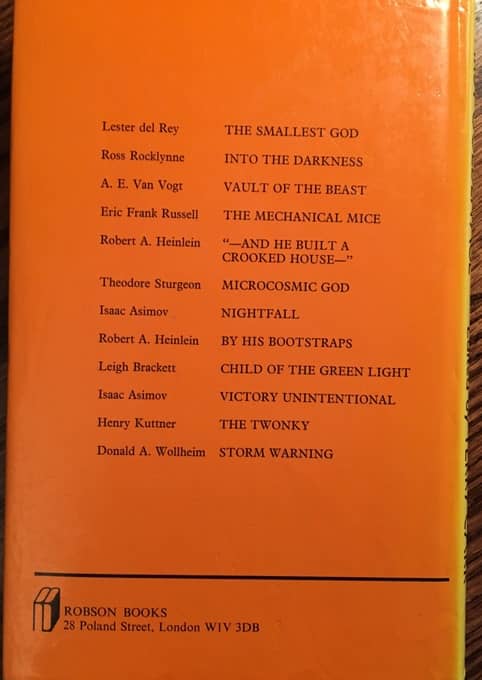

The Games Plus 2019 Spring Auction: Part One

A few of the treasures acquired at the 2019 Games Plus Spring Auction

I’ve been attending the Games Plus Auction in Mount Prospect, Illinois ever since David Kenzer first told me about it, when we worked at Motorola in the late 90s. So, twenty years, give or take. I’ve been writing about it here ever since my first report in 2012 (in the appropriately titled “Spring in Illinois brings… Auction Fever.”)

The four-day auction occurs twice a year, in Spring and Fall. Each day focuses on one of four popular themes: Thursday is collectable and tradable games like Magic: The Gathering and the Dungeons and Dragons Miniatures Game; Friday is historical wargames and family games; and Sunday is the massive miniatures auction, focused on Warhammer and like-minded pastimes. I’ve checked in on the others over the years, but my jam is the Saturday Science Fiction and RPG auction, which includes board games, minigames, and role playing rules, supplements, adventures, and magazines. It runs from 10:00 am to 5:00 pm, with no break, and this year was on March 2.

When I first started going, I was was on the hunt mostly for 70s and 80s RPG and gaming collectables, especially TSR gaming modules, microgames, Avalon Hill and Chaosium board games like Stellar Crusade and Dragon Pass, and of course ultra-rare Dwarfstar titles like Barbarian Prince. That’s changed dramatically over the decades. We live in a golden age of science fiction and fantasy board gaming, and between the many, many active publishers, countless Kickstarters and other crowdfunding campaigns, and seemingly numerous new role playing games, it’s impossible for me to keep track of all the new releases.

Those games show up in great quantity as the skilled auctioneers move rapid-fire through thousands of titles over seven hours, and often at bargain prices. Nowadays I attend the auction chiefly to discover what’s new and exciting in fantasy and science fiction board gaming, and see if I can’t pick up a few. It’s an expensive outing, to be sure, which is why I save up for months beforehand. I rarely escape will a bill less than a thousand dollars, and this year was no exception. When they totaled up the damage at the end of the Saturday auction, I’d spent $1,573 on games that filled some 15 boxes.