A Storm of Another Kind: Mother of Storms by John Barnes

|

|

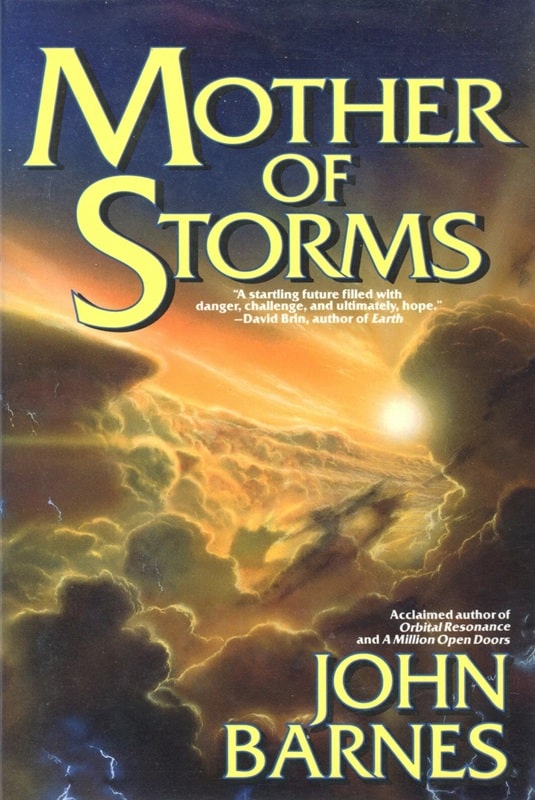

Mother of Storms (Tor Books, July 1994). Cover by Bob Eggleton

One of science fiction’s subgenres is that novel that emulates the style of bestsellers — bestsellers as they were before the fantastic genres became a big part of the cultural mainstream. Michael Crichton, for one, specialized in this type of writing, from The Andromeda Strain to Jurassic Park; but other writers take it up from time to time: Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle in Lucifer’s Hammer, David Brin in Earth, and much more recently Andy Weir in The Martian and Harry Turtledove in Supervolcano.

Some markers are common in this sort of book: reduced use of expository passages, a more demotic prose style, a near future setting that’s easy to imagine, multiple viewpoints and a large cast of characters — and despite this, a much reduced presence of characters who have a detached, scientific view of the world. John Barnes’s Mother of Storms is a classic example of that kind of science fiction.