Building a World in a Vacant Lot: The Circus of Dr. Lao

Fantasy, like all life-consuming obsessions (fly fishing, stamp collecting, running for public office) has a language all its own, one that can seem arcane and incomprehensible to the uninitiated. Polder, thinning, underlier, Dark Lord, secondary world, Hidden Monarch, threshold, time abyss, mythago – each of these names a vital fantasy concept or device, and of all such terms, none is more important to the modern genre than worldbuilding.

Fantasy, like all life-consuming obsessions (fly fishing, stamp collecting, running for public office) has a language all its own, one that can seem arcane and incomprehensible to the uninitiated. Polder, thinning, underlier, Dark Lord, secondary world, Hidden Monarch, threshold, time abyss, mythago – each of these names a vital fantasy concept or device, and of all such terms, none is more important to the modern genre than worldbuilding.

Worldbuilding is, according to Wikipedia, (the greatest repository of fantasy on the internet) the process of “developing an imaginary setting with coherent qualities such as a history, geography, and ecology,” and it “often involves the creation of maps, a backstory, and people for the world.”

In worldbuilding as in so many other things, it was J.R.R. Tolkien who set the standard for all who followed. His Middle Earth, with its immensely deep and detailed history, cosmogony, and geography, was worldbuilding on an unprecedented scale, even to the creation of complete languages for the various races that inhabit this invented milieu.

Post-Tolkien fantasy is largely the story of the primacy of this kind of worldbuilding, as the maps, glossaries, and genealogies that pad the backs of so many fat paperbacks attest, and almost all epic fantasies published since The Lord of the Rings owe a large debt to Tolkien and his example. But all writers are worldbuilders, Hemingway and Updike as much as Jordan and Martin, and perfect as the Tolkien method is for a particular kind of tale, there are many ways to create a believable world — even a fantasy one.

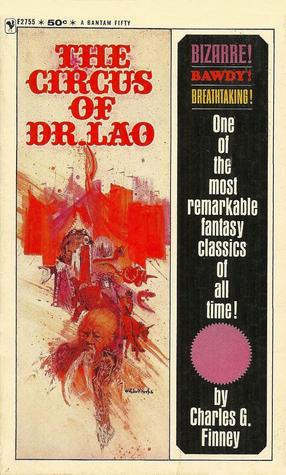

The kind of construction exemplified in The Lord of the Rings is largely external, which is well suited to Tolkien’s rather formal purposes. There is another kind of worldbuilding, however, one less concerned with royal lines and the names of rivers than with what might be called the mythic geography of ordinary life. A superb example of this kind of work is Charles G. Finney’s The Circus of Dr. Lao. Published in 1935, it is one of the greatest fantasy novels ever written; indeed, in some moods I’m inclined to think that it is the greatest of them all.

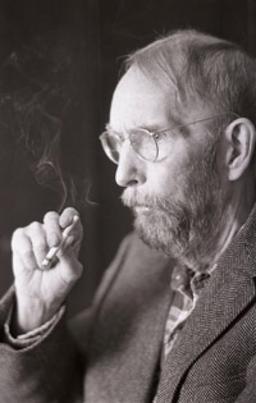

Finney spent the years 1927-30 on duty with the U.S. Army’s 15th Infantry Regiment in Tientsin, China, when international forces occupied parts of the country in the wake of the Boxer Rebellion. It was in that exotic city (probably doubly strange and colorful to a young man hailing from Sedalia, Missouri) that he conceived The Circus of Dr. Lao, his first novel, which he wrote after his discharge.

Upon returning to the United States, Finney took up residence in Tuscon, Arizona, where he worked as an editor for the Arizona Daily Star newspaper, a profession which occupied him for the rest of his working life until his retirement in 1970. During those decades he occasionally produced a bit of fiction, but his output was always light and sporadic, though The Circus of Dr. Lao attracted some critical notice when it was published, winning a National Book Award in 1935 for “Most Original Book” (a category that doesn’t exist anymore).

The award was well deserved, for if the book was original in 1935, it remains so today. (It is one thing to be original at first appearance, but to stay original for almost a century is quite another; those judges were perceptive, whoever they were.) Though unknown to the general public, the novel has never been out of print for long and has maintained a high reputation among fantasy aficionados; it was one of Ray Bradbury’s favorites and clearly influenced his own carnival novel, Something Wicked this Way Comes, and Peter S. Beagle’s The Last Unicorn is another book that follows a path that Finney first cleared.

Among the book’s many virtues, one of the most obvious is the high quality of the writing, which is remarkably unaffected and vigorous. Most of the bestsellers of 1935 have justly been pulped and forgotten, largely because, in both subject and style, they just read old. But The Circus of Dr. Lao reads as if it had been written yesterday. Few eighty year old novels have such an up to date feel, and there’s not a musty or cobwebbed sentence in it.

Among the book’s many virtues, one of the most obvious is the high quality of the writing, which is remarkably unaffected and vigorous. Most of the bestsellers of 1935 have justly been pulped and forgotten, largely because, in both subject and style, they just read old. But The Circus of Dr. Lao reads as if it had been written yesterday. Few eighty year old novels have such an up to date feel, and there’s not a musty or cobwebbed sentence in it.

If Finney doesn’t establish his originality with his unconventional story, he takes one more crack at it after the tale’s conclusion, with the Catalogue, “An explanation of the obvious that must be read to be appreciated.” This twenty page epilogue is the funniest part of an often very funny book. It’s a sort of glossary or biographical dictionary with an entry containing odd and useful — or useless — information about every single character and place and creature and deity (and even foodstuff) in the book, and Finney wraps the whole thing up by listing the “Questions and Contradictions and Obscurities”, identifying the holes in his own narrative so you won’t have to. He was nothing if not a gentleman.

Unconventional, funny, and beautifully written, The Circus of Dr. Lao is also short (about 150 pages), another bold quality that seems to have vanished as irrevocably as foreign troops in China. The book is currently in print in a nice paperback from the University of Nebraska Press, an edition that includes the wonderfully eccentric original illustrations by the Ukrainian surrealist Boris Artzybasheff. (The story was filmed in 1964 as 7 Faces of Dr. Lao, with Tony Randall playing Doctor Lao as well as several other parts. Randall is quite good, but the story was drastically changed, to its detriment.)

The Circus of Dr. Lao is a thoroughly American, egalitarian fantasy, which is not surprising, as its author was a product of that great school for egalitarian writers, the United States Army. This is a story with no princes or peasants, no knights, no warring dynasties, no history-imposed quests or burdens (if there’s one thing Americans don’t believe in, it’s history), no castles, keeps, or drawbridges, no feudal social structures. Instead, there are shopkeepers, insurance salesmen, cops, rowdy college punks, discontent housewives, sticky schoolchildren, elderly busybodies, daily newspapers, and an empty field in the city of Abalone, Arizona, a “bald spot in the city’s growth surrounded by all manner of houses and habitations.”

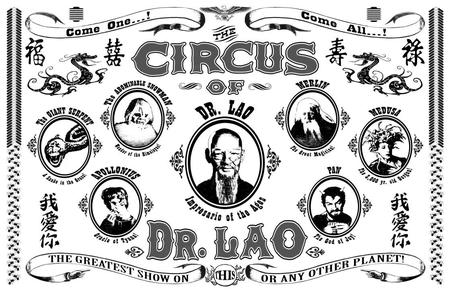

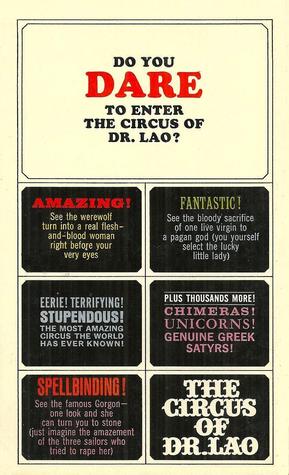

On this spot, Doctor Lao erects his circus — after placing an ad in the Abalone Morning Tribune that “made claims which even Phineas Taylor Barnum might have hedged at advancing” and after leading an enticing parade through the streets of the sleepy town to drum up business.

On this spot, Doctor Lao erects his circus — after placing an ad in the Abalone Morning Tribune that “made claims which even Phineas Taylor Barnum might have hedged at advancing” and after leading an enticing parade through the streets of the sleepy town to drum up business.

After that, the citizens of Abalone, playing hooky from school or work or household duties, arrive and spend a day at the circus. From this point on, no summary would be coherent or useful; the book is as loose and leisurely and free in form as… well, as a day at the circus. Readers and characters alike progress from the circus’s start to its finish by wandering down the midway, stopping and listening to a spiel here, poking their heads in at a tent there, pausing to chat with neighbors, and backtracking to visit a fortuneteller who is “not an ungrammatical gypsy, not a fat blonde mumbling silly things about dark men in your life, not a turbaned mystic canting of the constellations”, but is none other than Apollonius of Tyana, a two thousand year old mage doomed to tell only the truth.

Along the way we view the animals of the circus, not commonplace elephants, tigers, or monkeys, but “animals no man had ever seen before; beasts fierce beyond all dreams of ferocity, serpents cunning beyond all comprehension of guile; hybrids strange beyond all nightmares of fantasy”, and we pause to gawk at the obligatory freaks, among whom are to be found “no glass-blowers, cigarette fiends, or frogboys, but real honest-to-goodness freaks that had been born of hysterical brains rather than diseased wombs.”

Male patrons may gain admittance to a peepshow, “educational rather than pornographic,” in which, “out of the erotic dramas and dreams of long-dead times had been culled a figure here, an episode there, a fugitive vision elsewhere, all of which in combination produced an effect that no ordinary man for a long series of days would forget or, for that matter, care to remember too vividly.”

And finally, at the end of the day, the main performance takes place; visitors witness the erection of the ancient city of Woldercan and the temple of its god Yottle. At the climax, as Dr. Lao’s outrageous newspaper ad promises,

The ceremony of the living sacrifice to Yottle would be enacted: a virgin would be sanctified and slain to propitiate this deity who had endured before Bel-Marduk even, and was the first and mightiest and least forgiving of all the gods. Eleven thousand people would take part in the spectacle, all of them dressed in the garb of ancient Woldercan. Yottle himself would appear, while his worshippers sang the music of the spheres. Thunder and lightening would attend the ceremonies, and possibly a slight earthquake would be felt. All in all it was the most tremendous thing ever to be staged under canvass.

Need I say that there is not an exaggeration or a false claim in the lot? For only twenty five cents admission, it’s an undeniable bargain.

Along the way, the patrons of the circus all see extraordinary things, but not everyone sees them as extraordinary; those who are open to the miraculous are changed by their day at the circus, while those who are not leave just as obtuse and hardened as they were when they entered. One woman, Kate, literally leaves hardened, when she scoffs at Doctor Lao’s injunction not to look at the Medusa directly, but to observe only the creature’s reflection in a mirror. (Significantly, instead of being hideously ugly, the Medusa’s “beauty was startling.”) When Kate pulls back the curtain and looks directly at the mythic woman, she is instantly turned into stone. A university geologist who happens to be on the scene identifies the kind – “Never saw a prettier variegation of color in all my life. Carnelian chalcedony. Makes mighty fine building stone.” Her husband Luther has to enlist the aid of some passerby to load his former spouse onto a truck: “They never did figure out just what the hell Kate was, but they complained to Luther that the thing was awful damn heavy.”

Talking to some curious patrons about the circus’s captive mermaid, Dr. Lao (who is simply described as “an old Chinaman”) speaks of this transformative power of the beautiful and the marvelous:

We found her in the Gulf of Pei-Chihli,’ said Dr. Lao. ‘We found her there on the brown, muddy waves. They were brown and muddy because inland it had rained and the little rivers had carried the silt out into the sea. And after finding her we came upon the sea serpent, and we captured him, too. It was a most fortunate day. But she pines sometimes, I think, for her great, grey ocean. I hate to keep her penned up in this tank, but I know of nowhere else to put her. I think I shall turn her loose some day when we are showing along the seacoast. Yes, I shall take her out in the dawn when no one else is about and carry her down to the sea. Waist-deep in the water I’ll go with her in my arms, and I’ll put her down gently and let her swim away. And I shall stand there, an odd, foolish-looking old man, waist-deep in the water, mourning over the beauty I have just let slip away from me, mourning over the beauty I could touch and see but never completely comprehend; and, if anyone sees me there, waist-deep at dawn in the water, surely they will think me mad. But do you suppose that after she swims out a little ways she will turn and wave at me? Do you suppose she will blow a little kiss to me? Oh, God, if only I could have seen her as a young man! The contemplation of her beauty could have changed my whole life. Beauty can do that, can’t it?’

To this lyrical rhapsody a customer identified only as Quarantine Inspector Number One replies, “What do you feed her, Doc?” (Doctor Lao answers, “Seafoods.”) This prosaic patron has seen, but has not seen, and will return to his job unchanged, no richer for his day at the circus, only a quarter poorer.

On the other hand, in a different tent, Mr. Etaoin, an employee at the newspaper who has been lured to the circus by the outlandish claims of the ad he proofread, has a chat with the sea serpent mentioned by Doctor Lao. The creature serenely describes his life prior to his capture and his determination to one day escape with the mermaid and return to the glories of his deep ocean home. His words spark something of the same desire for beauty and freedom in the staid newspaperman, who exits the tent more alive to the possibilities of life than when he entered it.

Likewise, in yet another tent straightlaced schoolteacher Miss Agnes Birdsong finds herself alone with a satyr, and has an intimate experience which changes her forever: “The boys all said she was damned good company after she learned to smoke and drink. Dr. Lao’s circus broadened her outlook, gave her things to think about when sleepless she tossed on her couch of nights, when bored she listened to her students botch syntax of days.”

|

|

[Click for bigger images.]

After the concluding spectacle at the Temple of Yottle, a ceremony combining unexpected death and ironic blessing, some spectators are shocked and dismayed by the final sacrifice, while others show more equanimity. To the impassioned protests of the first sort, the doctor has an apt reply. In words that could be echoed by all worldbuilding writers (and that surely speak for Finney himself), he says, “The world is my idea; as such I present it to you. I have my own set of weights and measures and my own table for computing values. You are privileged to have yours.” The mundane and the miraculous are one in the same, the only arbiters being the observing eye, the receiving soul.

When all is done, “the ends of the tent fell outward and down, and the circus of Doctor Lao was over. And into the dust and the sunshine the people of Abalone went homewards or wherever else they were going.” Doctor Lao’s circus has come to town, touched those whom it could reach, and now moves on, and as always, the workaday world awaits.

The Circus of Dr. Lao doesn’t begin in a painstakingly constructed fantasy world in the manner of Tolkien; rather it begins in the heat and dust and busyness of the everyday reality that we all inhabit, and fantasy enters that reality and stakes out a patch for itself. People come and visit a vacant lot in which those who can see the magical and the numinous see it, and carry some of it away with them; those who can’t, don’t. Some have their lives profoundly altered; some just kill an afternoon. The whole tale exemplifies that very American principle, that people are entitled to what they can lay hold of for themselves — in spiritual matters as in material ones. (Finney was the grandson of one of the great Protestant preachers and theologians of the nineteenth century, whom he was named after.)

The residents of Abalone, Arizona, don’t live in a world furnished with wizards, runes, spells, and dragons; the worldbuilding that Finney does is internal rather than external. Instead of permanently infusing the entire milieu, in The Circus of Dr. Lao the magical approaches and then recedes, the immediate experience is short-lived, and transcendence afterwards persists only in memory and interpretation. In this, the novel is very close to our experience of everyday life, when the sublime may break through at any moment and we must be ready to grasp it quickly before it fades, as fade it will.

One of the great lures of literature is its promise to take us to utterly new places and give us completely new experiences, and fantasy, of all genres, makes that promise most strongly. The Circus of Dr. Lao succeeds at the high-wire act of taking us to a new place right in the heart of our common and familiar world, and giving us startling new experiences in the context of the ordinary actions of our everyday lives. In this way it makes us alert to the miraculous nature of life itself, and makes us aware that amazing things are always at our elbow, if we’ll only see them. It thereby establishes itself as that rare and genuine article, a true fantasy classic.

Out of the countless books to be read and enjoyed for a moment and then moved on from, The Circus of Dr. Lao is a book to be savored and returned to over a lifetime. It is a gift from a young man just out of the Army, first awakening to the wonders of life, and it is a book to love.

I need to reread this. Thanks for such a wonderful article on such a wondrous book.