Black Gate Online Fiction: An Excerpt from The Wall of Storms

By Ken Liu

This is an excerpt from the novel The Wall of Storms by Ken Liu, presented by Black Gate magazine. It appears with the permission of Saga Press, and may not be reproduced in whole or in part. All rights reserved. Copyright 2016 by Ken Liu.

Chapter One: Truants

PAN: the second month in the sixth year of the reign of four placid seas.

PAN: the second month in the sixth year of the reign of four placid seas.

Masters and mistresses, lend me your ears.

Let my words sketch for you scenes of faith and courage.

Dukes, generals, ministers, and maids, everyone parades

through this ethereal stage.

What is the love of a princess? What are a king’s fears?If you loosen my tongue with drink and enliven my heart

with coin, all will be revealed in due course of time…

The sky was overcast, and the cold wind whipped a few scattered snowflakes through the air. Carriages and pedestrians in thick coats and fur-lined hats hurried through the wide avenues of Pan, the Harmonious City, seeking the warmth of home.

Or the comfort of a homely pub like the Three-Legged Jug.

“Kira, isn’t it your turn to buy the drinks this time? Everyone knows your husband turns every copper over to you.”

“Look who’s talking. Your husband doesn’t get to sneeze without your permission! But I think today should be Jizan’s turn, sister. I heard a wealthy merchant from Gan tipped her five silver pieces last night!”

“Whatever for?”

“She guided the merchant to his favorite mistress’s house through a maze of back alleys and managed to elude the spies the merchant’s wife sicced on him!”

“Jizan! I had no idea you had such a lucrative skill—”

“Don’t listen to Kira’s lies! Do I look like I have five silver pieces?”

“You certainly came in here with a wide enough grin. I’d wager you had been handsomely paid for facilitating a one-night marriage—”

“Oh, shush! You make me sound like I’m the greeter at an indigo house—”

“Ha-ha! Why stop at being the greeter? I rather think you have the skills to manage an indigo house, or . . . a scarlet house! I’ve certainly drooled over some of those boys. How about a little help for a sister in need—”

“—or a big help—”

“Can’t the two of you get your minds out of the gutter for a minute? Wait . . . Phiphi, I think I heard the coins jangling in your purse when you came in—did you have good luck at sparrow tiles last night?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Aha, I knew it! Your face gives everything away; it’s a wonder you can bluff anyone at that game. Listen, if you want Jizan and me to keep our mouths shut in front of your foolish husband about your gaming habit—”

“You featherless pheasant! Don’t you dare tell him!”

“It’s hard for us to think about keeping secrets when we’re so thirsty. How about some of that ‘mind-moisturizer,’ as they say in the folk operas?”

“Oh, you rotten . . . Fine, the drinks are on me.”

“That’s a good sister.”

“It’s just a harmless hobby, but I can’t stand the way he mopes around the house and nags when he thinks I’m going to gamble everything away.”

“You do seem to have Lord Tazu’s favor, I’ll grant you that. But good fortune is better when shared!”

“My parents must not have offered enough incense at the Temple of Tututika before I was born for me to end up with you two as my ‘friends.’ . . .”

Here, inside the Three-Legged Jug, tucked in an out-of-the-way corner of the city, warm rice wine, cold beer, and coconut arrack flowed as freely as the conversation. The fire in the wood-burning stove in the corner crackled and danced, keeping the pub toasty and bathing everything in a warm light. Condensation froze against the glass windows in refined, complex patterns that blurred the view of the outside. Guests sat by threes and fours around low tables in géüpa, relaxed and convivial, enjoying small plates of roasted peanuts dipped in taro sauce that sharpened the taste of alcohol.

Ordinarily, an entertainer in this venue could not expect a cessation in the constant murmur of conversation. But gradually, the buzzing of competing voices died out. For now, at least, there was no distinction between merchants’ stable boys from Wolf’s Paw, scholars’ servant girls from Haan, low-level government clerks sneaking away from the office for the afternoon, laborers resting after a morning’s honest work, shopkeepers taking a break while their spouses watched the store, maids and matrons out for errands and meeting friends — all were just members of an audience enthralled by the storyteller standing at the center of the tavern.

He took a sip of foamy beer, put the mug down, slapped his hands a few times against his long, draping sleeves, and continued:

“. . . the Hegemon unsheathed Na-aroénna then, and King Mocri stepped back to admire the great sword: the soul-taker, the head-remover, the hope- dasher. Even the moon seemed to lose her luster next to the pure glow of this weapon.

“That is a beautiful blade,” said King Mocri, champion of Gan. “It sur- passes other swords as Consort Mira excels all other women.”

The Hegemon looked at Mocri contemptuously, his double-pupils glinting. “Do you praise the weapon because you think I hold an unfair advantage?

Come, let us switch swords, and I have no doubt I will still defeat you.”

“Not at all,” said Mocri. “I praise the weapon because I believe you know a warrior by his weapon of choice. What is better in life than to meet an opponent truly worthy of your skill?”

The Hegemon’s face softened. “I wish you had not rebelled, Mocri. . . .”

In a corner barely illuminated by the glow of the stove, two boys and a girl huddled around a table. Dressed in hempen robes and tunics that were plain but well-made, they appeared to be the children of farmers or perhaps the servants of a well-to-do merchant’s family. The older boy was about twelve, fair-skinned and well proportioned. His eyes were gentle and his dark hair, naturally curly, was tied into a single messy bun at the top of his head. Across the table from him was a girl about a year younger, also fair-skinned and curly-haired— though she wore her hair loose and let the strands cascade around her pretty, round face. The corners of her mouth were curled up in a slight smile as she scanned the room with lively eyes shaped like the body of the graceful dyran, taking in everything with avid interest. Next to her was a younger boy about nine, whose complexion was darker and whose hair was straight and black. The older children sat on either side of him, keeping him penned between the table and the wall. The mischievous glint in his roaming eyes and his constant fidgeting offered a hint as to why. The similarity in the shapes of their features suggested they were siblings.

“Isn’t this great?” whispered the younger boy. “I bet Master Ruthi still thinks we’re imprisoned in our rooms, enduring our punishment.”

“Phyro,” said the older boy, a slight frown on his face, “you know this is only a temporary reprieve. Tonight, we each still have to write three essays about how Kon Fiji’s Morality applies to our misbehavior, how youthful energy must be tempered by education, and how—”

“Shhhh—” the girl said. “I’m trying to hear the storyteller! Don’t lecture, Timu. You already agreed that there’s no difference between playing first and then studying, on the one hand, and studying first and then playing, on the other. It’s called ‘time-shifting.’”

“I’m beginning to think that this ‘time-shifting’ idea of yours would be better called ‘time-wasting,’” said Timu, the older brother. “You and Phyro were wrong to make jokes about Master Kon Fiji—and I should have been more severe with you. You should accept your punishment gracefully.”

“Oh, wait until you find out what Théra and I—mmf—”

The girl had clamped a hand over the younger boy’s mouth.

“Let’s not trouble Timu with too much knowledge, right?” Phyro nodded, and Théra let go.

The young boy wiped his mouth. “Your hand is salty! Ptui!” Then he turned back to Timu, his older brother. “Since you’re so eager to write the essays, Toto-tika, I’m happy to yield my share to you so that you can write six instead of three. Your essays are much more to Master Ruthi’s taste anyway.”

“That’s ridiculous! The only reason I agreed to sneak away with you and Théra is because as the eldest, it’s my responsibility to look after you, and you promised you would take your punishment later—”

“Elder Brother, I’m shocked!” Phyro put on a serious mien that looked like an exact copy of their strict tutor’s when he was about to launch into a scolding lecture. “Is it not written in Sage Kon Fiji’s Tales of Filial Devotion that the younger brother should offer the choicest specimens in a basket of plums to the elder brother as a token of his respect? Is it also not written that an elder brother should try to protect the younger brother from difficult tasks beyond his ability, since it is the duty of the stronger to defend the weaker? The essays are uncrackable nuts to me, but juicy plums to you. I am trying to live as a good Moralist with my offer. I thought you’d be pleased.”

“That is — you cannot —” Timu was not as practiced at this particular subspecies of the art of debate as his younger brother. His face grew red, and he glared at Phyro. “If only you would direct your clever- ness to actual schoolwork.”

“You should be happy that Hudo-tika has done the assigned reading for once,” said Théra, who had been trying to maintain a straight face as the brothers argued. “Now please be quiet, both of you; I want to hear this.”

…slammed Na-aroénna down, and Mocri met it with his ironwood shield, reinforced with cruben scales. It was as if Fithowéo had clashed his spear against Mount Kiji, or if Kana had slammed her fiery fist against the surface of the sea. Better yet, let me chant for you a portrait of that fight:

On this side, the champion of Gan, born and bred on Wolf’s Paw; On that side, the Hegemon of Dara, last scion of Cocru’s marshals.

One is the pride of an island’s spear-wielding multitudes; The other is Fithowéo, the God of War, incarnate.

Will the Doubt-Ender end all doubt as to who is master of Dara?

Or will Goremaw finally meet a blood-meal he cannot swallow? Sword is met with sword, cudgel with shield.

The ground quakes as dual titans leap, smash, clash, and thump. For nine days and nine nights they fought on that desolate hill, And the gods of Dara gathered over the whale’s way to judge the strength of their will. . . .

As he chanted, the storyteller banged a coconut husk against a large kitchen spoon to simulate the sounds of sword clanging against shield; he leapt about, whipping his long sleeves this way and that to conjure the martial dance of legendary heroes in the flickering firelight of the pub. As his voice rose and fell, urgent one moment, languorous the next, the audience was transported to another time and place.

. . . After nine days, both the Hegemon and King Mocri were exhausted. After parrying another strike from the Doubt-Ender, Mocri took a step back and stumbled over a rock. He fell, his shield and sword splayed out to the sides. With one more step, the Hegemon would be able to bash in his skull or lop off his head.

“No!” Phyro couldn’t help himself. Timu and Théra, equally absorbed by the tale, didn’t shush him.

The storyteller nodded appreciatively at the children, and went on.

But the Hegemon stayed where he was and waited until Mocri climbed back up, sword and shield at the ready.

“Why did you not end it just now?” asked Mocri, his breathing labored.

“Because a great man deserves to not have his life end by chance,” said the Hegemon, whose breathing was equally labored. “The world may not be fair, but we must strive to make it so.”

“Hegemon,” said Mocri, “I am both glad and sorry to have met you.” And they rushed at each other again, with lumbering steps and proud hearts. . . .

“Now that is the manner of a real hero,” whispered Phyro, his tone full of admiration and longing. “Hey, Timu and Théra, you’ve actually met the Hegemon, haven’t you?”

“Yes . . . but that was a long time ago,” Timu whispered back. “I don’t really remember much except that he was really tall, and those strange eyes of his looked terribly fierce. I remember wondering how strong he must have been to be able to wield that huge sword on his back.”

“He sounds like a great man,” said Phyro. “Such honor in every action; such grace to his foes. Too bad he and Da could not—”

“Shhhh!” Théra interrupted. “Hudo-tika, not so loud! Do you want everyone here to know who we are?”

Phyro might be a rascal to his older brother, but he respected the authority of his older sister. He lowered his voice. “Sorry. He just seems such a brave man. And Mocri, too. I’ll have to tell Ada-tika all about this hero from her home island. How come Master Ruthi never taught us anything about Mocri?”

“This is just a story,” Théra said. “Fighting nonstop for nine days and nine nights — how can you believe that really happened? Think: The storyteller wasn’t there, how would he know what the Hegemon and Mocri said?” But seeing the disappointment on her little brother’s face, she softened her tone. “If you want to hear real stories about heroes, I’ll tell you later about the time Auntie Soto stopped the Hegemon from hurting Mother and us. I was only three then, but I remember it as though it happened yesterday.”

Phyro’s eyes brightened and he was about to ask for more, but a rough voice broke in.

“I’ve had just about enough of this ridiculous tale, you insolent fraud!”

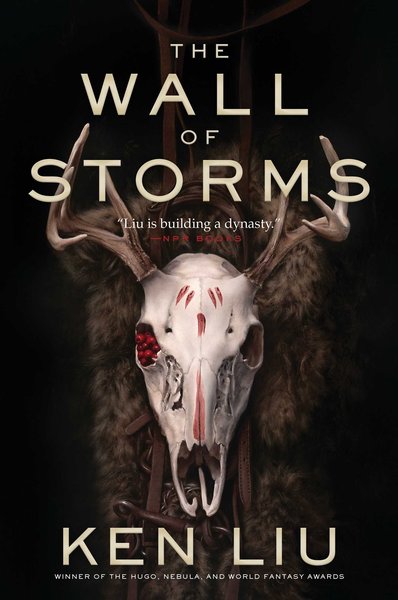

The Wall of Storms,

the second volume in The Dandelion Dynasty

was published October 4, 2016 by Saga Press

Read more about the launch here.

All rights reserved. Available in hardcover and digital editions worldwide.

Ken Liu (kenliu.name) is an author and translator of speculative fiction, as well as a lawyer and programmer. A winner of the Nebula, Hugo, and World Fantasy awards, he has been published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Asimov’s, Analog, Clarkesworld, Lightspeed, and Strange Horizons, among other places.

Ken Liu (kenliu.name) is an author and translator of speculative fiction, as well as a lawyer and programmer. A winner of the Nebula, Hugo, and World Fantasy awards, he has been published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Asimov’s, Analog, Clarkesworld, Lightspeed, and Strange Horizons, among other places.

Ken’s debut novel was The Grace of Kings (2015), the opening novel in The Dandelion Dynasty; the second volume, The Wall of Storms, was released October 4, 2016 by Saga Press. His short story collection The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories was called “Profound enough to hurt” by Amal El-Mohtar of NPR. He lives with his family near Boston, Massachusetts.

Ken is also a noted translator. His acclaimed translation of Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem won the Hugo Award for Best Novel in 2015, the first translated novel to ever receive that honor.

Ken was interviewed for Black Gate by Derek Kunsken in March 2016.