So We Were In This Bar . . .

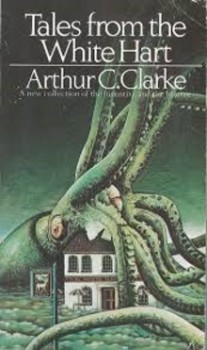

There’s a long tradition in western literature of the “framing device” – think Chaucer and The Canterbury Tales … or the Thousand Nights and a Night if we want something more obviously in our genre. Or Asimov and his Black Widower Mysteries.

There’s a long tradition in western literature of the “framing device” – think Chaucer and The Canterbury Tales … or the Thousand Nights and a Night if we want something more obviously in our genre. Or Asimov and his Black Widower Mysteries.

My personal favourite among short story framing devices, however, is the bar story -– and I don’t mean the kind that starts, “We were in this bar…” Though, come to think of it, that’s how all my vacation stories start. Hmmm.

The device itself is fairly straightforward. The bar is a gathering place of disparate, but like-minded, people who exchange stories and anecdotes, usually involving people not present at the time. Sometimes the patrons of the bar take turns telling tales and sometimes, as with PG Wodehouse’s collections Meet Mr. Mulliner and Mr. Mulliner Speaks, one person in particular is the storyteller.

Undoubtedly because the storytellers are in a bar, the stories themselves can get a bit far-fetched, leading to such well-known formats as the Shaggy Dog Story and even the Tall Tale itself.

Which seems tailor-made for SF and Fantasy stories, don’t you think?