When is Writing Like a Magic Trick?

Simple. When giving the explanation ruins things. When what you don’t tell is as important as what you do tell. Or, at times, when it’s who you tell, not what you tell. After all, magicians’ assistants generally know a great deal more about the trick than the audience does – though there might be things even the assistants don’t know, at least not at first.

Simple. When giving the explanation ruins things. When what you don’t tell is as important as what you do tell. Or, at times, when it’s who you tell, not what you tell. After all, magicians’ assistants generally know a great deal more about the trick than the audience does – though there might be things even the assistants don’t know, at least not at first.

Most exposition deals with items and details known to the characters, which then have to be conveyed to the readers. What about things the characters don’t know, but the readers must? When we talk about exposition, and giving explanations, along with the how and the when, we also have to consider the who.

Writers are like magicians in this sense – we’ve got to keep our secrets, at least until the right moment when all (ahem) will be revealed. But here’s what makes our lives trickier than those of stage magicians: our readers are both the audience and the assistants. They’re watching the trick unfold, even while they’re participating in the unfolding.

Probably the most obvious example of this is the use of dramatic irony. You know, when the audience knows something the other characters in the play don’t know, because we’ve witnessed action or events that took place when they were off stage. Plays and movies manage this by, well, moving the other characters off stage – or by soliloquies if it’s Shakespeare (think of the beginning of Richard III, where he tells us what he’s going to do, and the other characters don’t know).

[Aside: ever notice that it’s always the bad guy who tells you his plans? That’s because it’s the bad guys who have plans. Good guys are just minding their own business until the bad guy acts up. I’m sure there’s a language in which “good guy” means “has no particular plans.”]

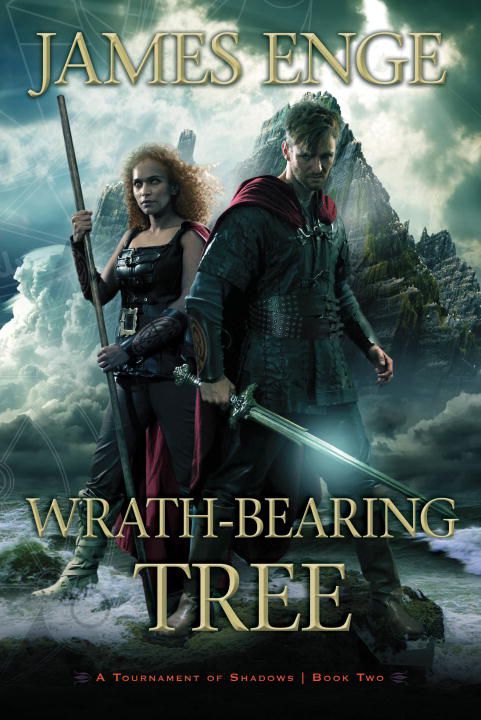

The first time I saw a James Enge novel on the shelf of my local bookstore, I broke into a little dance of jubilation. I’d been reading Enge’s short stories about Morlock the Maker in the pages of Black Gate — this was when BG had literal paper pages — and it was news to me that Enge had made the leap from short fiction to novels.

The first time I saw a James Enge novel on the shelf of my local bookstore, I broke into a little dance of jubilation. I’d been reading Enge’s short stories about Morlock the Maker in the pages of Black Gate — this was when BG had literal paper pages — and it was news to me that Enge had made the leap from short fiction to novels. Over the next few years, Enge followed Blood of Ambrose with This Crooked Way and The Wolf Age, and it turned out the one thing better than a Morlock novel was a whole trilogy of Morlock novels.

Over the next few years, Enge followed Blood of Ambrose with This Crooked Way and The Wolf Age, and it turned out the one thing better than a Morlock novel was a whole trilogy of Morlock novels.