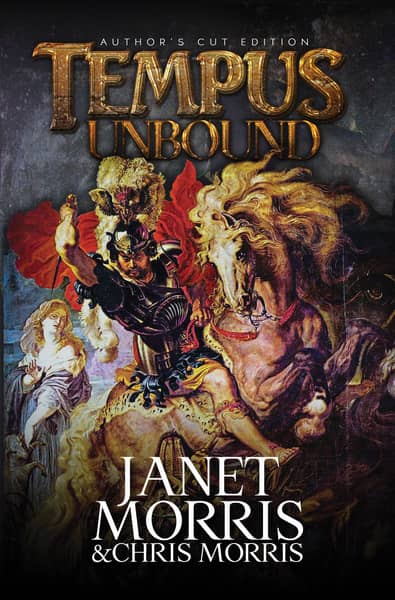

Black Gate Online Fiction: An Excerpt from Tempus Unbound

By Janet Morris and Chris Morris

This is an excerpt from Tempus Unbound, by Janet Morris and Chris Morris, presented by Black Gate magazine.

It appears with the permission of Janet Morris and Chris Morris, and may not be reproduced in whole or in part. All rights reserved. Tempus Unbound is available in hardcover, trade paper; and in Kindle, Nook, and other electronic formats at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, I Tunes and other booksellers.

Chapter 17: Hunters From the Future

Something scrambled among the bushes, and Mano dove after it in the dusk.

Tempus might have let it go, whatever it was: sentry, craven fiend, guard dog or wild hog. Stealth was essential. As the sun buried its face behind tall trees for the night, the citadel came to life: its lights lit, one on a great tower, others down below.

He could smell Cime, even from this distance. And he fancied he could hear her call him, taunts and brash curses in the face of death, all barely out of earshot, so he could hear her tone but not her words.

Thus he paid little attention to Mano, crashing around in the bushes after his prize. If the god’s new avatar couldn’t handle one lurker, then that was between Enlil and Mano, not Tempus’ concern.

Cime was. Here where the god had put him, deposited on a rolling plain dotted with stone walls and fruit trees, he stood certain of confrontation, ready for war. The blood in his veins burned like molten iron. The heart in his breast beat like thunder. The pulse in his ears thumped like the drumbeat pounded a rhythm to march a rank to war or keep galley oarsmen rowing together. His skin clung too tight to him; its every hair stirred in a sorcerous wind. His eyes tingled, drawing color from the night.

He was yet locked in the god’s time-distortion, girded for battle with all his attributes about him, and heedless of his right-hand man because of that.

Tempus had never been more acute, or more alone, than in those moments while his body and mind adjusted to this arena chosen by Enlil and His sorcerous enemy.

So he didn’t notice Mano returning, triumphant, pushing a boy in a chokehold before him, until Mano wrestled the youngster square into Tempus’ path.

“Look what I found.” In the light of a rising moon, Mano’s face was scratched, his breathing ragged.

The boy he held before him couldn’t utter a word: Mano’s elbow under his chin kept his jaws shut. Both his arms were pinned by Mano’s free one, his spine and neck strained to the breaking point.

The wild-eyed youth struggling for breath and freedom wore peasant garb: a rude chiton and sandals. The scabbard on his hip, even in the dark, looked homemade to Tempus’ practiced eye. A sword might once have hung there and been lost, a casualty of his struggle with Mano or some other.

“Be still!” Mano lifted his elbow slightly and the boy went up on tiptoes with a sound between an agonized moan and a defiant groan. “Well, Commander, what do we do with him? We can’t let him go . . .”

“Kill him,” Tempus suggested. to see what the youth would do.

The boy didn’t turn into a viper in Mano’s grasp, nor ooze acid spittle, nor spin inward and disappear with an audible pop. He struggled feebly once again, then slumped against Mano, peering at Tempus with huge and helpless eyes.

Mano’s gruff voice warned, “Easy, kid. Tempus, I can’t do that — he’s only a youngster, skulking around in the bushes with a scrap-metal sword.”

“In these bushes.” Tempus indicated the citadel’s lights. “Let him speak. Then we decide.”

Tempus’ body knew the boy to be no wizard — not a mageling or even a possessed soul. But he wanted to see what the youth might say, and learn why he’d come here now, where everything smelled of fate and nothing, surely, could occur by chance.

The sorcerers must be patrolling their grounds. The god had slipped them past the wizards’ wards. Such wards would be strong. So how had the boy blundered close? And why?

In Tempus’ head, Enlil only rustled. The god watched with intense interest. And Tempus nursed a suspicion as to the nature of Mano’s prisoner. He did not like what he suspected.

Here, in this place, neither he nor Mano were native. But this boy was . . . And Enlil had a hunger for avatars this season.

Beyond in the starlit night, something whined, keened, and chittered; a scavenger bayed at the moon.

The boy shivered. Mano took his elbow away, holding the youth with one hand in his hair and the other round his chest.

“Speak up, kid. What are you doing here?” Mano demanded.

“I . . .” Teeth chattered. “I didn’t.” Tongue twisted. The young face, barely able to raise a beard, shone with sweat in a shaft of moonlight from beyond the trees. The youth trembled in fits. “I’m . . . Look — I’m just a kid, like you say. Playing a game, that’s all. My character’s supposed to find a magic talisman and then go to the castle . . .” Desperation broke the voice into shards of misery. “I don’t know who you guys are, or what this is all about. I’m sorry. Let me go, okay? I’ll go on my way. I won’t tell anybody about this . . .”

“Magic?” Tempus bore down on the youngster. “Castle?”

“Oh, shit,” muttered the boy again writhing in Mano’s grasp.

Over his prisoner’s head, Mano looked at Tempus and pulled hard on the hank of hair he held.

Tempus needed no weapon to deal with such a youth. He took the boy’s chin in his fingers, letting his thumb press painfully into the soft spot there. “Tell us about the magic, and about the castle.”

“L –L – look,” the youth said when he could gulp a breath. “My name’s Jerry, and I’m out here playing a fantasy game. I thought . . . I mean, your outfits. I thought you were part of the group . . .” His chest began heaving.

Mano kicked the boy’s legs out from under him and brought him down to the ground so he could vomit into the grass, instead of onto Mano himself and himself.

“Tempus,” said his right-hand man as the boy wretched like a drunkard, “what do you think?”

“Bring him,” Tempus said and started toward the castle.

“Shit is right,” he heard Mano mutter, then roughly tell the boy what would happen to him if he made an outcry or tried to run.

When Mano caught up with Tempus, he had the boy’s wrists trussed behind his back with the makeshift swordbelt, and his other hand firmly in the youth’s long hair.

The boy’s teeth were chattering. “Honest, you guys, it was only a game. It’s not really a castle. It’s a farmhouse. And I don’t understand the lights, either. The bank foreclosed that place last month. It’s abandoned. You gotta listen to me — there’s no magic, no magicians, no anything. It’s just a game, a scenario we made up. Somebody buried something out here, a pretend talisman, for me to find . . .”

“It’s no game, Jerry,” Mano told him. “Now tell us the truth, or I’ll take Tempus’ advice and gut you here and now.”

Tempus spoke sharply Mano in the Lemurian tongue: “Wrong, Mano. A game it is: the god’s game.”

Transiently, rage at Enlil filled him. Why thrust this youngster upon him at the worst possible time? The god, however, ignored him. Enlil wanted a third soul for his own, a native of this land. And the god had found one. Tempus deemed the choice unacceptable. To take the first available believer, even were it a downy-cheeked youth, seemed unfair.

This boy was too young, an innocent perhaps, and frail of spirit. No peasant with a homemade scabbard would prove a fit fighter for this battle. Nevertheless, the god looked fondly upon the youth: Tempus could feel supernal lips being licked, a dour amusement welling up inside him. The god wanted this games-player for his own, because in the youngster lay belief and a longing for all the terrible attributes of the god-bound.

Perchance, with Mano on his right, a child might not be the worst adherent. But Tempus had no time to test this youth called Jerry.

So he said, “Jerry, real magic lurks here. A real battle in the offing.” He drew the knife from his belt, flipped it, and held it out hilt-first to Mano. “Cut him loose. If he runs, so be it. If not, he’s ours.”

The boy whined, “Somebody tell me what’s going on?” as Mano cut him free.

Jerry stood still when he could have run, limned by the silver moonlight, tugging on his chiton. His lips blanched pale, but he held his head high.

Tempus said, “The magic you sought has found you. So has the god of storm, of war and sack and pillage. He is the god of the armies, and you pretend to be a fighter. Are you, really?”

“I — Whew, if I find out who put you two up to doing this . . . Okay, I’m in. Take me to the battle, men. I ought to tell you about my character ―”

Mano looked at Tempus; Tempus shook his head. “Give the boy my knife.” Enlil was adamant. The knife knew sorcery and thirsted for it. Already its blade glowed pink.

“Damn,” said the youngster. “I’m Stinger — ”

The boy had a war-name. Tempus relaxed a bit. Perhaps the god had made a canny choice. “The knife is yours, if you survive the test. Be warned, Jerry called Stinger: It will find sorcerers, and it knows its enemies.”

“Test?” said the youth.

“Tempus,” said Mano, “let’s tie him to a tree and get on with this.”

“Give him one seed. And give him the benefit of the doubt. You and I will fight here and depart. This one will stay, and a part of Enlil will stay with him.”

“Commander,” Mano began to argue, “let’s think about this. We don’t know this kid. He can’t do anything but cause trouble.”

“He can die here,” Tempus said. “I won’t tie him to a tree with sorcery about to run rampant. And Enlil is choosing His avatars, not I. Give him the knife. And one seed,” Tempus repeated, implacable, his voice so thick with regret that it came out of him as a growl. Perhaps if Rath had survived, Enlil would not have needed this boy-child. But Rath had not survived.

“Your knife. Right. Sir.” Full of rebellion and disbelief, Mano handed the knife to the youngster.

The boy said. “Wow!” He held up the knife to catch the moonlight on its blade. “No kidding, man? I can keep this if — ?”

“Man-o,” Tempus corrected. “And some call me the Riddler, Stinger. Forthwith you will lead us as silently and stealthily as you can to the great citadel’s tower.” He pointed.

“To the barn?” Jerry called Stinger wanted to know.

“Yeah.” Mano sighed. “To the barn. Then take your new knife and get the hell out while you still can, kid. You don’t realize it yet, but you just walked into your worst nightmare.”

“Do as your heart dictates,” Tempus advised. “Listen to the god who speaks from inside you, for you will be Lord Storm’s eyes and ears in this place long after we are gone.”

Stinger looked up at him and said, “Damn. We’re going to save the lady taken prisoner by the magicians, right? That’s the game I’m in . . .”

“Now, if you please,” Mano prompted.

“That is the game we all are in,” Tempus told Stinger, wishing the god would stick to men and leave boys be. The youth tore his shining eyes from Tempus and, with one last glare at Mano, strode away, uncertain, self-conscious, but determined. He rubbed his arms. He turned to make sure they were coming. He crept through the bushes, the god’s knife in his hand.

And the two of them followed.

Chapter Eighteen: Citadel of Corn

“What do you call this land?” Tempus asked Stinger when the boy, crouched low, motioned them to halt behind a great haystack crowned with a tarp.

“‘Land?’ Stinger’s eye-whites glowed with reflected moonlight.

“State,” Mano clarified, from Tempus’ right. “We’re not in New York . . .”

“Kansas,” said the youth wonderingly. “Greenfield, Kansas.”

“I should have known,” Mano said on a chuckle that made no sense to Tempus. “And the year?”

“The year? You guys are carrying this way too far. But okay . . .” Jerry called Stinger gave a date.

Mano nodded and whistled, rueful. “Venue Three.”

“The same country we left?” Tempus asked.

“Same. Within a week after we left it. That god of yours is earning my respect.”

“He’s your god, after what happened,” Tempus reminded Mano. “And offer your respect freely, or He’ll teach you lessons no man likes to learn.”

“Like what?” Mano said, challenge in his tone, and frustration.

They were watching the barn for some sign of activity, waiting for something to come or something to go. Beyond was a house and in it were lights aplenty. Itwas made of stone and Tempus could feel the cold of that stone even from this distance.

“Lessons, that’s all,” said Tempus. Mano didn’t yet realize what being the god’s avatar meant. Tempus was beginning to feel guilty about Mano; the inclusion of Stinger in their party had brought the hungry god to full attention.

And the boy looked between them wordlessly, trembling with adventure and his first taste of manhood.

Tempus said then what he’d hoped not to have to say, would not have said if the youngster wasn’t present: “The god took you up, Mano. You slew sorcerers in His name. You’ve drunk the sap of the tree and flung the seeds of destruction into His enemies. You’ll not die with your contemporaries; you’ll fight these wizards until they or you are no more. I knew it when the god made you bow before him. You must have known it when the fiends attacked.”

“Fiends?” Stinger whispered.

Mano ignored the youth. “Tempus, just because we got lucky — ”

“Mano, I am older than your civilization. Do I look decrepit to you? You’ve fought by my side. Do I seem some maundering oldster? Have I ever told you aught but the truth?”

“No.” Mano looked down, at his black thunderwand with its red button.

“You heed me, too, Stinger. You say you play at killing magicians. Thus you’ve made the god think you long to be a warrior. So warrior you’ll be; and if you live till tomorrow, you’ll be one until this war is done. What say you, son? Take your leave now, go back to your game, or stay and fight.”

“No way I’m leavin’,” Stinger breathed.

In Tempus’ head, Enlil let out a mighty roar that made his teeth water, furious that Tempus would try to dissuade the newly-chosen representative of His power.

But either Enlil had already claimed the boy, or the boy came foredoomed by fate, for Stinger added, “All my life, I’ve wished something like this would happen. And it couldn’t. At least I thought it couldn’t. But now, whatever this is, it seems like it’s real. If your god wants me, Mister Tempus, and that means I can . . . help, then he can have me.”

Tempus squeezed his eyes shut. In his head, Enlil laughed uproariously, saying, See, insolent avatar? Old fool, it is the youth of your breed who sustain Me. Feel your regrets, ancient servant, but know they haunt thineself alone. The young mortal wishes immortality. He wishes power in his right arm and an enemy worth fighting. You wish peace for those who fear only inconsequence. We will put you out to pasture, old warhorse, Me and Mine.

Tempus remembered his soldiers, every one, in that instant: a parade of eager faces became bloody faces, then faces swollen black in death. And Tempus conceded that in the young lurked no lack of lethality, only of comprehension.

The fighters he loved had all died or been lost to him in time and space. He could not empathize with a boy who’d seen so few seasons, or hope to understand what went through so alien a mind as Stinger’s. But he knew young fighters; and he knew that, to the young, anything was better than nothing: war in a cause was better than a life of peaceful drudgery. They all wanted something to believe in, a consecrated enemy, a head to lop in one stroke that would change their lives.

The true war raged within each soul, but they never learned until they came face to face with Death and took a life, or lost their own. No words would turn this child from his path, when Enlil wanted him for a servant. Better to turn Mano away, and with more reason. Tempus wondered at what a poor world this must be, if the best the god could find for an avatar was a youngster barely shaving.

But such had been the way of it for thousands of years, and it would be this way forever. Tempus missed his Sacred Band then, all his seasoned fighters, so hard with battle that none had any questions left, nor aught to save but pride.

Stinger’s eyes, full of excitement, met his. He was honored; he was at Tempus’ service.

Hero-worship dripped from lips never split in mortal combat or burned with acid spittle from a demon’s mouth. Tempus didn’t listen to the youngster’s chatter. He said, “Quiet, Jerry called Stinger. Save it for the enemy.”

And Mano said, “Send the kid around the back.”

Tempus understood the deeper message. “Stinger, circle the barn. Make certain you’re not seen. If you see a woman, or any . . . unusual manifestations . . . come back and tell us. Should you be discovered, use the knife if you can. The seed makes a great explosion, a hundred heartbeats after release from its pod. Do not use cast the seed unless you can find shelter from the explosion to follow. Now, go.”

Just like that. No more warning. No soldier’s honorific, no ritual farewell. This child was not one of his, this was one of the god’s. The god must take care of Stinger, whose true name was Jerry. Tempus had neither the time nor the heart for another boy.

Mano was more than boy enough.

“Right, Commander,” said the quick youth, who’d heard Mano call Tempus thus. And he scuttled off, leaving Mano and Tempus alone.

“This sucks,” Mano said before Tempus could speak.

“It’s the god, not I. That youth is the god’s recruit, not yours; not mine. Perhaps we need him.”

“He’ll be dead by morning.”

“I doubt it. Death is a blessing that avatars seldom receive. Keep in mind, for your soul’s sake, that you are not as mortal as once you were.”

Those words spoke clear enough.

Mano made a derisive noise, then looked at him very closely. “You’re serious, aren’t you, about all of this?”

“Would that I were not. Try not to fall alive into the hands of sorcerers, Mano. You know too many of your world’s secrets.”

“Commander . . . Can I still . . . kill myself, if worse comes to worst?” Mano asked, very low.

“I cannot say,” Tempus admitted. “You might put it to the god, if the need arises. But I’ve suffered until He has deigned to remove my flesh from plights where death would have been a blessing.”

“Can’t you . . . quit?”

“Quit living? Quit breathing? I don’t know how,” Tempus replied. “Nor do you, so leave pretense aside. Call for help when you need it. Demand your due from heaven. And eradicate the enemy, wherever you can find him.”

“So you’re saying, do the job in front of me and let the god take care of my mortal butt?”

“That is exactly what I’m saying.”

“Can we lose the kid, shake him off, leave him behind?”

“I say again: He is not ours. He belongs to Lord Storm. He shall do for his time what you will do for yours.”

“And you — ? What will you do, when this is over?”

“Find Sandia.” The words slipped out of him unbidden.

“You’re a cocky son of a bitch,” Mano muttered. “You’re so sure that you’ll come through it?”

“My horse is in Lemuria. My heart is there, also. Enlil keeps his bargains. If I don’t see you once the battle is done, remember what I’ve told you. You tend your war, Mano, and teach the god’s way. Someday, the world won’t need sacrifices such as we. Now, it does.”

“In order to survive? I don’t understand any of this.”

“Yes, you do, rightman. But you do not like it.”

And that was true enough.

They stayed where they were until the boy came around the barn, scuttling back toward them like a creature born of the night.

Tempus could see the pink and blue glow of magic and antimagic surrounding Stinger. Perhaps Mano saw it too, for the fighter from the future rubbed his eyes.

The boy said, “There’s nothing in the barn but corn,” as if he knew it for a certainty.

“Then we go to the house,” Tempus said, and added: “Stinger, you first. Reconnoiter and bring back word to us.”

The god in his head was sure of what to do: wait, and let their presence draw the enemy and the confrontation to them.

He sat on his haunches then, feeling the yield in the earth. With a rattling sigh he told Mano “If the barn is filled with corn, go get some, bring it here. Then we’ll eat and rest until the time is upon us.

“Jesus, you want to eat?”

“I want to violate the sorcerers’ place and sup on their sustenance, yes. I want to bring them here, to me, where the god has chosen the battlefield. And I want to sit, and rest, and wait, and consider the way the wind blows and the chill of the night. What else? What do you do before a battle?”

Mano, ducking his head, said, “Ah, we don’t fight battles like this. And then he raised it. “I guess that’s not true. I’m always antsy before action. I’ll get the corn.”

And off he went.

Tempus watched with sadness as Mano skulked toward the barn, then made a second full circuit of it before he found a door he could open, and slipped inside. The god wanted his fighters committed, each on his own, each alone with his destiny and fully prepared by ritual. Thus, the circuit of the barn, which the Ravener had decreed.

The sorcerers would bring this battle to them, of this the god was certain.

Tempus knew the god and knew the way that men were tested and how such confrontations were begun. And he could smell his sister, still — her musk, her pain, her acrid sweat yet tickled his nostrils. Eating of the sorcerers’ bounty might not be strictly necessary, but he liked the fitness of it.

As for what was necessary, that hoary ritual involved circuiting the barn and the house, crossing the wards and making introductions by those means. When he was ready, he’d go himself, do it himself.

But he was not yet ready. He waited for the sun to rise. He wanted the one called Stinger to find time to make peace with himself — and be alone with the god. And he wanted Mano to learn to listen to his heart.

But Tempus knew that seldom in life does a man get what he wants.

No sooner had Mano opened the door to the barn and slipped inside than a bright light began to glow through the door’s cracks and the siding’s planks.

The light, so bright and unholy, forced Tempus to shade his eyes and look away.

He knew the fighter from the future would use the seed he carried, as he knew that the god went inside the barn with the fighter, among the corn and the magic there.

Asudden, Tempus might as well have been bicorporal: he could see through Mano’s eyes as all the corn became whorls of fire; see as that fire attacked his right-hand man, who had only the god’s seeds and his thunderwand to protect him.

Between Mano and Enlil on the one hand, and the sorcerers on the other, the fate of a world hung, a contested fabric of reality spun from dark and bright.

Enlil held Tempus back with all the power that the Storm God could command.

When the barn flared with a light brighter than the sun, Tempus could no longer see what Mano saw . . . if Mano still saw anything at all.

The light burst around the boards of the barn and ate them. It crawled up the citadel’s tower and spurted out its top. As it consumed the corn, a great wave of superheated air hit Tempus broadside, tossing him through that air as if he weighed no more than a leaf.

When he came to rest on solid ground, the place where the barn had been existed only as a raging conflagration whose heat no man could survive.

Stinger came running toward him, yelling unintelligibly. Behind the youngster, the stone house flared, illuminated as bright as day, every crack and chunk of mortar showing.

Within that house, lights were ablaze and shapes peered out the windows.

“Where’s Mano?” Stinger yelled. “What’s happening?”

“The fight’s begun,” Tempus bellowed back, over the roaring of the inferno behind him, drawing his blade as he jogged toward the youth.

“But Mano —”

“Back there,” Tempus said, grabbing for the boy who seemed about to hurtle past him. His grip on Stinger’s shoulder brought the youth to a halt and nearly jerked him off his feet.

“Back there? In the barn?” Stinger shouted, squinting into Tempus’ eyes, his face blackened with soot and grime. “Nothing could live through that . . .”

“This is the game, Jerry called Stinger. Play it for your life, and don’t worry about a man the god has called.”

“But what if he’s hurt in there — ?”

“We cannot help him. We help ourselves. The lord of sack and storm sees to his own. Now, how many did you count in the house?” As he asked the question, Tempus pushed the boy roughly away from the barn, toward the house where the sorcerers had manifested.

“Ah — maybe five guys, a woman, and a bunch of . . . things. It seemed like they were coming out of the woodwork . . .”

“Once the barn went up, yes. They had to get out fast.”

Stinger was pacing him, but reluctantly. The firelight danced on his face, lending it a masklike, frozen look. His eyes were round with fear and excitement. He stumbled, trying to jog backward, still fascinated by the blaze. Then he looked around, at where they were headed.

“We’re going in there? Into that house? Just the two of us?”

“Perhaps. Perhaps they’ll come out, who knows?”

“What about Mano?”This time, the question rode tortured yelp ripped from the youth’s throat.

“You don’t know Mano. You don’t know me. You know only yourself and your fear. Cut and run, if you can. Otherwise, come along.”

Tempus picked up his pace, leaving the boy to fight through his grief and fear on his own.

For an instant Cime stood waiting, proving that the first round had gone to Tempus’ little force. Then she disappeared.

Wherever Mano was, Tempus hoped the god would let him know that he’d won his part of the battle.

As for the youth called Stinger, only the god knew what the boy was for. Tempus headed straight for the front door, where raised steps led to a porch.

In the front windows of the house, he could see dark shapes watching him come. And some of those shapes were not even vaguely human.

From behind, he heard Stinger calling breathlessly, “Wait up, damn it. Wait for me!”

Janet Morris alone and Janet Morris and Chris Morris jointly have authored six previous novels and two novelized anthology volumes in their Sacred Band of Stepsons series. Some earlier books in this series were originally published as Science Fiction Book Club selections, Baen hardcover, Ace and Baen mass market editions, and later reissued in definitive, expanded trade paper and electronic “Authors’ Cut” editions by Paradise Publishing, Kerlak, and Perseid Press.

Janet Morris alone and Janet Morris and Chris Morris jointly have authored six previous novels and two novelized anthology volumes in their Sacred Band of Stepsons series. Some earlier books in this series were originally published as Science Fiction Book Club selections, Baen hardcover, Ace and Baen mass market editions, and later reissued in definitive, expanded trade paper and electronic “Authors’ Cut” editions by Paradise Publishing, Kerlak, and Perseid Press.

Some works in this series were previously published in somewhat different form in the Thieves World® shared universe or as authorized works taking place beyond Sanctuary®.

Janet E. Morris began writing in 1976 and has since published more than 20 novels, many co-authored with her husband Chris Morris or others such as David Drake and C.J. Cherryh. She now owns the copyrights to more than 60 novels, both fiction and non-fiction. Janet’s first novel, published in 1977, was High Couch of Silistra, the first in a quartet of novels with a very strong female protagonist. Since then she has contributed short fiction to the shared universe fantasy series Thieves World, in which she created the Sacred Band of Stepsons, a mythical unit of ancient fighters modeled on the Sacred Band of Thebes.

She also created, orchestrates, edits, and writes for the continuing, award-winning Bangsian fantasy series Heroes in Hell. Eighteen volumes have been published since 1986, the latest being Dreamers in Hell, Poets in Hell, and Doctors in Hell.

Most of her fiction work has been in the fantasy and science fiction genres, although she has also written historical and other novels. Her 1983 book I, The Sun, a detailed biographical novel about the Hittite King Suppiluliuma I, was praised for its historical accuracy, and has recently been reprinted by Perseid Press. Among Janet’s numerous novels are the Kerrion Empire Trilogy, Warlord, Threshold (with Chris Morris), and The Sacred Band.